Johannes Gutenberg

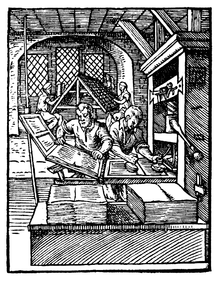

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg[a] (c. 1393–1406 – 3 February 1468) was a German inventor and craftsman who invented the movable-type printing press.

The printing press later spread across the world,[3] and led to an information revolution and the unprecedented mass-spread of literature throughout Europe.

[1][10] His exact year of birth is unknown; on the basis of a later document indicating that he came of age by 1420, scholarly estimates have ranged from 1393 to 1406.

[20] Because of his mother's commoner status, Gutenberg would never be able to succeed his father at the mint;[21] according to the historian Ferdinand Geldner [de] this disconnect may have disillusioned him from high society and encouraged his unusual career as an inventor.

[22][f] The patrician (Patrizier) class of Mainz—the Gutenbergs included—held a privileged socioeconomic status, and their efforts to preserve this put them into frequent conflict with the younger generations of guild (Zünfte) craftsmen.

[15][26] Friele left, presumably with the Gutenberg family, and probably stayed in the nearby Eltville since Else had inherited a house on the town walls there.

[28] The situation remained unstable and the rise of hunger riots forced the Gutenberg family to leave in January 1413 for Eltville.

[30] A knowledge of Latin—a prerequisite for universities—is also probable, though it is unknown whether he attended a Mainz parish school, was educated in Eltville or had a private tutor.

[31] Gutenberg may have initially pursued a religious career, as was common with the youngest sons of patricians, since the proximity of many churches and monasteries made it a safe prospect.

[32] He is assumed to have studied at the University of Erfurt, where there is a record of the enrollment of a student called Johannes de Altavilla in 1418—Altavilla is the Latin form of Eltville am Rhein.

[33] Nothing is now known of Gutenberg's life for the next fifteen years, but in March 1434, a letter by him indicates that he was living in Strasbourg, where he had some relatives on his mother's side.

The script is extremely neat and legible, not at all difficult to follow [You] would be able to read it without effort, and indeed without glasses" Around 1439, Gutenberg was involved in a financial misadventure making polished metal mirrors (which were believed to capture holy light from religious relics) for sale to pilgrims to Aachen: in 1439 the city was planning to exhibit its collection of relics from Emperor Charlemagne but the event was delayed by one year due to a severe flood and the capital already spent could not be repaid.

It was in Strasbourg in 1440 that he is said to have perfected and unveiled the secret of printing based on his research, mysteriously entitled Aventur und Kunst (enterprise and art).

In 1448, he was back in Mainz, where he took out a loan from his brother-in-law Arnold Gelthus, possibly for a printing press or related paraphernalia.

By this date, Gutenberg may have been familiar with intaglio printing; it is claimed that he had worked on copper engravings with an artist known as the Master of Playing Cards.

It is possible the large Catholicon dictionary, printed in Mainz in 1460 or later, was executed in his workshop, but there has been considerable scholarly debate.

[43] Meanwhile, the Fust–Schöffer shop was the first in Europe to bring out a book with the printer's name and date, the Mainz Psalter of August 1457, and while proclaiming the mechanical process by which it had been produced, it made no mention of Gutenberg.

In the following decades, punches and copper matrices became standardized in the rapidly disseminating printing presses across Europe.

In the standard process of making type, a hard metal punch (made by punchcutting, with the letter carved back to front) is hammered into a softer copper bar, creating a matrix.

After casting, the sorts are arranged into type cases, and used to make up pages which are inked and printed, a procedure which can be repeated hundreds, or thousands, of times.

Examination of transmitted light pictures of the page revealed substructures, in the type, that could not have been made using traditional punchcutting techniques.

Based on these observations, researchers hypothesized that Gutenberg's method involved impressing simple shapes in a "cuneiform" style onto a matrix made of a soft material, such as sand.

Thus, they speculated that "the decisive factor for the birth of typography", the use of reusable moulds for casting type, was a more progressive process than was previously thought.

However, the chronicle does not mention the name of Coster,[54][55] while it actually credits Gutenberg as the "first inventor of printing" in the very same passage (fol.

Every copy of printed books were identical; this was a significant departure from handwritten manuscripts, which left room for possible human error.

Everything can be traced to this source, but we are bound to bring him homage, … for the bad that his colossal invention has brought about is overshadowed a thousand times by the good with which mankind has been favored."

[64] As a result, Venzke describes the inauguration of the Renaissance, Reformation and humanist movement as "unthinkable" without Gutenberg's influence.

[71] The capital of printing in Europe shifted to Venice, where printers like Aldus Manutius ensured widespread availability of the major Greek and Latin texts.

Christopher Columbus had a geography book printed with movable type, bought by his father; it is now in the Biblioteca Colombina in Seville.

In 1952, the United States Postal Service issued a five hundredth anniversary stamp commemorating Johannes Gutenberg invention of the movable-type printing press.