John Gabriel Stedman

John Gabriel Stedman (1744 – 7 March 1797) was a Dutch States Army officer and writer best known for writing The Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796).

This narrative covers describes his experience in Suriname between 1773 and 1777, where he was a soldier in a Dutch regiment deployed to assist colonial troops fighting against groups of Maroons.

The Narrative was a bestseller of the time and, with its firsthand depictions of slavery and other aspects of colonialism, became an important tool in the fledgling abolitionist movement.

[3] His corps comprised 800 volunteers to be sent to Surinam aboard the frigate Zeelust to assist local troops fighting against marauding bands of escaped slaves, known as Maroons, in the eastern region of the colony.

Stedman believed that Fourgeoud neglected his duties as an officer, ignoring the well-being of his troops, and that he only retained his title through monetary bribes.

[5] On 10 August 1775, shortly after falling ill in Surinam, Stedman wrote Colonel Fourgeoud a letter requesting both a furlough to regain health and six months' military pay that was owed him.

[6] In addition to the 800 European soldiers, Stedman fought alongside the newly formed Free Negro Corps, which consisted of Black slaves purchased from their enslavers.

While Stedman kept a diary of his time in Surinam, which is held by the University of Minnesota Libraries, the Narrative manuscript wasn't composed until ten years after his return to Europe.

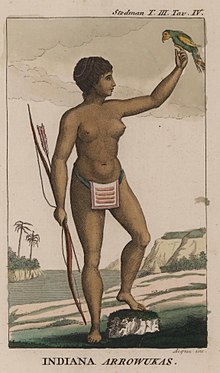

His observations of life in the colony encompass the different cultures present at the time: Dutch, Scottish, native, African, Spanish, Portuguese, and French.

Stedman writes that parts of Surinam are mountainous, dry, and barren, but much of the land is ripe and fertile, enjoying a year-long growing season, with rains and a warm climate.

In one story detailed in his Narrative, involving a group sailing by boat, an enslaved mother was ordered by her mistress to hand over her crying baby.

He was condemned for the support and publication of writers who voiced liberal opinions, such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine.

It was translated into French, German, Dutch, Italian, and Swedish, and was eventually published in more than twenty-five different editions, including several abolitionist tracts focused on Joanna.

Examination of the original notebooks and papers that Thompson had used (which are now in the James Ford Bell Library at the University of Minnesota) revealed that, not only had he inserted his own commentary into that of Stedman...but he had changed dates and spellings, misread and incorrectly transcribed a large number of words".

[21] Torn between the roles of "incurable romantic"[9] and scientific observer, Stedman attempted to maintain an objective distance from this strange new world, but was drawn in by its natural beauty and what he perceived as its exoticness.

[9] Stedman made a daily effort to take notes on the spot, using any material in sight that could be written on, including ammunition cartridges and bleached bone.

Stedman later transcribed the notes and strung them together in a small green notebook and ten sheets of paper covered front and back with writing.

[2] He elaborated on his opposition to authority figures, which he also described during his time in Surinam, and on the sympathy he felt towards creatures and humans unnecessarily punished or tortured.

[30] In fact, Stedman believed that slavery was necessary in some form to continue allowing European nations to indulge their excessive desires for commodities such as tobacco and sugar.

His sympathy for the suffering slaves, expressed throughout the book, is consistently obfuscated by his opinion about slavery as an institution, which according to Werner Sollors was "complicated, its representation strongly affected by the revisions.

[34] Stedman details frequent sexual encounters with free and enslaved women of African descent in his travel diary, beginning on 9 February 1773, the night he arrived in Suriname's capital, Paramaribo.

[28] 9 February is recounted with the following entry: "Our troops were disembarked at Parramaribo...I get fudled [sic] at a tavern, go to sleep at Mr. Lolkens, who was in the country, I f—k one of his negro maids".

The image-conscious Stedman, with a wife and children back in Europe, wanted to cultivate the impression of a gentleman rather than the serial adulterer he portrays in his diaries.

He often describes instances of what he viewed as her loyalty and devotion to him through his absences and illnesses: "She told me she had heard of my forlorn situation; and if I still entertained for her the same good opinion I had formerly expressed, her only request was that she might be permitted to wait upon me till I recovered.

"[38]In the nineteenth century, abolitionists circulated Stedman and Joanna's story, most notably in Lydia Maria Child's collection The Oasis in 1834.

Together they settled in Tiverton, Devonshire, and had five children: Sophia Charlotte, Maria Joanna, George William, Adrian, and John Cambridge.

John Cambridge served as captain of the 34th Light Infantry of the East India Company military and was killed in an attack on Rangoon in 1824.

According to the Dictionary of National Biography, family tradition maintains that Stedman suffered a severe accident around 1796 which prevented him from commanding a regiment at Gibraltar.

Instructions left by Stedman before his death requested that he be buried in the parish of Bickleigh next to self-styled gypsy king Bampfylde Moore Carew.

Stedman's final request was apparently not honored in full, as his grave lies in front of the vestry door, on the opposite side of the church from Carew.