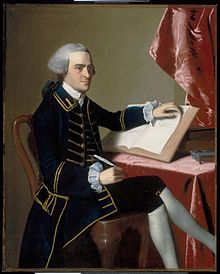

John Hancock

And much to the frustration of the British authorities, when seizures did happen local merchants were often able to use sympathetic provincial courts to reclaim confiscated goods and have their cases dismissed.

[26] Soon after, Parliament passed the Stamp Act 1765, a tax on legal documents such as wills that had been levied in Britain for many years but which was wildly unpopular in the colonies, producing riots and organized resistance.

Hancock initially took a moderate position: as a loyal British subject, he thought that the colonists should submit to the act even though he believed that Parliament was misguided.

[29] Hancock's political success benefited from the support of Samuel Adams, the clerk of the House of Representatives and a leader of Boston's "popular party", also known as "Whigs" and later as "Patriots".

[33] Historian William M. Fowler, who wrote biographies of both men, argues that this characterization was an exaggeration and that the relationship between the two was symbiotic, with Adams as the mentor and Hancock the protégé.

They may have suspected that he was a smuggler or they may have wanted to harass him because of his politics, especially after Hancock snubbed Governor Francis Bernard by refusing to attend public functions when the customs officials were present.

[41][42][43][44] Customs officials wanted to file charges, but the case was dropped when Massachusetts Attorney General Jonathan Sewall ruled that Hancock had broken no laws.

[52][48] One month later, while the British warship HMS Romney was in port, one of the tidesmen changed his story: he claimed that he had been forcibly held on the Liberty while it had been illegally unloaded.

With John Adams serving as his lawyer, Hancock was prosecuted in a highly publicized trial by a vice admiralty court, which had no jury and was not required to allow the defense to cross-examine the witnesses.

"[73] Historian Oliver Dickerson argues that Hancock was the victim of an essentially criminal racketeering scheme perpetrated by Governor Bernard and the customs officials.

[79] Biographer William Fowler concludes that while Hancock was probably engaged in some smuggling, most of his business was legitimate, and his later reputation as the "king of the colonial smugglers" is a myth without foundation.

Lord Hillsborough, secretary of state for the colonies, sent four regiments of the British Army to Boston to support embattled royal officials and instructed Governor Bernard to order the Massachusetts legislature to revoke the Circular Letter.

Meeting with Bernard's successor, Governor Thomas Hutchinson, and the British officer in command, Colonel William Dalrymple, Hancock claimed that there were 10,000 armed colonists ready to march into Boston if the troops did not leave.

[84][85] Hutchinson knew that Hancock was bluffing, but the soldiers were in a precarious position when garrisoned within the town, and so Dalrymple agreed to remove both regiments to Castle William.

[92][93] In April 1772, Hutchinson approved Hancock's election as colonel of the Boston Cadets, a militia unit whose primary function was to provide a ceremonial escort for the governor and the General Court.

They cooperated in the revelation of private letters of Thomas Hutchinson, in which the governor seemed to recommend "an abridgement of what are called "English liberties" to bring order to the colony.

Hancock's speech denounced the presence of British troops in Boston, who he said had been sent there "to enforce obedience to acts of Parliament, which neither God nor man ever empowered them to make".

On June 17, the Massachusetts House elected five delegates to send to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, which was being organized to coordinate colonial response to the Coercive Acts.

[113][116] Gage received a letter from Lord Dartmouth on April 14, 1775, advising him "to arrest the principal actors and abettors in the Provincial Congress whose proceedings appear in every light to be acts of treason and rebellion".

From Boston, Joseph Warren dispatched messenger Paul Revere to warn Hancock and Adams that British troops were on the move and might attempt to arrest them.

Soon after the battle, Gage issued a proclamation granting a general pardon to all who would "lay down their arms, and return to the duties of peaceable subjects"—with the exceptions of Hancock and Samuel Adams.

[145] In 1777, a Harvard committee headed by James Bowdoin, Hancock's chief political and social rival in Boston, sent a messenger to Philadelphia to retrieve the money and records.

[147][148][149] When Harvard replaced Hancock as treasurer, his ego was bruised and for years he declined to settle the account or pay the interest on the money he had held, despite pressure put on him by Bowdoin and other political opponents.

[154] He chaired the Marine Committee and took pride in helping to create a small fleet of American frigates, including the USS Hancock, which was named in his honor.

[163] Known as the engrossed copy, this is the famous document on display at the National Archives in Washington, D.C.[164] In October 1777, after more than two years in Congress, Hancock requested a leave of absence.

Bowdoin, his principal opponent, was cast by Hancock's supporters as unpatriotic, citing among other things his refusal (which was due to poor health) to serve in the First Continental Congress.

[181] Hancock governed Massachusetts through the end of the Revolutionary War and into an economically troubled postwar period, repeatedly winning re-election by wide margins.

As was the custom in an era where political ambition was viewed with suspicion, Hancock did not campaign or even publicly express interest in the office; he instead made his wishes known indirectly.

[201][202] By order of acting governor Samuel Adams, the day of Hancock's burial was a state holiday; the lavish funeral was perhaps the grandest given to an American up to that time.

According to historian Charles Akers, "The chief victim of Massachusetts historiography has been John Hancock, the most gifted and popular politician in the Bay State's long history.