James Gregory (mathematician)

In his book Geometriae Pars Universalis (1668)[1] Gregory gave both the first published statement and proof of the fundamental theorem of the calculus (stated from a geometric point of view, and only for a special class of the curves considered by later versions of the theorem), for which he was acknowledged by Isaac Barrow.

His mother Janet was the daughter of Jean and David Anderson and his father was John Gregory,[9] an Episcopalian Church of Scotland minister, James was youngest of their three children and he was born in the manse at Drumoak, Aberdeenshire, and was initially educated at home by his mother, Janet Anderson (~1600–1668).

It was his mother who endowed Gregory with his appetite for geometry, her uncle – Alexander Anderson (1582–1619) – having been a pupil and editor of French mathematician Viète.

In 1663 he went to London, meeting John Collins and fellow Scot Robert Moray, one of the founders of the Royal Society.

At Padua he lived in the house of his countryman James Caddenhead, the professor of philosophy, and he was taught by Stefano Angeli.

Upon his return to London in 1668 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, before travelling to St Andrews in late 1668 to take up his post as the first Regius Professor of Mathematics at the University of St Andrews, a position created for him by Charles II, probably upon the request of Robert Moray.

About a year after assuming the Chair of Mathematics at Edinburgh, James Gregory suffered a stroke while viewing the moons of Jupiter with his students.

Before he left Padua, Gregory published Vera Circuli et Hyperbolae Quadratura (1667) in which he approximated the areas of the circle and hyperbola with convergent series: "The first proof of the fundamental theorem of calculus and the discovery of the Taylor series can both be attributed to him.

"[13][14] The book was reprinted in 1668 with an appendix, Geometriae Pars, in which Gregory explained how the volumes of solids of revolution could be determined.

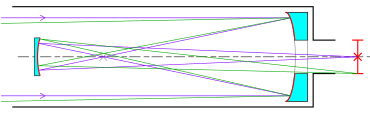

[15] The telescope design attracted the attention of several people in the scientific establishment such as Robert Hooke, the Oxford physicist who eventually built the telescope 10 years later, and Sir Robert Moray, polymath and founding member of the Royal Society.

...The most brilliant part of his character was that of his mathematical genius as an inventor, which was of the first order; as will appear by... his inventions and discoveries [which include] quadrature of the circle and hyperbola, by an infinite converging series; his method for the transformation of curves; a geometrical demonstration of Lord Brouncker's series for squaring the hyperbola—his demonstration that the meridian line is analogous to a scale of logarithmic tangents of the half complements of the latitude; he also invented and demonstrated geometrically, by help of the hyperbola, a very simple converging series for making the logarithms; he sent to Mr. Collins the solution of the famous Keplerian problem by an infinite series; he discovered a method of drawing Tangents to curves geometrically, without any previous calculations; a rule for the direct and inverse method of tangents, which stands upon the same principle (of exhaustions) with that of fluxions, and differs not much from it in the manner of application; a series for the length of the arc of a circle from the tangent, and vice versa; as also for the secant and logarithmic tangent and secant, and vice versa.

These, with others, for measuring the length of the elliptic and hyperbolic curves, were sent to Mr. Collins, in return for some received from him of Newton's, in which he followed the elegant example of this author, in delivering his series in simple terms, independent of each other.

[17] In a letter of 1671 to John Collins, Gregory gives the power series expansion of the seven functions (using modern notation)

[18] There is evidence that he discovered the method of taking higher derivatives in order to compute a power series, which was not discovered by Taylor until 1715, but did not publish his results, thinking he had only rediscovered "Mr. Newton's universal method," which was based on a different technique.

[20] In particular he observed the splitting of sunlight into its component colours – this occurred a year after Newton had done the same with a prism and the phenomenon was still highly controversial.