John, King of England

John died of dysentery contracted while on campaign in eastern England in late 1216; supporters of his son Henry III went on to achieve victory over Louis and the rebel barons the following year.

[5] These negative qualities provided extensive material for fiction writers in the Victorian era, and John remains a recurring character within Western popular culture, primarily as a villain in Robin Hood folklore.

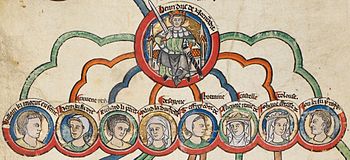

[10] The future of the empire upon Henry's eventual death was not secure: although the custom of primogeniture, under which an eldest son would inherit all his father's lands, was slowly becoming more widespread across Europe, it was less popular amongst the Norman kings of England.

[14] John was probably, like his brothers, assigned a magister whilst he was at Fontevrault, a teacher charged with his early education and with managing the servants of his immediate household; he was later taught by Ranulf de Glanvill, a leading English administrator.

[35] John was made Count of Mortain, was married to the wealthy Isabella of Gloucester, and was given valuable lands in Lancaster and the counties of Cornwall, Derby, Devon, Dorset, Nottingham and Somerset, all with the aim of buying his loyalty to Richard whilst the King was on crusade.

[51] Richard appears to have started to recognise John as his heir presumptive in the final years before his death, but the matter was not clear-cut and medieval law gave little guidance as to how the competing claims should be decided.

[61] Both sides paused for desultory negotiations before the war recommenced; John's position was now stronger, thanks to confirmation that the counts Baldwin IX of Flanders and Renaud of Boulogne had renewed the anti-French alliances they had previously agreed to with Richard.

[66][nb 5] Isabella of Angoulême, however, was already engaged to Hugh IX of Lusignan, an important member of a key Poitou noble family and brother of Raoul I, Count of Eu, who possessed lands along the sensitive eastern Normandy border.

[63] Just as John stood to benefit strategically from marrying Isabella, so the marriage threatened the interests of the Lusignans, whose own lands currently provided the key route for royal goods and troops across Aquitaine.

De Roches was a powerful Anjou noble, but John largely ignored him, causing considerable offence, whilst the King kept the rebel leaders in such bad conditions that twenty-two of them died.

[83] During the 12th century, there were contrary opinions expressed about the nature of kingship, and many contemporary writers believed that monarchs should rule in accordance with the custom and the law, and take counsel of the leading members of the realm.

[83] Modern historians remain divided as to whether John had a case of "royal schizophrenia" in his approach to government, or if his actions merely reflected the complex model of Angevin kingship in the early 13th century.

The Jews, who held a vulnerable position in medieval England, protected only by the King, were subject to huge taxes; £44,000 was extracted from the community by the tallage of 1210; much of it was passed on to the Christian debtors of Jewish moneylenders.

[121] De Braose was subjected to punitive demands for money, and when he refused to pay a huge sum of 40,000 marks (equivalent to £26,666 at the time),[nb 13] his wife, Maud, and one of their sons were imprisoned by John, which resulted in their deaths.

[20] Other historians have been more cautious in interpreting this material, noting that chroniclers also reported his personal interest in the life of St Wulfstan and his friendships with several senior clerics, most especially with Hugh of Lincoln, who was later declared a saint.

From the 1040s onwards, however, successive popes had put forward a reforming message that emphasised the importance of the Church being "governed more coherently and more hierarchically from the centre" and established "its own sphere of authority and jurisdiction, separate from and independent of that of the lay ruler", in the words of historian Richard Huscroft.

[183] John paid some of the compensation money he had promised the Church, but he ceased making payments in late 1214, leaving two-thirds of the sum unpaid; Innocent appears to have conveniently forgotten this debt for the good of the wider relationship.

[192] John's plan was to split Philip's forces by pushing north-east from Poitou towards Paris, whilst Otto, Renaud and Ferdinand, supported by William Longespée, marched south-west from Flanders.

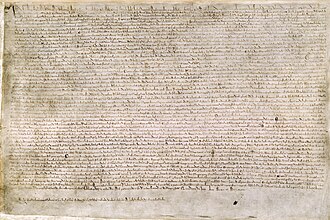

[202] The charter went beyond simply addressing specific baronial complaints, and formed a wider proposal for political reform, albeit one focusing on the rights of free men, not serfs and unfree labour.

He had stockpiled money to pay for mercenaries and ensured the support of the powerful marcher lords with their own feudal forces, such as William Marshal and Ranulf de Blondeville, 6th Earl of Chester.

[210] John's strategy was to isolate the rebel barons in London, protect his own supply lines to his key source of mercenaries in Flanders, prevent the French from landing in the south-east, and then win the war through slow attrition.

[222] Roger of Wendover provides the most graphic account of this, suggesting that the King's belongings, including the English Crown Jewels, were lost as he crossed one of the tidal estuaries which empties into the Wash, being sucked in by quicksand and whirlpools.

[230] Henry III continued his attempts to reclaim Normandy and Anjou until 1259, but John's continental losses and the consequent growth of Capetian power in the 13th century proved to mark a "turning point in European history".

[245] Historians in the "Whiggish" tradition, focusing on documents such as the Domesday Book and Magna Carta, trace a progressive and universalist course of political and economic development in England over the medieval period.

[250] Interpretations of Magna Carta and the role of the rebel barons in 1215 have been significantly revised: Although the charter's symbolic, constitutional value for later generations is unquestionable, in the context of John's reign, most historians now consider it a failed peace agreement between "partisan" factions.

[4] Jim Bradbury notes the current consensus that John was a "hard-working administrator, an able man, an able general", albeit, as Turner suggests, with "distasteful, even dangerous personality traits", including pettiness, spitefulness and cruelty.

[258] By contrast, Shakespeare's King John, a relatively anti-Catholic play that draws on The Troublesome Reign for its source material, offers a more "balanced, dual view of a complex monarch as both a proto-Protestant victim of Rome's machinations and as a weak, selfishly motivated ruler".

[259] Anthony Munday's play The Downfall and The Death of Robert Earl of Huntington portrays many of John's negative traits, but adopts a positive interpretation of the King's stand against the Roman Catholic Church, in line with the contemporary views of the Tudor monarchs.

[261] Nineteenth-century fictional depictions of John were heavily influenced by Sir Walter Scott's historical romance, Ivanhoe, which presented "an almost totally unfavourable picture" of the King; the work drew on 19th-century histories of the period and on Shakespeare's play.

[266] Popular works that depict John beyond the Robin Hood legends, such as James Goldman's play and later film, The Lion in Winter, set in 1183, commonly present him as an "effete weakling", in this instance contrasted with the more masculine Henry II, or as a tyrant, as in A.