Thomas Hunt Morgan

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945)[2] was an American evolutionary biologist, geneticist, embryologist, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries elucidating the role that the chromosome plays in heredity.

In his famous Fly Room at Columbia University's Schermerhorn Hall, Morgan demonstrated that genes are carried on chromosomes and are the mechanical basis of heredity.

Through his mother, he was the great-grandson of Francis Scott Key, the author of the "Star Spangled Banner", and John Eager Howard, governor and senator from Maryland.

[5] Following a summer at the Marine Biology School in Annisquam, Massachusetts, Morgan began graduate studies in zoology at the recently founded Johns Hopkins University.

After two years of experimental work with morphologist William Keith Brooks and writing several publications, Morgan was eligible to receive a Master of Science from the State College of Kentucky in 1888.

[citation needed] The college offered Morgan a full professorship; however, he chose to stay at Johns Hopkins and was awarded a relatively large fellowship to help him fund his studies.

[citation needed] Under Brooks, Morgan completed his thesis work on the embryology of sea spiders—collected during the summers of 1889 and 1890 at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts—to determine their phylogenetic relationship with other arthropods.

[6] Every summer from 1910 to 1925, Morgan and his colleagues at the famous Fly Room at Columbia University moved their research program to the Marine Biological Laboratory.

[7] In 1890, Morgan was appointed associate professor (and head of the biology department) at Johns Hopkins' sister school Bryn Mawr College, replacing his colleague Edmund Beecher Wilson.

Morgan changed his work from traditional, largely descriptive morphology to experimental embryology that sought physical and chemical explanations for organismal development.

Following Wilhelm Roux's mosaic theory of development, some believed that hereditary material was divided among embryonic cells, which were predestined to form particular parts of a mature organism.

Morgan was in the latter camp; his work with Driesch demonstrated that blastomeres isolated from sea urchin and ctenophore eggs could develop into complete larvae, contrary to the predictions (and experimental evidence) of Roux's supporters.

[11] A related debate involved the role of epigenetic and environmental factors in development; on this front Morgan showed that sea urchin eggs could be induced to divide without fertilization by adding magnesium chloride.

Morgan's main lines of experimental work involved regeneration and larval development; in each case, his goal was to distinguish internal and external causes to shed light on the Roux-Driesch debate.

[citation needed] In 1904, his friend, Jofi Joseph died of tuberculosis, and he felt he ought to mourn her, though E. B. Wilson—still blazing the path for his younger friend—invited Morgan to join him at Columbia University.

Embryological development posed an additional problem in Morgan's view, as selection could not act on the early, incomplete stages of highly complex organs such as the eye.

The common solution of the Lamarckian mechanism of inheritance of acquired characters, which featured prominently in Darwin's theory, was increasingly rejected by biologists.

[16] In 1900 three scientists, Carl Correns, Erich von Tschermak and Hugo De Vries, had rediscovered the work of Gregor Mendel, and with it the foundation of genetics.

He was initially skeptical of Mendel's laws of heredity (as well as the related chromosomal theory of sex determination), which were being considered as a possible basis for natural selection.

Following C. W. Woodworth and William E. Castle, around 1908 Morgan started working on the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, and encouraging students to do so as well.

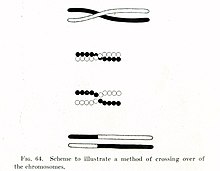

The observation of a miniature-wing mutant, which was also on the sex chromosome but sometimes sorted independently to the white-eye mutation, led Morgan to the idea of genetic linkage and to hypothesize the phenomenon of crossing over.

[22] In the following years, most biologists came to accept the Mendelian-chromosome theory, which was independently proposed by Walter Sutton and Theodor Boveri in 1902/1903, and elaborated and expanded by Morgan and his students.

Garland Allen characterized the post-1915 period as one of normal science, in which "The activities of 'geneticists' were aimed at further elucidation of the details and implications of the Mendelian-chromosome theory developed between 1910 and 1915."

[26] After 1915, he also became a strong critic of the growing eugenics movement, which adopted genetic approaches in support of racist views of "improving" humanity.

In 1927 after 25 years at Columbia, and nearing the age of retirement, he received an offer from George Ellery Hale to establish a school of biology in California.

In establishing the biology division, Morgan wanted to distinguish his program from those offered by Johns Hopkins and Columbia, with research focused on genetics and evolution; experimental embryology; physiology; biophysics, and biochemistry.

He wanted to attract the best people to the Division at Caltech, so he took Bridges, Sturtevant, Jack Shultz and Albert Tyler from Columbia and took on Theodosius Dobzhansky as an international research fellow.

In Evolution and Adaptation (1903), he argued the anti-Darwinist position that selection could never produce wholly new species by acting on slight individual differences.

Some of Morgan's students from Columbia and Caltech went on to win their own Nobel Prizes, including George Wells Beadle and Hermann Joseph Muller.