Joseph Priestley and Dissent

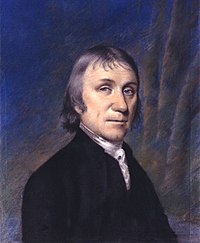

Joseph Priestley (13 March 1733 (old style) – 8 February 1804) was a British natural philosopher, political theorist, clergyman, theologian, and educator.

As the foremost British expounder of providentialism, he argued for extensive civil rights, believing that individuals could bring about progress and eventually the Millennium.

[2] Priestley's religious beliefs were integral to his metaphysics as well as his politics and he was the first philosopher to "attempt to combine theism, materialism, and determinism," a project that has been called "audacious and original.

[3][page needed] Between 1660 and 1665, Parliament passed a series of laws that restricted the rights of dissenters: they could not hold political office, teach school, serve in the military or attend Oxford and Cambridge unless they ascribed to the thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England.

Dissenters continually petitioned Parliament to repeal the Test and Corporation Acts, claiming that the laws made them second-class citizens.

[4] Priestley's friends urged him to publish a work on the injustices borne by Dissenters, a topic to which he had already alluded in his Essay on a Course of Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life (1765).

[11] In a statement that articulates key elements of early liberalism and anticipates utilitarian arguments, Priestley wrote: It must necessarily be understood, therefore, that all people live in society for their mutual advantage; so that the good and happiness of the members, that is the majority of the members of any state, is the great standard by which every thing relating to that state must finally be determined.

[15] Blackstone, chastened, replied in a pamphlet and altered his Commentaries in subsequent editions; he rephrased the offending passages but still described Dissent as a crime.

[21] He wrote numerous letters in defence of Unitarianism, in particular against certain ministers and scholars such as Samuel Horsley, Alexander Geddes, George Horne and Thomas Howes.

Although initially it looked as if they might succeed, by 1790, with the fears of the French Revolution looming in the minds of many members of Parliament, few were swayed by Charles James Fox's arguments for equal rights.

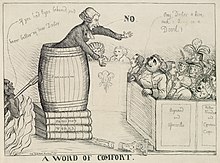

[24] In the midst of these trying times, it was the betrayal of William Pitt and Edmund Burke that most angered Priestley and his friends; they had expected the two men's support and instead both argued vociferously against the repeal.

[28] Priestley rushed to the defense of his friend and of the revolutionaries, publishing one of the many responses, along with Thomas Paine and Mary Wollstonecraft, that became part of the "Revolution Controversy."

[40] Priestley continued this series of arguments in The Doctrine of Philosophical Necessity Illustrated (1777);[41] the text was designed as an "appendix" to the Disquisitions and "suggests that materialism and determinism are mutually supporting.

"[42] Priestley explicitly stated that humans had no free will: "all things, past, present, and to come, are precisely what the Author of nature really intended them to be, and has made provision for.

"[43] His notion of "philosophical necessity," which he was the first to claim was consonant with Christianity, at times resembles absolute determinism; it is based on his understanding of the natural world and theology: like the rest of nature, man's mind is subject to the laws of causation, but because a benevolent God has created these laws, Priestley argued, the world as a whole will eventually be perfected.

[44] He argued that the associations made in a person's mind were a necessary product of their lived experience because Hartley's theory of associationism was analogous to natural laws such as gravity.

[46] In the last of his important books on metaphysics, Letters to a Philosophical Unbeliever (1780),[47] Priestley continues to defend his thesis that materialism and determinism can be reconciled with a belief in a God.

[49] The text addresses those whose faith is shaped by books and fashion; Priestley draws an analogy between the skepticism of educated men and the credulity of the masses.

"[50] In the three volumes, Priestley discusses, among many other works, Baron d'Holbach's Systeme de la Nature, often called the "bible of atheism."