Jain literature

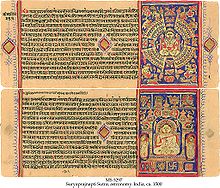

The oldest surviving material is contained in the canonical Jain Agamas, which are written in Ardhamagadhi, a Prakrit (Middle-Indo Aryan) language.

Jains believe their religion is eternal, and the teachings of the first tīrthaṅkara, Ṛṣabhanātha, existed millions of years ago.

[1] It states that the tīrthaṅkaras taught in divine preaching halls called samavasarana and were heard by gods, ascetics, and laypersons.

[3] The spoken scriptural language is believed to be Magadhi Prakrit by Śvetāmbara Jains, and a form of divine sound or sonic resonance by Digambaras.

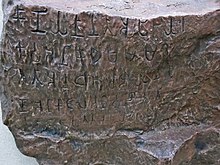

[1][4] Initially, the canonical scriptures were transmitted through an oral tradition and consisted of teachings of historical Jain leaders like Mahavira codified into various collections.

[6] Gautama and other Gandhars (the chief disciples of Mahavira) are said to have compiled the original sacred scriptures which were divided into twelve Angas or parts.

[12]Elsewhere, Bronkhorst states that the Sūtrakṛtāṅga "dates from the 2nd century BCE at the very earliest," based on how it references the Buddhist theory of momentariness, which is a later scholastic development.

At this time, a long famine caused a crisis in the community, who found it difficult to keep the entire Jain canon committed to memory.

Bhadrabahu decided to travel south to Karnataka with his adherents[13] and Sthulabhadra, another Jain leader remained behind.

[15] The Śvētāmbara order considers these Jain Agamas as canonical works and sees them as being based on an authentic oral tradition.

"sky-clad", i.e. naked) order, which hold that Āchārya Bhutabali (1st century CE) was the last ascetic who had partial knowledge of the original canon.

The Śvētāmbaras recompiled the Agamas and recorded them as written manuscripts under the leadership of Acharya Shraman Devardhigani along with other 500 Jain scholars.

[25] The canons (Siddhāntha) of the Śvētāmbaras are generally composed of the following texts:[23][26] To reach the number 45, Mūrtipūjak Śvētāmbara canons contain a "Miscellaneous" collection of supplementary texts, called the Paiṇṇaya suttas (Sanskrit: Prakīrnaka sūtras, "Miscellaneous").

According to Winternitz, after the 8th century or so, Svetambara Jain writers, who had previously worked in Prakrit, began to use Sanskrit.

Siddha-Hem-Shabdanushasana by Acharya Hemachandra (c. 12th century CE) is considered by F. Kielhorn as the best grammar work of the Indian middle age.

[citation needed] Jaina narrative literature mainly contains stories about sixty-three prominent figures known as Salakapurusa, and people who were related to them.

[citation needed] The first autobiography in the ancestor of Hindi, Braj Bhasha, is called Ardhakathānaka and was written by a Jain, Banarasidasa, an ardent follower of Acarya Kundakunda who lived in Agra.

Many classical texts are in Sanskrit (Tattvartha Sutra, Puranas, Kosh, Sravakacara, mathematics, Nighantus etc.).

[citation needed] Jain literature was written in Apabhraṃśa (Kahas, rasas, and grammars), Standard Hindi (Chhahadhala, Moksh Marg Prakashak, and others), Tamil (Nālaṭiyār, Civaka Cintamani, Valayapathi, and others), and Kannada (Vaddaradhane and various other texts).

For example, it is generally accepted now that the Jain nun Kanti inserted a 445-verse poem into Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi in the 12th century.

[54] The Digambara Jain texts in Karnataka are unusual in having been written under the patronage of kings and regional aristocrats.

They describe warrior violence and martial valor as equivalent to a "fully committed Jain ascetic", setting aside Jainism's absolute non-violence.

[58] The largest and most valuable libraries are found in the Thar Desert, hidden in the underground vaults of Jain temples.

Both also believe that the 12th Agama Drishtivaad (Dṛṣṭivāda) was lost over a period of time and realised the need to turn the oral tradition to written.