Charles James Fox

Charles James Fox (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled The Honourable from 1762, was a British Whig politician and statesman whose parliamentary career spanned 38 years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Fox rose to prominence in the House of Commons as a forceful and eloquent speaker with a notorious and colourful private life, though at that time with rather conservative and conventional opinions.

Though Fox had little interest in the actual exercise of power[1] and spent almost the entirety of his political career in opposition, he became noted as an anti-slavery campaigner, a supporter of the French Revolution and a leading parliamentary advocate of religious tolerance and individual liberty.

[3] Fox was the darling of his father, who found Charles "infinitely engaging & clever & pretty" and, from the time that his son was three years old, apparently preferred his company at meals to that of anyone else.

[5] Given carte blanche to choose his own education, Fox in 1758 attended a fashionable Wandsworth school run by a Monsieur Pampellonne, followed by Eton College, where he began to develop his lifelong love of classical literature.

[3] Fox returned to Eton later that year, "attired in red-heeled shoes and Paris cut-velvet, adorned with a pigeon-wing hair style tinted with blue powder, and a newly acquired French accent", and was duly flogged by Dr. Barnard, the headmaster.

[3] On 28 December 1772, North appointed him to the board of the Treasury; in February 1774, Fox again surrendered his post, this time over the Government's allegedly feeble response to the contemptuous printing and public distribution of copies of parliamentary debates.

[3]Fox, who occasionally corresponded with Thomas Jefferson and had met Benjamin Franklin in Paris,[3] correctly predicted that Britain had little practical hope of subduing the colonies and interpreted the American cause approvingly as a struggle for liberty against the oppressive policies of a despotic and unaccountable executive.

"[14] Even after the Battle of Long Island in 1776, Fox stated that I hope that it will be a point of honour among us all to support the American pretensions in adversity as much as we did in their prosperity, and that we shall never desert those who have acted unsuccessfully upon Whig principles.

[15]On 31 October the same year, Fox responded to the King's address to Parliament with "one of his finest and most animated orations, and with severity to the answered person", so much so that, when he sat down, no member of the Government would attempt to reply.

[17] Fox thought that the motion is "glorious", saying on 24 April that: the question now was ... whether that beautiful fabric [i.e. the constitution] ... was to be maintained in that freedom ... for which blood had been spilt; or whether we were to submit to that system of despotism, which had so many advocates in this country.

[3] When North finally resigned under the strains of office and the disastrous American War in March 1782, after Earl Cornwallis surrendered at the Battle of Yorktown, and was gingerly replaced with the new ministry of the Marquess of Rockingham, Fox was appointed Foreign Secretary.

Based on this single conjunction of interests and the fading memory of the happy co-operation of the early 1770s, the two men who had vilified one another throughout the American war together formed a coalition and forced their Government, with an overwhelming majority composed of North's Tories and Fox's opposition Whigs, on to the King.

[25] George III now felt justified in dismissing Fox and North from government and in nominating Pitt the Younger in their place, the King appointed the youngest British prime minister to date at twenty-four years of age.

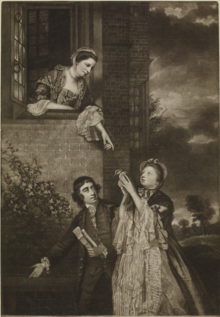

An energetic campaign in his favour was run by Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, allegedly a lover of Fox's who was said to have won at least one vote for him by kissing a shoemaker with a rather romantic idea of what constituted a bribe.

[28] One of Pitt's first major actions as prime minister was, in 1785, to put a scheme of parliamentary reform before the Commons, proposing to rationalise somewhat the existing, decidedly unrepresentative, electoral system by eliminating thirty-six rotten boroughs and redistributing seats to represent London and the larger counties.

[33] Thus the opportunity revealed itself for the establishment of a regency under Fox's friend and ally, the Prince of Wales, which would take the reins of government out of the hands of the incapacitated George III and allow the replacement of his "minion" Pitt with a Foxite ministry.

The king soon regained lucidity in time to prevent the establishment of his son's regency and the elevation of Fox to the premiership, and, on 23 April, a service of thanksgiving was conducted at St Paul's in honour of George III's return to health.

"[3] In April 1791, Fox told the Commons that he "admired the new constitution of France, considered altogether, as the most stupendous and glorious edifice of liberty, which had been erected on the foundation of human integrity in any time or country.

[40]Pitt, in turn, came to the defence of the Acts as adopted by the wisdom of our ancestors to serve as a bulwark to the Church, whose constituency was so intimately connected with that of the state, that the safety of the one was always liable to be affected by any danger which might threaten the other.

[3] On 18 April, Fox spoke in the Commons – together with William Wilberforce, Pitt and Burke – in favour of a measure to abolish the slave trade, but – despite their combined rhetorical talents – the vote went against them by a majority of 75.

[51] He argued against war measures like the stationing of Hessian troops in Britain, the employment of royalist French émigrés in the British army and, most of all, Pitt's suspension of habeas corpus in 1794.

[55] The distance from the stress and noise of Westminster was an enormous psychological and spiritual relief to Fox,[56] but still he defended his earlier principles: "It is a great comfort to me to reflect how steadily I have opposed this war, for the miseries it seems likely to produce are without end.

Having opposed the Addington ministry (though he approved of its negotiation of the Treaty of Amiens) as a Pitt-style tool of the King, Fox gravitated towards the Grenvillite faction, which shared his support for Catholic emancipation and composed the only parliamentary alternative to a coalition with the Pittites.

[59] Fox thought the coup d'état of 1799 that brought Napoleon to power "a very bad beginning ... the manner of the thing [was] quite odious",[60] but he was convinced that the French leader sincerely desired peace in order to consolidate his rule and rebuild his shattered country.

[citation needed] When Grenville formed a "Ministry of All the Talents" out of his supporters, the followers of Addington and the Foxites, Fox was once again offered the post of Foreign Secretary, which he accepted in February.

[71] To observers such as John Rickman, "Charley Fox eats his former opinions daily and even ostentatiously showing himself the worse man, but the better minister of a corrupt government", and who further claimed that "He should have died, for his fame, a little sooner; before Pitt".

[citation needed][73] Fox said that: So fully am I impressed with the vast importance and necessity of attaining what will be the object of my motion this night, that if, during the almost forty years that I have had the honour of a seat in parliament, I had been so fortunate as to accomplish that, and that only, I should think I had done enough, and could retire from public life with comfort, and the conscious satisfaction, that I had done my duty.

The King disliked Fox greatly, regarding him as beyond morality and the corrupter of his own eldest son, and the late eighteenth-century movements of Christian evangelism and middle-class 'respectability' also frowned on his excesses.

[86] Fox was the subject of the epigraph in John F. Kennedy's Pulitzer-prize winning book Profiles in Courage: "He well knows what snares are spread about his path, from personal animosity…and possibly from popular delusion.