Palmyra Atoll

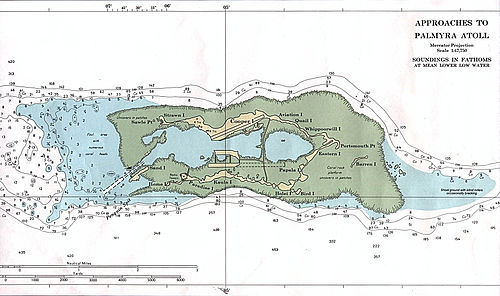

There is one boat anchorage, known as West Lagoon, accessible from the sea by a narrow artificial channel and an old airstrip; during WW2, it was turned into a Naval Air Station for several years and used for training and refueling.

[2] Palmyra Atoll has no permanent population, but in the sense of people living there, there is a steady stream of temporary staff and visitors for research, tourism, and other projects such as marine science or survey work.

The territory hosts a variable transient population of 4–25 staff and scientists employed by various departments of the U.S. government and by The Nature Conservancy,[3] as well as a rotating mix of Palmyra Atoll Research Consortium[4] scholars.

[6] The atoll consists of an extensive reef, three shallow lagoons, and a number of sand and reef-rock islets and bars covered with vegetation—mostly coconut palms, Scaevola, and tall Pisonia trees.

The atoll has nearly the highest oceanicity index (i.e., the degree to which its climate is affected by the sea) and one of the lowest diurnal and annual temperature variations of any place on Earth.

Naval Construction Battalion dredged a channel so that ships could enter the protected lagoons and bulldozed coral rubble into a long, unpaved landing strip for refueling transpacific supply planes at the airbase.

On January 16, 1942, six Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers from Hawaii were stationed at the airbase, commanded by Lt. Col. Walter C. Sweeney Jr. as part of Hawaiian Air Force's Task Group 8.

[30] On page 3, the Baltimore newspaper The Telegraphe and Daily Advertiser of July 29, 1803, appears to quote directly from Fanning's journal: "We supposed that we saw land from the masthead to the southward of the shoal (Kingman Reef) but it was so hazy we were not certain."

[35] A crew loaded it in secret onto the ship Esperanza in Callao harbor, Peru, and embarked into the Pacific Ocean on January 1, 1816, bound for the Spanish West Indies.

Before Hines died, he wrote letters describing the affair and the location of the treasure, which originally included 1.5 million Spanish gold pesos and an equal value in silver (possibly consisting of precolumbian artworks).

[43] On February 26, 1862, King Kamehameha IV of Hawaii commissioned Captain Zenas Bent and Johnson Beswick Wilkinson, both Hawaiian citizens, to take possession of the atoll.

After a legal challenge, Cooper's ownership of the atoll was held by the Supreme Court of Hawaii to be subject to rights sold by Ringer's widow to Henry Maui and Joseph Clarke.

[53] In September 1921, as part of a national push to better document the coastal and outlying areas owned by the United States, a small naval detachment was sent to Palmyra to conduct the first aerial surveys of the atoll.

The commanding officer and the aviators made a number of flights and the official photographer was in his element.At the time, Palmyra was occupied by three Americans: Colonel William Meng, his wife, and Edwin Benner Jr.[54] While there, the USS Eagle Boat 40, which had transported aircraft and photographic equipment to the islands, made a very rare exception to naval regulation and took aboard the wife, Mrs. Meng, to return her to Honolulu for medical aid, as she was not handling the isolation and trying physical conditions of Palmyra well.

Their three sons, including actor Leslie Vincent, continued as the owners afterward, subject to a period of military administration and construction by the Navy before and during World War II from 1939 through 1945.

"[58] Soon after this determination, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8616, officially, "Placing Palmyra Island, Territory of Hawaii, Under the Control and Jurisdiction of the Secretary of the Navy".

During negotiations, the government filed a quiet title action against the Fullard-Leos and Henry Ernest Cooper's six surviving children, claiming property at Palmyra had never been privately owned under the Kingdom of Hawaii or later.

The Insular Areas report states, "While the suit was pending during World War II, the Navy occupied Palmyra and built a runway and several buildings."

[44] In July 1938, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes wrote a letter to President Roosevelt, imploring him not to turn Palmyra over to the U.S. Navy for use as a military base.

The proclamation established the "Palmyra Island Naval Defensive Sea Area", encompassing the territorial waters between the extreme high-water marks and the three-mile marine boundaries surrounding the atoll.

[68] In the lobby of the "Transient Hotel" (built by the Seabees, and used by airmen on their way to the Pacific Theater front), a mural was hung depicting a quiet island scene.

After World War II, much of the Naval Air Station was demolished, with some of the materials piled up and burned on the atoll, dumped into the lagoon, or, in the case of unexploded ordnance on some islets, left in place.

The book led to a CBS television miniseries of the same name, starring James Brolin, Rachel Ward, Deidre Hall, and Hart Bochner; Richard Crenna played lawyer Bugliosi.

[77] In the late 1990s, Rachel Lahela Kekoa Bolt, a native Hawaiian heir of Henry Maui, and some of her descendants filed federal lawsuits claiming her inherited interest in Palmyra and challenging the legality of the Newlands Resolution that annexed Hawaii.

[82] One of the challenges has been understanding how the rich peaty soil that can be found on the island developed on the coral, and one of the overall goals is to maintain biodiversity globally in locations similar to Palmyra.

In January 2007, the commercial fishing licensees sued the United States in the Court of Federal Claims alleging that, under the Takings Clause, the Interior Department regulation had "directly confiscated, taken, and rendered wholly and completely worthless" their purported property interests.

In 2011, Fish and Wildlife Service, TNC, and Island Conservation began an extensive program to eradicate the horde of non-native rats that arrived on Palmyra during World War II.

As many as 30,000 rats once roamed the atoll, eating the eggs of native seabirds and destroying the seedlings of one of the largest remaining Pacific stands of Pisonia grandis trees.

The rats were eliminated in 2012; however, fifty-one animal samples representing 15 species of birds, fish, reptiles, and invertebrates were collected for residue analysis during systematic searches or as nontarget mortalities.

Other trees provide habitat for 11 seabird species, and the conservancy wrote that their re-establishment across the atoll would encourage coral growth and might lessen the local effects of a rise in sea-level.