John Harvard (clergyman)

[3] Harvard was born in Southwark, England, and earned bachelor's and master's degrees from Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

In 1637 he emigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, in British America, where he became a teaching elder and assistant preacher of the First Church in Charlestown.

[8][9] In the spring or summer of 1637, the couple emigrated to the New England Colonies, where Harvard became a freeman of Massachusetts[6] and, settling in Charlestown, a teaching elder of the First Church there[10] and an assistant preacher, though it is not known whether he was episcopally ordained.

[11][11] In 1638, a tract of land was deeded[clarification needed] to him there, and he was appointed that same year to a committee "to consider of some things tending toward a body of laws.

In 1828, Harvard University alumni erected a granite monument to his memory there,[6][13] his original stone having disappeared during the American Revolution.

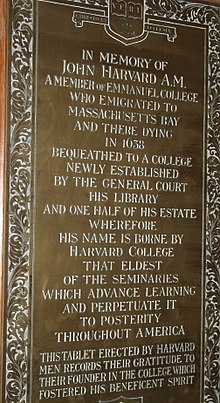

[14] Two years before Harvard's death the Great and General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony—desiring to "advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity: dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches, when our present ministers shall lie in the dust"—appropriated £400 toward a "schoale or colledge"[3] at what was then called Newtowne.

[15] In an oral will spoken to his wife[16] the childless Harvard, who had inherited considerable sums from his father, mother, and brother,[17] bequeathed to the school £780—half of his monetary estate—with the remainder to his wife;[4] this bequest was roughly equal to the Massachusetts Bay Colony's annual tax receipts.

But if the founding is to be regarded as a process rather than as a single event [then John Harvard, by virtue of his bequest "at the very threshold of the College's existence and going further than any other contribution made up to that time to ensure its permanence"] is clearly entitled to be considered a founder.