Jarvis Island

While a few offshore anchorage spots are marked on maps, Jarvis Island has no ports or harbors, and swift currents are a hazard.

[4] The center of Jarvis island is a dried lagoon where deep guano deposits accumulated, which were mined for about 20 years during the nineteenth century.

The low-lying coral island has long been noted as hard to sight from small ships and is surrounded by a narrow fringing reef.

Its sparse bunch grass, prostrate vines, and low-growing shrubs are primarily a nesting, roosting, and foraging habitat for seabirds, shorebirds, and marine wildlife.

[2] Jarvis Island was submerged underwater during the latest interglacial period, roughly 125,000 years ago, when sea levels were 5–10 meters (16–33 ft) higher than today.

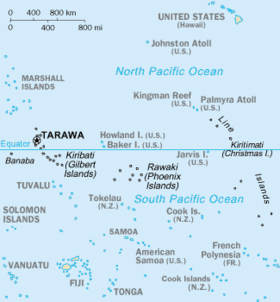

[8] Jarvis Island's highest point has a topographic isolation of 380.57 kilometers (236.48 mi; 205.49 nmi), with Joe's Hill on Kiritimati being the nearest higher neighbor.

The Polynesian storm petrel had made its return after over 40 years of absence from Jarvis Island, and the number of brown noddies multiplied from just a few birds in 1982 to nearly 10,000.

[11] The island, with its surrounding marine waters, has been recognized as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports colonies of lesser frigatebirds, brown and masked boobies, red-tailed tropicbirds, Polynesian storm petrels, blue noddies and sooty terns, as well as serving as a migratory stopover for bristle-thighed curlews.

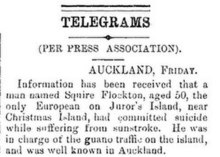

[18][19] Beginning in 1858, several support structures were built on Jarvis Island, along with a two-story, eight-room "superintendent's house" featuring an observation cupola and wide verandahs.

New Zealand entrepreneurs, including photographer Henry Winkelmann, then made unsuccessful attempts to continue guano extraction on Jarvis, and the two-story house was sporadically inhabited during the early 1880s.

Ocean Queen, and near the beach landing on the western shore, members of the crew built a pyramidal day beacon made from slats of wood, which was painted white.

On August 30, 1913, the barquentine Amaranth (C. W. Nielson, captain) was carrying a cargo of coal from Newcastle, New South Wales, to San Francisco when it wrecked on Jarvis' southern shore.

[22] Ruins of ten wooden guano-mining buildings, the two-story house among them, could still be seen by the Amaranth crew, who left Jarvis aboard two lifeboats.

The ship's scattered remains were noted and scavenged for many years, and rounded fragments of coal from the Amaranth's hold were still being found on the south beach in the late 1930s.

[2] Starting as a cluster of large, open tents pitched next to the still-standing white wooden day beacon, the Millersville settlement on the island's western shore was named after a bureaucrat with the United States Department of Air Commerce.

Believing that a U.S. Navy submarine had come to fetch them, the four young colonists rushed down the steep western beach in front of Millersville towards the shore.

[35] By the early 1960s, a few sheds, a century of accumulated trash, the scientists' house from the late 1950s, and a solid, short lighthouse-like day beacon built two decades before were the only signs of human habitation on Jarvis.

[41][43] Nineteenth-century tram track remains can be seen in the dried lagoon bed at the island's center, and the late 1930s-era lighthouse-shaped day beacon still stands on the western shore at the site of Millersville.

Public entry to anyone, including U.S. citizens, on Jarvis Island requires a special-use permit and is generally restricted to scientists and educators.