Gudermannian function

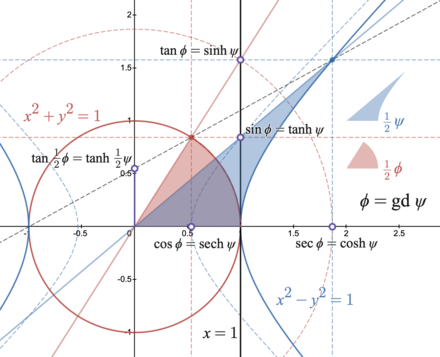

In mathematics, the Gudermannian function relates a hyperbolic angle measure

It was introduced in the 1760s by Johann Heinrich Lambert, and later named for Christoph Gudermann who also described the relationship between circular and hyperbolic functions in 1830.

The real Gudermannian function is typically defined for

to be the integral of the hyperbolic secant[3] The real inverse Gudermannian function can be defined for

as the integral of the (circular) secant The hyperbolic angle measure

are related by a common stereographic projection and this identity can serve as an alternative definition for

valid throughout the complex plane: We can evaluate the integral of the hyperbolic secant using the stereographic projection (hyperbolic half-tangent) as a change of variables:[5] Letting

we can derive a number of identities between hyperbolic functions of

and for complex arguments, care must be taken choosing branches of the inverse functions.

are all Möbius transformations of each-other (specifically, rotations of the Riemann sphere): For real values of

, these Möbius transformations can be written in terms of trigonometric functions in several ways, These give further expressions for

Analytically continued by reflections to the whole complex plane,

[9] For all points in the complex plane, these functions can be correctly written as: For the

the principal branch) or consider their domains and codomains as Riemann surfaces.

can be found by:[10] (In practical implementation, make sure to use the 2-argument arctangent,

can be found by:[11] Multiplying these together reveals the additional identity[8] The two functions can be thought of as rotations or reflections of each-other, with a similar relationship as

results in a half-turn rotation and translation in the codomain by one of

indicates the limit at one end of the infinite strip):[14] As the Gudermannian and inverse Gudermannian functions can be defined as the antiderivatives of the hyperbolic secant and circular secant functions, respectively, their derivatives are those secant functions: By combining hyperbolic and circular argument-addition identities, with the circular–hyperbolic identity, we have the Gudermannian argument-addition identities: Further argument-addition identities can be written in terms of other circular functions,[15] but they require greater care in choosing branches in inverse functions.

double-argument identities are The Taylor series near zero, valid for complex values

are the Euler secant numbers, 1, 0, -1, 0, 5, 0, -61, 0, 1385 ... (sequences A122045, A000364, and A028296 in the OEIS).

are same as the numerators of the Taylor series for sech and sec, respectively, but shifted by one place.

The function and its inverse are related to the Mercator projection.

The vertical coordinate in the Mercator projection is called isometric latitude, and is often denoted

Gerardus Mercator plotted his celebrated map in 1569, but the precise method of construction was not revealed.

In 1599, Edward Wright described a method for constructing a Mercator projection numerically from trigonometric tables, but did not produce a closed formula.

The closed formula was published in 1668 by James Gregory.

He called it the "transcendent angle", and it went by various names until 1862 when Arthur Cayley suggested it be given its current name as a tribute to Christoph Gudermann's work in the 1830s on the theory of special functions.

[19] Gudermann had published articles in Crelle's Journal that were later collected in a book[20] which expounded

Using Cayley's notation, He then derives "the definition of the transcendent", observing that "although exhibited in an imaginary form, [it] is a real function of

Points on one sheet of an n-dimensional hyperboloid of two sheets can be likewise mapped onto a n-dimensional hemisphere via stereographic projection.