John Brown's last speech

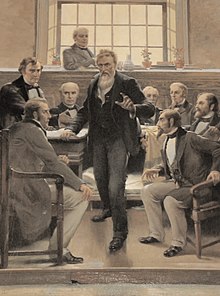

[3][4][5] As was his custom, Brown spoke extemporaneously and without notes, although he had evidently thought about what he would say and he knew the opportunity was coming.

The American Anti-Slavery Society then predicted that his execution would begin his martyrdom, or that potential clemency would remove "so much capital [...] out of the abolition sails".

Virginia court procedure required that defendants found guilty should be asked if there was any reason the sentence should not be imposed.

Asked this by the clerk, Brown immediately rose, and in a clear, distinct voice said this:[6] I have, may it please the court, a few words to say.

I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter, when I went into Missouri and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada.

I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.

Had I interfered in the manner which I admit, and which I admit has been fairly proved (for I admire the truthfulness and candor of the greater portion of the witnesses who have testified in this case), had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends, either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class, and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.

I never had any design against the life of any person, nor any disposition to commit treason, or excite slaves to rebel, or make any general insurrection.

"One indecent fellow, behind the Judge's chair, shouted and clapped hands jubilantly; but he was indignantly checked, and in a manner that induced him to believe that he would do best to retire.

A verse on the title page, "He, being dead, yet speaketh" (Hebrews 11:4), compares Brown with Abel, killed by Cain.

[13] Though the talk had been scheduled in advance, on "The Lesson of the Hour", the topic of John Brown had not been announced and was a surprise to those present.

There is no civil society, no government; nor can such exist except on the basis of impartial equal submission of its citizens—by a performance of the duty of rendering justice between God and man.

The yet undefined action of observation would be "the first step towards making Brown a Martyr, but should Governor Wise see fit to reprieve him, so much capital will be taken out of the abolition sails".

[17] The prosecuting attorney, Andrew Hunter, published 30 years later his recollections of the speech: When called upon and asked whether he had anything to say why sentence should not be executed according to the verdict of the jury, he rose and made a formal and evidently well considered speech, in which, to my great surprise, he declared that his purpose in coming here was not to arm the slaves against their masters and incite an insurrection, but it was simply to do on a larger scale what he had done in Kansas; to run them off, so as to secure their freedom, into the free states.

Wise came on to Charlestown not long after it made its appearance, and mentioned to me his great surprise to have read such a speech coming from Capt.

Why had he collected the Sharpe's rifles, the pikes, the kegs of powder, many thousands of caps and much war-like material at the Kennedy farm?

[20] Brown's biographer David S. Reynolds claims, "The Gettysburg Address similarly glossed over disturbing details in the interest of making a higher point.