John Mirk

He is noted as the author of widely copied, and later printed, books intended to aid parish priests and other clergy in their work.

His use of language and his name suggest he may have originated in northern England, a region strongly influenced by Norse settlement and culture.

[3] This has similarities to the work of lay catechesis pioneered under John of Thoresby, the Archbishop of York a generation earlier.

The defining event in Mirk's background was the Black Death,[4] which killed half the population and had major and protracted consequences for society and economy, as well as the spiritual life of the survivors.

However, Shropshire's agrarian crisis started much earlier in the century, with a major cattle murrain and crop failures between 1315 and 1322[5] Moreover, the prolonged recovery from the disasters was jeopardised by the disorder of the early years of Henry IV's reign, when Owain Glyndŵr's revolt and the uprisings of discontented English nobles devastated many areas.

[6] Richard de Belmeis, one of the founders, was dean of the collegiate church of St Alkmund in Shrewsbury and was able to have the college suppressed and its wealth turned over to the abbey.

Lilleshall was brought to a nadir in the early 14th century by the agrarian crisis and the mismanagement and criminality of some abbots, notably John of Chetwynd,[6] but made a surprisingly good recovery, largely through a reorganisation imposed by William de Shareshull.

By Mirk's time, the abbey had entered a period of stability, reflected in a relatively high standard of monastic life and liturgy.

Shortly afterwards, King Richard and his uncle, John of Gaunt, both stayed at Lilleshall Abbey, in connection with a session of Parliament[6] held from 27 to 31 January in Shrewsbury, which brought looting by members of the royal household.

[10] It is not surprising that the Archbishop and Thomas FitzAlan, 12th Earl of Arundel, his nephew, were closely involved from the outset in the new Lancastrian regime of Henry IV, who seized power in 1399.

The Battle of Shrewsbury, decisively securing Henry's grip on power, was fought just to the north of the town in 1403, causing considerable damage to the surrounding area.

In 1407, for example, a group of Arundel's retainers, including Robert Corbet, his brother Roger together donated a house in Shrewsbury to the Abbey.

[13] This all clashed with popular religion as practised locally, with its lucrative cult of St Winifred and its highly organised celebration of Corpus Christi, featuring procession of the town's many trades.

[14] Thorpe was arrested, together with his associate, John Pollyrbach, and interviewed by Thomas Prestbury, the abbot of Shrewsbury, before being despatched to Archbishop Arundel.

[13] Thorpe's Testimony, purporting to recount these interviews, portrays the ensuing interchange as a victory for himself against Arundel, who was an enthusiastic persecutor of Lollards.

[15] Whatever the truth of this, Arundel sent commissions to Shropshire in May 1407 to arrest suspected Lollards,[16] suggesting that the movement was perceived as a threat locally.

He began with Advent Sunday and worked his way through to All Saints' Day, with a final sermon for the consecration of a church, although the order is disturbed to some extent in some manuscripts.

His most important source was the Golden Legend,[1] an immensely popular collection of hagiographies compiled by Jacobus de Voragine in the mid-13th century.

His response was to present a compressed but comprehensive view of Christian teaching that privileges oral tradition above Biblical texts.

"[19] The homily for Corpus Christi defends the doctrine of Transubstantiation, which the festival celebrates and the Lollards rejected, with just such a story, concerning Oda of Canterbury.

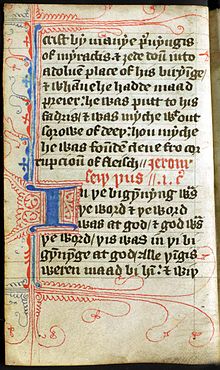

Over forty known manuscripts of the Festial are extant[1] but about half diverge greatly from Mirk's original, with much of the local colour removed.

Interest began to revive after the 1905, when the first volume of Theodore Erbe's edition, based primarily on a Gough manuscript in the Bodleian Library,[28] was published for the Early English Text Society.

[35] Archbishop John Peckham turned this into a clear list for his Archdiocese of Canterbury in the Lambeth Constitutions of 1281,[36] which promulgated a manual known as the Ignorantia sacerdotum.

John of Thoresby went further, largely reiterating Peckham's pronouncements[37] but also having them adapted and expanded into a vernacular verse document, known as the Lay Folks' Catechism[38] for his Archdiocese of York, in 1357.

Both these catechetical manuals set out six key areas to cover: The Creed (condensed to a 14-point summary), the Ten Commandments, The Seven Sacraments, the Seven Deeds of Mercy, the Seven Virtues, the Seven Deadly Sins.

[55] After a series of instructions for those that are "mene of lore," the least learned priests,[56] Mirk's conclusion asks that the reader pray for the author.

[1] An edition, prepared for the Early English Text Society by Edward Peacock, was published in 1868 and revised in 1902 by Frederick James Furnivall.

[1] It has not yet been printed, although a critical edition by Susan Powell and James Girsch, based on Bodleian Library MS Bodley 632, is planned.