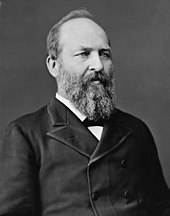

John Hay

Hay recalled an early encounter with Lincoln: He came into the law office where I was reading ... with a copy of Harper's Magazine in hand, containing Senator Douglas's famous article on Popular Sovereignty.

"[22] Hay continued to write, anonymously, for newspapers, sending in columns calculated to make Lincoln appear a sorrowful man, religious and competent, giving of his life and health to preserve the Union.

[24] Despite the heavy workload—Hay wrote that he was busy 20 hours a day—he tried to make as normal a life as possible, eating his meals with Nicolay at Willard's Hotel, going to the theater with Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln, and reading Les Misérables in French.

Lincoln doubted that they actually spoke for Confederate President Jefferson Davis, but had Hay journey to New York to persuade the publisher to go to Niagara Falls, Ontario, to meet with them and bring them to Washington.

[36] The two men were also motivated to find new jobs by their deteriorating relationship with Mary Lincoln, who sought their ouster, and by Nicolay's desire to wed his intended—he could not bring a bride to his shared room at the White House.

[46] Initially happy to be home, Hay quickly grew restive,[47] and he was glad to hear, in early June 1867, that he had been appointed secretary of legation to act as chargé d'affaires at Vienna.

[48] The Vienna post was only temporary, until Johnson could appoint a chargé d'affaires and have him confirmed by the Senate, and the workload was light, allowing Hay, who was fluent in German, to spend much of his time traveling.

[59] His work at the Tribune came as his fame as a poet was reaching its peak, and one colleague described it as "a liberal education in the delights of intellectual life to sit in intimate companionship with John Hay and watch the play of that well-stored and brilliant mind".

[60] In addition to writing, Hay was signed by the prestigious Boston Lyceum Bureau, whose clients included Mark Twain and Susan B. Anthony, to give lectures on the prospects for democracy in Europe, and on his years in the Lincoln White House.

This changed when the 1896 Democratic National Convention nominated former Nebraska congressman William Jennings Bryan on a "free silver" platform; he had electrified the delegates with his Cross of Gold speech.

"[97][98] Once Hay returned to the United States in early August, he went to The Fells and watched from afar as Bryan barnstormed the nation in his campaign while McKinley gave speeches from his front porch.

[99] In October, after basing himself at his Cleveland home and giving a speech for McKinley, Hay went to Canton at last, writing to Adams, I had been dreading it for a month, thinking it would be like talking in a boiler factory.

[100]Hay was disgusted by Bryan's speeches, writing in language that Taliaferro compares to The Bread-Winners that the Democrat "simply reiterates the unquestioned truths that every man with a clean shirt is a thief and ought to be hanged: that there is no goodness and wisdom except among the illiterate & criminal classes".

[103] According to Taliaferro, "only after the deed was accomplished and Hay was installed as the ambassador to the Court of St. James's would it be possible to detect just how subtly and completely he had finessed his ally and friend, Whitelaw Reid".

[109] In his Thanksgiving Day address to the American Society in London in 1897, Hay echoed these points, "The great body of people in the United States and England are friends ... [sharing] that intense respect and reverence for order, liberty, and law which is so profound a sentiment in both countries".

The British would only join if the Indian colonial government (on a silver standard until 1893) was willing; this did not occur, and coupled with an improving economic situation that decreased support for bimetallism in the United States, no agreement was reached.

British response to Hay's promotion was generally positive, and Queen Victoria, after he took formal leave of her at Osborne House, invited him again the following day, and subsequently pronounced him, "the most interesting of all the Ambassadors I have known.

When the foreign relief force, principally Japanese but including 2,000 Americans, relieved the legations and sacked Peking, China was made to pay a huge indemnity but there was no cession of land.

[146] The summer of 1901 was tragic for Hay; his older son Adelbert, who had been consul in Pretoria during the Boer War and was about to become McKinley's personal secretary, died in a fall from a hotel window.

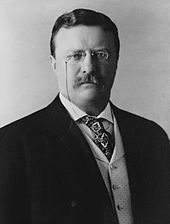

With Vice President Roosevelt and much of the cabinet hastening to the bedside of McKinley, who had been operated on (it was thought successfully) soon after the shooting, Hay planned to go to Washington to manage the communication with foreign governments, but presidential secretary George Cortelyou urged him to come to Buffalo.

Shortly before Hay took office, Britain and the U.S. agreed to establish a Joint High Commission to adjudicate unsettled matters, which met in late 1898 but made slow progress, especially on the Canada-Alaska boundary.

The first Hay–Pauncefote Treaty was sent to the Senate the following month, where it met a cold reception, as the terms forbade the United States from blockading or fortifying the canal, that was to be open to all nations in wartime as in peace.

By prearrangement, Bunau-Varilla was appointed representative of the nascent nation in Washington, and quickly negotiated the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty, signed on November 18, giving the United States the right to build the canal in a zone 10 miles (16 km) wide, over which the U.S. would exercise full jurisdiction.

[179] One incident involving Hay that benefitted Roosevelt politically was the kidnapping of Greek-American playboy Ion Perdicaris in Morocco[d] by chieftain Mulai Ahmed er Raisuli, an opponent of Sultan Abdelaziz.

Early 1905 saw futility for Hay, as a number of treaties he had negotiated were defeated or amended by the Senate—one involving the British dominion of Newfoundland due to Senator Lodge's fears it would harm his fisherman constituents.

[194] In 1865, early in his Paris stay, Hay penned "Sunrise in the Place de la Concorde", a poem attacking Napoleon III for his reinstitution of the monarchy, depicting the Emperor as having been entrusted with the child Democracy by Liberty, and strangling it with his own hands.

His 1871 poem, "The Prayer of the Romans", recites Italian history up to that time, with the Risorgimento in progress: liberty cannot be truly present until "crosier and crown pass away", when there will be "One freedom, one faith without fetters,/One republic in Italy free!

"[199] Castilian Days, souvenir of Hay's time in Madrid, is a collection of seventeen essays about Spanish history and customs, first published in 1871, although several of the individual chapters appeared in The Atlantic in 1870.

[217] Sale of the serialization rights to The Century magazine, edited by Hay's friend Richard Gilder, helped give the pair the impetus to bring what had become a massive project to an end.

[239] According to historian Lewis L. Gould, in his account of McKinley's presidency, One of the most entertaining and interesting letter writers who ever ran the State Department, the witty, dapper, and bearded Hay left behind an abundance of documentary evidence on his public career.