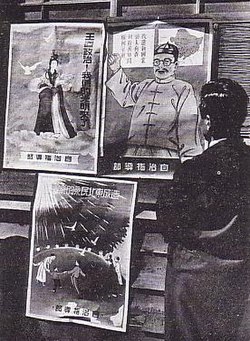

Propaganda in Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II

[5] By 1945 propaganda film production under the Japanese had expanded throughout the majority of their empire including Manchuria, Shanghai, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia.

[3] Most of the materials being shown were war news reels, Japanese motion pictures, or propaganda shorts paired with traditional Chinese films.

[6][7] China's rich history and exotic locations made it a favorite topic of Japanese film makers for over a decade before the outbreak of the second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).

[5] Among these films, Song of the White Orchid (1939, 白蘭の歌), China Nights (1940, 支那の夜), and Vow in the Desert (1940, 熱砂の誓い) mixed romantic melodrama with propaganda in order to represent a figurative and literal blending of the two cultures onscreen.

The risk of alienating the same cultures that the Japanese ostensibly were "liberating" from the yoke of Western colonial oppression was a powerful deterrent in addition to government pressure.

[5] Even so, as the war in China worsened for Japan, action films such as The Tiger of Malay (1943, マライの虎) and espionage dramas like The Man From Chungking (1943, 重慶から来た男) more overtly criminalized Chinese as enemies of the Empire.

Japan's first full-length animated feature film Momotarō: Divine Soldiers of the Sea (1945, 桃太郎海の神兵) similarly portrays the Americans and British in Singapore as morally decadent and physically weak "devils".

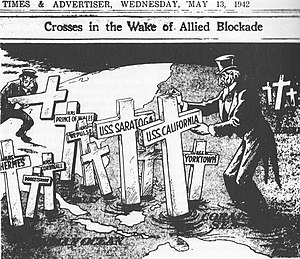

[13] Magazines were told that the cause of the war was the enemy's egoistic desire to rule the world, and ordered, under the guise of requests, to promote anti-American and anti-British sentiment.

[14] When Jun'ichirō Tanizaki began to serialize his novel Sasameyuki, a nostalgic account of pre-war family life, the editors of Chūōkōron were warned it did not contribute to the needed war spirit.

[30] Teachers were instructed to teach "Japanese science" based on the "Imperial Way", which precluded evolution in view of their claims to divine descent.

[34] Girls graduating on Okinawa heard a speech by their principal on how they must work hard to avoid shaming the school before they were inducted into the Student Corps to act as nurses.

[35] News reports were required to be official state announcements, read exactly, and as the war in China went on, even entertainment programs addressed wartime conditions.

[48] Kokutai, meaning the uniqueness of the Japanese people in having a leader with spiritual origins, was officially promulgated by the government, including a text book sent about by the Ministry of Education.

[56] Ancient texts set forth the central precepts of loyalty and filial piety, which would throw aside selfishness and allow them to complete their "holy task.

[61] Patriotic war songs seldom mentioned the enemy, and then only generically; the tone was elegiac, and the topic was purity and transcendence, often compared to cherry blossom.

[70] The attack on Iwo Jima was announced by the "Home and Empire" broadcast with uncommon praise of the American commanders but also the confident declaration that they must not leave the island alive.

[79] A campaign to promote fertility, in order to produce future citizens, continued through 1942, and no efforts were made to recruit women to war work for this reason.

[124] The dead were treated as "war gods", starting with the nine submariners who died at Pearl Harbor (with the tenth, taken prisoner, never being mentioned in Japanese press).

[134] Arguments that the plans for the Battle of Leyte Gulf, involving all Japanese ships, would expose Japan to serious danger if they failed, were countered with the plea that the Navy be permitted to "bloom as flowers of death.

[141] Vice Admiral Takijirō Ōnishi addressed the first kamikaze (suicide attack) unit, telling them that their nobility of spirit would keep the homeland from ruin even in defeat.

[143] These names were taken from a patriotic poem (waka or tanka), Shikishima no Yamato-gokoro wo hito towaba, asahi ni niou yamazakura bana by the Japanese classical scholar, Motoori Norinaga.

[146] Divers, prepared for such work in the event of the invasion of Japan, were given individual ensigns, to indicate they could replace an entire ship, and carefully separated so that they would die from their own handiwork rather than another's.

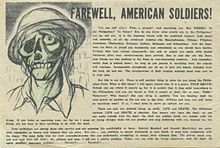

[158] The effect on Americans was tempered by subtle messages imbedded by the prisoners, including such comments as the declaration they were allowed to continue to wear the clothes they had been captured in.

[160] The United States and Great Britain were attacked years before the war, with any Western idea conflicting with Japanese practice being labeled "dangerous thoughts.

"[169] After such atrocities as the Bataan Death March, cruel treatment of prisoners of war was justified on the grounds they had sacrificed other people's lives but surrendered to save their own, and had acted with utmost selfishness throughout their campaign.

[172] The Meiji Restoration had plunged the nation into Western materialism (an argument that ignored commercialism and ribald culture in the Tokugawa era), which had caused people to forget they were a classless society under a benevolent emperor, but the war would shake off these notions.

Shinmin no Michi, the Path of the Subject, discussed American historical atrocities[56] and presented Western history as brutal wars, exploitation, and destructive values.

[56] Black propaganda posed as American instructions to avoid venereal disease by having sexual intercourse with wives or other respectable Filipina women rather than prostitutes.

[213] During the war with China, the prime minister announced on radio they were seeking only a new order to ensure the stability of East Asia, unfortunately prevented because Chiang Kai-shek was a Western puppet.

[221] The Japanese attempted to co-opt the Koreans, urging them to view themselves as part of one "imperial race" with Japan, and even presenting themselves as rescuing a nation too long under the shadow of China.