John Bell (Tennessee politician)

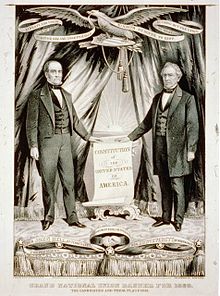

John Bell (February 18, 1796 – September 10, 1869) was an American politician, attorney, and planter who was a candidate for President of the United States in the election of 1860.

[2][3] He consistently battled Jackson's allies, namely James K. Polk, over issues such as the national bank and the election spoils system.

[1] Although a slaveholder,[4] Bell was one of the few Southern politicians to oppose the expansion of slavery to the territories in the 1850s, and he campaigned vigorously against secession in the years leading up to the American Civil War.

[1] During his 1860 presidential campaign, he argued that secession was unnecessary since the Constitution protected slavery, an argument that resonated with voters in border states, helping him capture the electoral votes of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia.

After the Battle of Fort Sumter in April 1861, marking the beginning of the Civil War, Bell abandoned the Union cause and supported the Confederacy.

[5]: 12 After serving a single term, Bell declined to run for reelection and instead moved to Nashville, where he established a law partnership with Henry Crabb.

[5]: 11 In 1826, Bell ran for Tennessee's 7th District seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, which had been vacated when the incumbent, Sam Houston, was elected governor.

Bell and his opponent, Felix Grundy, engaged in a bitter campaign in which both claimed to support the initiatives of Andrew Jackson.

[1] Although Jackson eventually endorsed Grundy, Bell was more popular with younger voters, and he won the election by just over a thousand votes.

One of the bill's most vocal opponents was Massachusetts congressman Edward Everett, Bell's future running mate in the 1860 presidential election.

[5]: 40 Following the shake-up of Jackson's cabinet in the wake of the Petticoat affair in 1831, Senator Hugh Lawson White recommended Bell for Secretary of War, but the appointment went to Lewis Cass instead.

[5]: 118 Jackson's friends were so elated at Bell's defeat that they held a gala at Vauxhall Gardens in Nashville, celebrating with champagne and the firing of cannons.

In March 1839, Bell's allies in the House engineered one last attack against Polk (who was retiring to run for governor) by removing the word "impartial" from his customary thanks for service.

[5]: 168–174 When the newly elected President Harrison organized his cabinet in 1841, he offered the position of Secretary of War to Bell, following the advice of Daniel Webster.

Finally, on September 11, 1841, two days after Tyler vetoed the Fiscal Corporation bill, Bell and several other cabinet members followed Clay's order and resigned in protest.

Bell, with the support of William "Parson" Brownlow's Jonesborough Whig and the Memphis Daily Eagle, was among those nominated to fill the seat.

After several weeks and 48 rounds of voting, Bell finally received the necessary majority on November 22, 1847, beating, among others, John Netherland, Robertson Topp, William B. Reese, and Christoper H.

[5]: 214 Shortly after his arrival in the Senate, Bell immediately began speaking out against the Mexican–American War, arguing it was a tyrannical endeavor of his old rival, James K. Polk, who was now president.

To gain the support of Southern senators, the bill contained an amendment that repealed part of the Missouri Compromise to allow slavery north of the 36°30' parallel.

Although Bell's term didn't expire for another two years, the legislature was so disgusted with him that they went ahead and chose his replacement (Alfred O. P. Nicholson) and demanded that he resign.

[5]: 336 Annoyed by the continuous sectional strife in the Senate, Bell throughout the 1850s had pondered forming a third party to attract moderates from both the North and South.

Houston's military endeavors had brought him national renown, but he reminded the convention's Clay Whigs of their old foe Andrew Jackson.

[5]: 368 However, Bell and his supporters knew they still needed to finish in the top three in the electoral college to be eligible for the contingent election as per the provisions of the Twelfth Amendment.

After the Battle of Fort Sumter in April, however, Bell, despite continuing to believe in the illegality of secession, complained that he felt deceived by Lincoln.

Accordingly, on April 23, he openly opposed Lincoln, called for the state to align itself with the Confederacy, and urged that it prepare a defense against a federal invasion.

Louisville Journal editor George D. Prentice wrote that Bell's decision brought "unspeakable mortification, and disgust, and indignation" to his long-time supporters.

[5]: 401 Knoxville Whig editor (and future Tennessee governor) William Brownlow derided Bell as the "officiating Priest" at the altar of the "false god of Disunion.

In June 1861, Bell traveled to Knoxville in hopes of converting the city's Unionist leaders to the secessionist cause and perhaps changing sentiments in the state's east, where most people remained pro-Union.

"[11] Temple surmised that Bell's decision to support the Confederacy was driven by panic, for "there was not a drop of disloyal blood in his veins.

[5]: 12 Bell's great-grandson, also named Edwin A. Keeble, was a prominent Nashville-area architect, his best known design being the city's first skyscraper, the Life & Casualty Tower.