Peking opera

[4] Peking opera features four main role types, sheng (gentlemen), dan (women), jing (rough men), and chou (clowns).

[6] The repertoire of Peking opera includes over 1,400 works, which are based on Chinese history, folklore and, increasingly, contemporary life.

As it increased in popularity, its name became Jingju or Jingxi, which reflected its start in the capital city (Chinese: 京; pinyin: Jīng).

Beginning in 1884, the Empress Dowager Cixi became a regular patron of Peking opera, cementing its status over earlier forms like Kunqu.

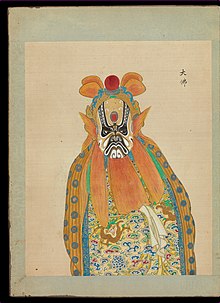

[16][17] At the time of its growth in the late nineteenth century, albums became used to display aspects of stage culture, including makeup and costumes of performers.

[22] The use of opera as a tool to transmit communist ideology reached its climax in the Cultural Revolution, under the purview of Jiang Qing, wife of Mao Zedong.

The "model operas" were considered one of the great achievements of the Cultural Revolution, and were meant to express Mao's view that "art must serve the interests of the workers, peasants, and soldiers and must conform to proletarian ideology.

[23] Notable among these operas was The Legend of the Red Lantern, which was approved as a concert with piano accompaniment based on a suggestion from Jiang Qing.

Regional, popular, and foreign techniques have been adopted, including Western-style makeup and beards and new face paint designs for Jing characters.

Performers have striven to introduce innovation in their work while heeding the call for reform from this new upper level of Peking-opera producers.

Although some, such as the actor Otis Skinner, believed that Peking opera could never be a success in the United States, the favorable reception of Mei and his troupe in New York City disproved this notion.

Wei Changsheng, a male Dan performer in the Qing court, developed the cai ciao, or "false foot" technique, to simulate the bound feet of women and the characteristic gait that resulted from the practice.

The clown is also connected to the small gong and cymbals, percussion instruments that symbolize the lower classes and the raucous atmosphere inspired by the role.

However, due to the standardization of Beijing opera and political pressure from government authorities, Chou improvisation has lessened in recent years.

Before the 20th century, students were often picked personally at a young age by a teacher and trained for seven years on account of the contract from the child's parents.

[59] Much attention is paid to tradition in the art form, and gestures, settings, music, and character types are determined by long-held convention.

This avoidance of sharp angles extends to three-dimensional movement as well; reversals of orientation often take the form of a smooth, S-shaped curve.

These plays usually center on one simple situation or feature a selection of scenes designed to include all four of the main Peking opera skills and showcase the virtuosity of the performers.

On formal occasions, lower officials may wear the kuan yi, a simple gown with patches of embroidery on both the front and back.

All other characters, and officials on informal occasions, wear the chezi, a basic gown with varying levels of embroidery and no jade girdle to denote rank.

Performers follow the basic principle that "strong centralized breath moves the melodic-passages" (zhong qi xing xiang).

"Stealing breath" is a sharp intake of air without prior exhalation, and is used during long passages of prose or song when a pause would be undesirable.

In addition to pronunciation differences that are due to the influence of regional forms, the readings of some characters have been changed to promote ease of performance or vocal variety.

Prose speeches were frequently improvised during the early period of Peking opera's development, and chou performers carry on that tradition today.

Song lyrics also use the speech tones of Mandarin Chinese in ways that are pleasing to the ear and convey proper meaning and emotion.

The Peking opera aesthetic for songs is summed up by the expression zi zheng qiang yuan, meaning that the written characters should be delivered accurately and precisely, and the melodic passages should be weaving, or "round".

Examples include the "Water Dragon Tune" (水龍吟; Shuǐlóng Yín), which generally denotes the arrival of an important person, and "Triple Thrust" (急三槍; Jí Sān Qiāng), which may signal a feast or banquet.

Of course, the aesthetic principle of synthesis frequently leads to the use of these contrasting elements in combination, yielding plays that defy such dichotomous classification.

[87] In 2017, Li Wenrui wrote in China Daily that 10 masterpieces of the traditional Peking opera repertoire are The Drunken Concubine, Monkey King, Farewell My Concubine, A River All Red, Wen Ouhong's Unicorn Trapping Purse ("the representative work of Peking Opera master Chen Yanqiu"), White Snake Legend, The Ruse of the Empty City (from Romance of the Three Kingdoms), Du Mingxin's Female Generals of the Yang Family, Wild Boar Forest, and The Phoenix Returns Home.

[89] In the 1993 film Farewell My Concubine, by Chen Kaige, Peking opera serves as the object of pursuit for the protagonists and a backdrop for their romance.