Jevons paradox

[1][2][3][4] Governments have typically expected efficiency gains to lower resource consumption, rather than anticipating possible increases due to the Jevons paradox.

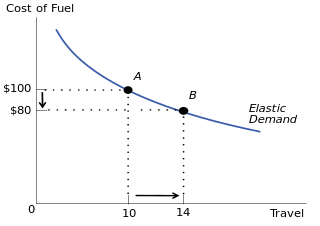

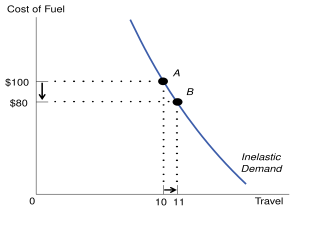

In addition to reducing the amount needed for a given use, improved efficiency also lowers the relative cost of using a resource, which increases the quantity demanded.

The Jevons paradox occurs when the effect from increased demand predominates, and the improved efficiency results in a faster rate of resource utilization.

[5] Some environmental economists have proposed that efficiency gains be coupled with conservation policies that keep the cost of use the same (or higher) to avoid the Jevons paradox.

Watt's innovations made coal a more cost-effective power source, leading to the increased use of the steam engine in a wide range of industries.

If in response, the amount of travel purchased more than doubles (i.e., demand is price elastic), then fuel consumption would increase, and the Jevons paradox would occur.

[14] The following conditions are necessary for a Jevons paradox to occur:[14] 1) Technological change which increases efficiency or productivity 2) The efficiency/productivity boost must result in a decreased consumer price for such goods or services 3) That reduced price must drastically increase quantity demanded (demand curve must be highly elastic) In the 1980s, economists Daniel Khazzoom and Leonard Brookes revisited the Jevons paradox for the case of society's energy use.

Khazzoom focused on the narrower point that the potential for rebound was ignored in mandatory performance standards for domestic appliances being set by the California Energy Commission.

[15][16] In 1992, the economist Harry Saunders dubbed the hypothesis that improvements in energy efficiency work to increase (rather than decrease) energy consumption the Khazzoom–Brookes postulate, and argued that the hypothesis is broadly supported by neoclassical growth theory (the mainstream economic theory of capital accumulation, technological progress and long-run economic growth).

Others, including many environmental economists, doubt this 'efficiency strategy' towards sustainability, and worry that efficiency gains may in fact lead to higher production and consumption.

First, in the context of a mature market such as for oil in developed countries, the direct rebound effect is usually small, and so increased fuel efficiency usually reduces resource use, other conditions remaining constant.

[8] The Jevons paradox indicates that increased efficiency by itself may not reduce fuel use, and that sustainable energy policy must rely on other types of government interventions as well.

[9] As the imposition of conservation standards or other government interventions that increase cost-of-use do not display the Jevons paradox, they can be used to control the rebound effect.

The ecological economists Mathis Wackernagel and William Rees have suggested that any cost savings from efficiency gains be "taxed away or otherwise removed from further economic circulation.

[30] Erik Brynjolfsson stated that he believes there will be some occupations for which the three conditions for the paradox will be met, thereby causing increased employment in those fields, such as radiologists, translators, and coders.