Presidency of Charles de Gaulle

In the context of the Cold War, de Gaulle initiated his "politics of grandeur", asserting that France as a major power should not rely on other countries, such as the United States, for its national security and prosperity.

He restored cordial Franco-German relations to create a European counterweight between the Anglo-American and Soviet spheres of influence through the signing of the Élysée Treaty on 22 January 1963.

In his later years, his support for the slogan "Vive le Québec libre" and his two vetoes of Britain's entry into the European Economic Community generated considerable controversy in both North America and Europe.

Although reelected to the presidency in 1965, he faced widespread protests by students and workers in May 1968, but had the Army's support and won an election with an increased majority in the National Assembly.

De Gaulle's newly formed cabinet was approved by the National Assembly on 1 June 1958, by 329 votes against 224, while he was granted the power to govern by ordinances for a six-month period, as well as the task to draft a new Constitution.

France recognised Algerian independence on 3 July 1962, and a blanket amnesty law was belatedly voted in 1968, covering all crimes committed by the French army during the war.

[citation needed] With the conclusion of the Algerian War, de Gaulle was now able to seek his two main objectives: the reform and development of the French economy, and the promotion of an independent foreign policy and a strong presence on the international stage.

Several assassination attempts were made on him; the most famous occurred on 22 August 1962, when he and his wife narrowly escaped from an organized machine gun ambush on their Citroën DS limousine.

[16] After 1948, things began to improve dramatically with the introduction of Marshall Aid—large scale American financial assistance given to help rebuild European economies and infrastructure.

This laid the foundations of a meticulously planned program of investments in energy, transport and heavy industry, overseen by the government of Prime Minister Georges Pompidou.

With the cancellation of Blue Streak, the US agreed to supply Britain with its Skybolt and later Polaris weapons systems, and in 1958, the two nations signed the Mutual Defence Agreement forging close links which have seen the US and UK cooperate on nuclear security matters ever since.

Although at the time it was still a full member of NATO, France proceeded to develop its own independent nuclear technologies—this would enable it to become a partner in any reprisals and would give it a voice in matters of atomic control.

This surprising statement was intended as a declaration of French national independence and was in retaliation to a warning issued long ago by Dean Rusk that US missiles would be aimed at France if it attempted to employ atomic weapons outside an agreed plan.

Although the left progressed, the Gaullists won an increased majority—this despite opposition from the Christian democratic Popular Republican Movement (MRP) and the National Centre of Independents and Peasants (CNIP) who criticised de Gaulle's euroscepticism and presidentialism.

[25][26] De Gaulle's proposal to change the election procedure for the French presidency was approved at the referendum on 28 October 1962 by more than three-fifths of voters despite a broad "coalition of no" formed by most of the parties, opposed to a presidential regime.

As the last chief of government of the Fourth Republic, de Gaulle made sure that the Treaty of Rome creating the European Economic Community was fully implemented, and that the British project of Free Trade Area was rejected, to the extent that he was sometimes considered as a "Father of Europe".

[32] De Gaulle then tried to revive the talks by inviting all the delegates to another conference at the Élysée Palace to discuss the situation, but the summit ultimately dissolved in the wake of the U-2 incident.

De Gaulle, haunted by the memories of 1940, wanted France to remain the master of the decisions affecting it, unlike in the 1930s when it had to follow in step with its British ally.

Adenauer however, all too aware of the importance of American support in Europe, gently distanced himself from the general's more extreme ideas, wanting no suggestion that any new European community would in any sense challenge or set itself at odds with the US.

[36][page needed] De Gaulle vetoed the British application to join the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1963, famously uttering the single word 'non' into the television cameras at the critical moment, a statement used to sum up French opposition towards Britain for many years afterwards.

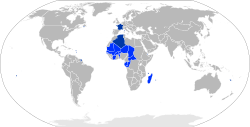

[40] In January 1964, France was, after the UK, among the first of the major Western powers to open diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China (PRC), which was established in 1949 and which was isolated on the international scene.

[41] By recognizing Mao Zedong's government, de Gaulle signaled to both Washington and Moscow that France intended to deploy an independent foreign policy.

[41] De Gaulle also used this opportunity to arouse rivalry between the USSR and China, a policy that was followed several years later by Henry Kissinger's "triangular diplomacy" which also aimed to create a Sino-Soviet split.

[41] With tension rising in the Middle East in 1967, de Gaulle on 2 June declared an arms embargo against Israel, just three days before the outbreak of the Six-Day War.

[45] In his letter to David Ben-Gurion dated 9 January 1968, de Gaulle explained that he was convinced that Israel had ignored his warnings and overstepped the bounds of moderation by taking possession of Jerusalem, and Jordanian, Egyptian, and Syrian territory by force of arms.

The Biafran chief of staff stated that the French "did more harm than good by raising false hopes and by providing the British with an excuse to reinforce Nigeria.

On 24 July, speaking to a large crowd from a balcony at Montreal's city hall, de Gaulle shouted "Vive le Québec libre!

His party won 352 of 487 seats,[64] but de Gaulle remained personally unpopular; a survey conducted immediately after the crisis showed that a majority of the country saw him as too old, too self-centered, too authoritarian, too conservative, and too anti-American.

[61] De Gaulle resigned the presidency at noon, 28 April 1969,[65] following the rejection of his proposed reform of the Senate and local governments in a nationwide referendum.

The draft closely followed the propositions in de Gaulle’s speech at Bayeux in 1946,[67] leading to a strong executive and to a rather presidential regime – the President being granted the responsibility of governing the Council of Ministers.