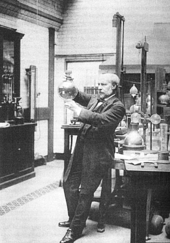

James Dewar

[4] He became a member of the Royal Institution and later, in 1877, replaced Dr John Hall Gladstone in the role of Fullerian Professor of Chemistry.

Dewar was also the President of the Chemical Society in 1897 and the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1902, as well as serving on the Royal Commission established to examine London's water supply from 1893 to 1894 and the Committee on Explosives.

With Professor J. G. McKendrick, of the University of Glasgow, he investigated the physiological action of light and examined the changes that take place in the electrical condition of the retina under its influence.

[7] His interest in this branch of physics and chemistry dates back at least as far as 1874, when he discussed the "Latent Heat of Liquid Gases" before the British Association.

Six years later, again at the Royal Institution, he described the researches of Zygmunt Florenty Wróblewski and Karol Olszewski, and illustrated for the first time in public the liquefaction of oxygen and air.

The vacuum flask was so efficient at keeping heat out, it was found possible to preserve the liquids for comparatively long periods, making an examination of their optical properties possible.

Dewar did not profit from the widespread adoption of his vacuum flask – he lost a court case against Thermos concerning the patent for his invention.

[8] He next experimented with a high-pressure hydrogen jet by which low temperatures were realised through the Joule–Thomson effect, and the successful results he obtained led him to build at the Royal Institution a large regenerative cooling refrigerating machine.

[8] In 1905, he began to investigate the gas-absorbing powers of charcoal when cooled to low temperatures and applied his research to the creation of high vacuum, which was used for further experiments in atomic physics.

Dewar continued his research work into the properties of elements at low temperatures, specifically low-temperature calorimetry, until the outbreak of World War I.

His research during and after the war mainly involved investigating surface tension in soap bubbles, rather than further work into the properties of matter at low temperatures.

[11] In 1899, he became the first recipient of the Hodgkins gold medal of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, for his contributions to knowledge of the nature and properties of atmospheric air.