The Yankee

Many new, predominantly female, writers and editors started their careers with contributions and criticism of their work published in The Yankee, including many who are familiar to modern readers.

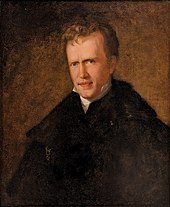

[1] After gaining national recognition as a critic, poet, and novelist,[2] he sailed to London, where he wrote for British magazines and served as Jeremy Bentham's secretary.

[5] Neal experienced verbal taunting and physical violence in the streets[6] and an attempt to block his admission to the local bar association, though he had been a practicing lawyer in Baltimore (1820–1823).

[20] Because Neal included a high proportion of his own work, self-promotion, and details of feuds with other public figures, "no magazine ever bore more fully the stamp of a personality",[20] according to scholar Irving T. Richards.

[30] Whittier sought Neal's opinion in the magazine at a turning point in the poet's career, saying when he submitted a poem that "if you don't like it, say so privately; and 'I will quit poetry, and everything also of a literary nature, for I am sick at heart of the business'.

"[31] In what may be the first review of Hawthorne's first novel, The Yankee referred to Fanshawe as "powerful and pathetic" and said that the author "should be encouraged to persevering efforts by a fair prospect of future success".

[39] These essays also offer unprecedented coverage of reproduction technology like engraving and lithography[40] and American portrait painters trained in the "humbler contingencies"[41] of sign painting and applied arts.

[42] The Yankee published his extensive coverage of art featured in The Token and The Atlantic Souvenir annual gift books,[43] which sometimes praised the engravers more than the painters.

[47] His serial essay "The Drama" (July–December 1829) elaborates upon opinions on theater originally published in the prefaces to his first play, Otho (1819) and his second poetry collection, The Battle of Niagara: Second Edition (1819).

[49] Neal predicted that characters would become more relatable by expressing feelings "in common language"[50] because "when a person talks beautifully in his sorrow, it shows both great preparation and insincerity.

"[52] This "thorough revolution in plays and players, authors and actors"[53] called for in "The Drama" was still in process 60 years later when William Dean Howells was considered innovative for issuing the same criticism.

[55] He published a "vigorous campaign" of seventeen articles against lotteries over the course of 1828, claiming they encourage idle and reckless behavior among patrons, an argument he first conveyed in his novel Logan (1822).

[57] In March 1828, Neal advertised his gymnasium in The Yankee as "accessible here to every body, without distinction of age or color",[58] but when he sponsored six Black men to join, only two other members of three hundred voted to accept them.

[70] Holding his native state in high regard, Neal in the third issue of The Yankee claimed: "Her magnitude, her resources, and her character, we believe, are neither appreciated nor understood by the chief men" and the "great mass of the American people.

[74] Described by one scholar as "vinegary",[75] the first volume of The Yankee (January 1 – December 24, 1828) documents literary feuds between Neal and other New England journalists like William Lloyd Garrison, Francis Ormand Jonathan Smith, and Joseph T.

[78] Journalist and historian Edward H. Elwell characterized Neal's willingness to publish these inflammatory back-and-forth letters and essays as the embodiment of "impulsive honesty and fair play".

[80] The Yankee published regularly from the beginning of 1828 through the end of 1829, during which time the magazine changed its name, printing format, frequency, and volume numbering system.