Joseph Priestley

Joseph Priestley FRS (/ˈpriːstli/;[3] 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, Unitarian, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator and classical liberal political theorist.

[11] Priestley, who strongly believed in the free and open exchange of ideas, advocated toleration and equal rights for religious Dissenters, which also led him to help found Unitarianism in England.

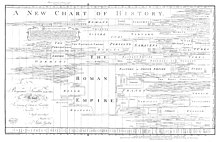

A scholar and teacher throughout his life, Priestley made significant contributions to pedagogy, including the publication of a seminal work on English grammar and books on history; he prepared some of the most influential early timelines.

Arguably his metaphysical works, however, had the most lasting influence, as now considered primary sources for utilitarianism by philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, and Herbert Spencer.

He was tutored by the Reverend George Haggerstone, who first introduced him to higher mathematics, natural philosophy, logic, and metaphysics through the works of Isaac Watts, Willem 's Gravesande, and John Locke.

[22] Priestley's Daventry friends helped him obtain another position and in 1758 he moved to Nantwich, Cheshire, living at Sweetbriar Hall in the town's Hospital Street; his time there was happier.

[25] In 1761, Priestley moved to Warrington in Cheshire and assumed the post of tutor of modern languages and rhetoric at the town's Dissenting academy, although he would have preferred to teach mathematics and natural philosophy.

Of his marriage, Priestley wrote: This proved a very suitable and happy connexion, my wife being a woman of an excellent understanding, much improved by reading, of great fortitude and strength of mind, and of a temper in the highest degree affectionate and generous; feeling strongly for others, and little for herself.

Also, greatly excelling in every thing relating to household affairs, she entirely relieved me of all concern of that kind, which allowed me to give all my time to the prosecution of my studies, and the other duties of my station.

Friends introduced him to the major experimenters in the field in Britain—John Canton, William Watson, Timothy Lane, and the visiting Benjamin Franklin who encouraged Priestley to perform the experiments he wanted to include in his history.

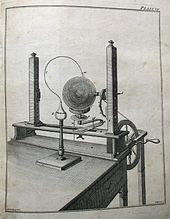

[52] Priestley's strength as a natural philosopher was qualitative rather than quantitative and his observation of "a current of real air" between two electrified points would later interest Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell as they investigated electromagnetism.

This work marked a change in Priestley's theological thinking that is critical to understanding his later writings—it paved the way for his materialism and necessitarianism (the latter being the belief that a divine being acts in accordance with necessary metaphysical laws).

[94] Maintaining that humans had no free will, Priestley argued that what he called "philosophical necessity" (akin to absolute determinism) is consonant with Christianity, a position based on his understanding of the natural world.

[112] Furthermore, the volumes were both a scientific and a political enterprise for Priestley, in which he argues that science could destroy "undue and usurped authority" and that government has "reason to tremble even at an air pump or an electrical machine".

Lavoisier's work began the long train of discovery that produced papers on oxygen respiration and culminated in the overthrow of phlogiston theory and the establishment of modern chemistry.

In December 2013, it was reported that Sir Christopher Bullock—a direct descendant of Shelburne's brother, Thomas Fitzmaurice (MP)—had married his wife, Lady Bullock, née Barbara May Lupton, at London's Unitarian Essex Church in 1917.

[127] Many of the friends that Priestley made in Birmingham were members of the Lunar Society, a group of manufacturers, inventors, and natural philosophers who assembled monthly to discuss their work.

"[135] Historian of science John McEvoy largely agrees, writing that Priestley's view of nature as coextensive with God and thus infinite, which encouraged him to focus on facts over hypotheses and theories, prompted him to reject Lavoisier's system.

[136] McEvoy argues that "Priestley's isolated and lonely opposition to the oxygen theory was a measure of his passionate concern for the principles of intellectual freedom, epistemic equality and critical inquiry.

In 1786, Priestley published its provocatively titled sequel, An History of Early Opinions concerning Jesus Christ, compiled from Original Writers, proving that the Christian Church was at first Unitarian.

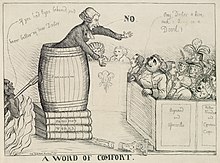

[143] In words that would boil over into a national debate, he challenged his readers to enact change: Let us not, therefore, be discouraged, though, for the present, we should see no great number of churches professedly unitarian .... We are, as it were, laying gunpowder, grain by grain, under the old building of error and superstition, which a single spark may hereafter inflame, so as to produce an instantaneous explosion; in consequence of which that edifice, the erection of which has been the work of ages, may be overturned in a moment, and so effectually as that the same foundation can never be built upon again ....[144] Although discouraged by friends from using such inflammatory language, Priestley refused to back down from his opinions in print and he included it, forever branding himself as "Gunpowder Joe".

When George III was eventually forced to send troops to the area, he said: "I cannot but feel better pleased that Priestley is the sufferer for the doctrines he and his party have instilled, and that the people see them in their true light.

Priestley there, patriot, and saint, and sage, Him, full of years, from his loved native land Statesmen blood-stained and priests idolatrous By dark lies maddening the blind multitude Drove with vain hate ....

[160] The couple's friends urged them to leave Britain and emigrate to either France or the new United States, even though Priestley had received an appointment to preach for the Gravel Pit Meeting congregation.

[citation needed] Since his arrival in America, Priestley had continued to defend his Christian Unitarian beliefs; now, falling increasingly under the influence of Thomas Cooper and Elizabeth Ryland-Priestley, he was unable to avoid becoming embroiled in political controversy.

In September 1799, William Cobbett printed extracts from this handbill, asserting that: "Dr Priestley has taken great pains to circulate this address, has travelled through the country for the purpose, and is in fact the patron of it."

[200] The 19th-century French naturalist George Cuvier, in his eulogy of Priestley, praised his discoveries while at the same time lamenting his refusal to abandon phlogiston theory, calling him "the father of modern chemistry [who] never acknowledged his daughter".

[204] A wide variety of philosophers, scientists, and poets became associationists as a result of his redaction of David Hartley's Observations on Man, including Erasmus Darwin, Coleridge, William Wordsworth, John Stuart Mill, Alexander Bain, and Herbert Spencer.

His scientific discoveries have usually been divorced from his theological and metaphysical publications to make an analysis of his life and writings easier, but this approach has been challenged recently by scholars such as John McEvoy and Robert Schofield.

[207] More recently, in 2001, historian of science Dan Eshet has argued that efforts to create a "synoptic view" have resulted only in a rationalisation of the contradictions in Priestley's thought, because they have been "organized around philosophical categories" and have "separate[d] the producers of scientific ideas from any social conflict".