James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick (20 October 1891 – 24 July 1974) was an English physicist who received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1935 for his discovery of the neutron.

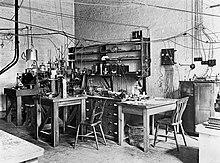

He was Rutherford's assistant director of research at the Cavendish Laboratory for over a decade at a time when it was one of the world's foremost centres for the study of physics, attracting students like John Cockcroft, Norman Feather, and Mark Oliphant.

The physics department was headed by Ernest Rutherford, who assigned research projects to final-year students, and he instructed Chadwick to devise a means of comparing the amount of radioactive energy of two different sources.

[16][17] He was released after the Armistice with Germany came into effect in November 1918, and returned to his parents' home in Manchester, where he wrote up his findings over the previous four years for the 1851 Exhibition commissioners.

The major drawback with it was that it detected alpha, beta and gamma radiation, and radium, which the Cavendish laboratory normally used in its experiments, emitted all three, and was therefore unsuitable for what Chadwick had in mind.

[26][27] In Germany, Walther Bothe and his student Herbert Becker had used polonium to bombard beryllium with alpha particles, producing an unusual form of radiation.

Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie had succeeded in knocking protons from paraffin wax using polonium and beryllium as a source for what they thought was gamma radiation.

[33][34] The theoretical physicists Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg considered whether the neutron could be a fundamental nuclear particle like the proton and electron, rather than a proton–electron pair.

By bombarding boron with alpha particles, Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie obtained a large value for the mass of a neutron, but Ernest Lawrence's team at the University of California produced a small one.

[40] Then Maurice Goldhaber, a refugee from Nazi Germany and a graduate student at the Cavendish Laboratory, suggested to Chadwick that deuterons could be photodisintegrated by the 2.6 MeV gamma rays of 208Tl (then known as thorium C"): An accurate value for the mass of the neutron could be determined from this process.

[50][51] Frederick Reines and Clyde Cowan would confirm the neutrino on 14 June 1956 by placing a detector within a large antineutrino flux from a nearby nuclear reactor.

At the same time, Lawrence's recent invention, the cyclotron, promised to revolutionise experimental nuclear physics, and Chadwick felt that the Cavendish laboratory would fall behind unless it also acquired one.

When Lawrence postulated the existence of a new and hitherto unknown particle that he claimed was a possible source of limitless energy at the Solvay Conference in 1933, Chadwick responded that the results were more likely attributable to contamination of the equipment.

[55][56][57][58] In March 1935, Chadwick received an offer of the Lyon Jones Chair of physics at the University of Liverpool, in his wife's home town, to succeed Lionel Wilberforce.

[62] To build his cyclotron, Chadwick brought in two young experts, Bernard Kinsey and Harold Walke, who had worked with Lawrence at the University of California.

Chadwick was automatically a committee member of both faculties, and in 1938 he was appointed to a commission headed by Lord Derby to investigate the arrangements for cancer treatment in Liverpool.

He surprised everyone by earning the almost-complete trust of project director Leslie R. Groves, Jr. For his efforts, Chadwick received a knighthood in the New Year Honours on 1 January 1945.

In Germany, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann bombarded uranium with neutrons, and noted that barium, a lighter element, was among the products produced.

[71] In a paper co-authored with the American physicist John Wheeler, Bohr theorised that fission was more likely to occur in the uranium-235 isotope, which made up only 0.7 per cent of natural uranium.

When he reached Liverpool, Chadwick found Joseph Rotblat, a Polish post-doctoral fellow who had come to work with the cyclotron, was now destitute, as he was cut off from funds from Poland.

[74] In October 1939, Chadwick received a letter from Sir Edward Appleton, the Secretary of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, asking for his opinion on the feasibility of an atom bomb.

Instead of looking at unenriched uranium oxide, they considered what would happen to a sphere of pure uranium-235, and found that not only could a chain reaction occur, but that it might require as little as 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) of uranium-235, and unleash the energy of tons of dynamite.

It was chaired by Sir George Thomson and its original membership included Chadwick, along with Mark Oliphant, John Cockcroft and Philip Moon.

[80] In July 1941, Chadwick was chosen to write the final draft of the MAUD Report, which, when presented by Vannevar Bush to President Franklin D. Roosevelt in October 1941, inspired the U.S. government to pour millions of dollars into the pursuit of an atom bomb.

In September 1943, the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, and President Roosevelt negotiated the Quebec Agreement, which reinstated cooperation between Britain, the United States and Canada.

Chadwick, Oliphant, Peierls and Simon were summoned to the United States by the director of Tube Alloys, Sir Wallace Akers, to work with the Manhattan Project.

[91] Leaving Rotblat in charge in Liverpool, Chadwick began a tour of the Manhattan Project facilities in November 1943, except for the Hanford Site where plutonium was produced, which he was not allowed to see.

Observing the work on the K-25 gaseous diffusion facility at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Chadwick realised how wrong he had been about building the plant in wartime Britain.

Requests from Groves via Chadwick for particular scientists tended to be met with an immediate rejection by the company, ministry or university currently employing them, only to be overcome by the overriding priority accorded to Tube Alloys.

[106] At this time, Sir James Mountford, the Vice Chancellor of the University of Liverpool, wrote in his diary "he had never seen a man 'so physically, mentally and spiritually tired" as Chadwick, for he "had plumbed such depths of moral decision as more fortunate men are never called upon even to peer into ... [and suffered] ... almost insupportable agonies of responsibility arising from his scientific work'.