Jerusalem during the Second Temple period

There existed in the city, for example, a clear distinction between a rich and cosmopolitan elite and the wider population wishing less influence in the nation's ways from the outside world.

[15] The Exile allowed the worship of "Yahweh-alone" to emerge as the dominant theology of Yehud,[16] while the "sons of Yahweh" of the old pantheon evolved into angels and demons in a process that continued into the Hellenistic age.

This was a new idea, originating with the party of the golah, those who returned from the Babylonian exile;[17] behind the biblical narrative of Nehemiah and Ezra lies the fact that relations with the Samaritans and other neighbours were in fact close and cordial:[17] comparison between Ezra–Nehemiah and the Books of Chronicles bears this out: Chronicles opens participation in Yahweh-worship to all twelve tribes and even to foreigners, but for Ezra–Nehemiah "Israel" means Judah and Benjamin alone, plus the holy tribe of Levi.

[20] The urban area did not include the western hill (containing the Jewish, Armenian and Christian Quarters of modern Jerusalem), which had been inside the walls before the Babylonian destruction.

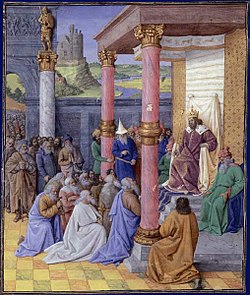

In 167 BCE, with tensions between Hellenized and observant Jews at their peak, Antiochus outlawed Jewish rites and traditions and desecrated the Temple, sparking off the Maccabean Revolt.

In the early 2nd century BCE, therefore, a rift existed in Jerusalem between an economically weak, observant majority lacking civic rights, and a small Hellenized minority closely linked to the Seleucid authorities and in control of the economy, trade, local administration and even the Temple itself.

Tensions were exacerbated by Antiochus' edicts against the Jewish faith, especially those introducing idol worship in the Temple and banning circumcision, and in 167 BCE a rural priest, Mattathias of Modi'in, led a rebellion against the Seleucid Empire.

The author, supposedly an Alexandrian Jew in the service of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (309–246 BCE), describes a visit to the city, including the Temple Mount and the adjacent citadel, the Ptolemaic Baris.

[30][31] The Hasmonean period in Jerusalem was characterized by great contrasts: independence and sovereignty, territorial expansion and material prosperity on the one hand, civil wars and a growing social gap on the other.

Under Salome some equilibrium was briefly restored between the monarchy and the Pharisees who controlled the Sanhedrin, but factional rifts reasserted themselves after her death, eventually leading to a state of constant civil war.

Lift up your eyes and look about you: All assemble and come to you; your sons come from afar, and your daughters are carried on the arm.Now the capital of an independent entity, Jerusalem of the Hasmonean period grew in size, population and wealth.

[37] With Jewish independence restored in the mid 2nd century BCE, the Hasmoneans quickly launched an effort to populate and fortify the Upper City, the western hill abandoned after the Babylonian sacking of Jerusalem.

Encompassing the City of David and the western hill, the walls were not entirely new but also incorporated elements of the earlier fortifications, such as the Iron Age "Israelite Tower" unearthed in the Jewish quarter.

It was probably during Alexander Jannæus' reign that the lower aqueduct was hewn, transporting water from the spring of Ein Eitam (near Bethlehem) to the vicinity of the Temple Mount.

The king carried great favor with his Roman patrons, towards which he was very generous, and therefore enjoyed considerable freedom of action to fortify both city and state without alarming Rome.

He built a large theatre, instituted wrestling tournaments in honor of the Emperor, staged spectacles where men fought wild animals,[27] and encouraged gentile immigration to Jerusalem.

[46] Philo, himself a Hellenized Jew, described Jerusalem during festivities: For innumerable companies of men from a countless variety of cities, some by land and some by sea, from east and from west, from the north and from the south, came to the Temple at every festivalThe pilgrims were economically crucial.

They came from all corners of the empire, bringing with them the latest news and innovations, conducting both retail and wholesale trade and providing a living for large segments of the local population.

Jerusalem did indeed make the desired impression and Roman historian Pliny the Elder described her as: by far the most famous city, not of Judæa only, but of the EastIn the religious sense, popular preoccupation with the Halakah laws of impurity and defilement is evident.

The outline of Herodian Jerusalem can be summarized thus: In the east, the city bordered the Kidron Valley, above which was built the huge retaining wall of the Temple Mount compound.

[53] To their south extended an area of ritual baths serving the pilgrims ascending the mount, and a street leading down to the City of David and the Pool of Siloam.

[62] Unlike the earlier structures which stood at the site, there are in fact many archaeological finds, including inscriptions, supporting Josephus' account of Herod's Temple.

[63] Herod expanded the Temple courtyard to the south, where he built the Royal Stoa, a basilica used for commercial purposes, similar to other forums of the ancient world.

Archaeologist Yosef Patrich has suggested that the Herodian theatre in Jerusalem was made of wood, as was customary at Rome at the time, which may explain the lack of finds.

Water was taken from Ein Eitam and Solomon's Pools, about 20 kilometers south of Jerusalem crow flies and about 30 meters higher in altitude than the Temple Mount.

Agrippa, however, never moved beyond the foundations, out of fear of emperor Claudius "lest he should suspect that so strong a wall was built in order to make some innovation in public affairs.

[66] It began in Jerusalem where it was led by local zealots who murdered and set fire to the house of the moderate high priest and a bonds archive in order to mobilize the masses.

Dominated by the moderate Pharisees, including Shimon ben Gamliel, president of the Sanhedrin, it appointed military commanders to oversee the defence of the city and its fortifications.

[70] Simon Bar Giora and John of Giscala, prominent Zealot leaders, placed all blame for the failure of the revolt on the shoulders of the moderate leadership.

[71] Josephus describes various acts of savagery committed against the people by its own leadership, including the torching of the city's food supply in an apparent bid to force the defenders to fight for their lives.