Yugoslavia

It came into existence following World War I,[b] under the name of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes from the merger of the Kingdom of Serbia with the provisional State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, and constituted the first union of South Slavic peoples as a sovereign state, following centuries of foreign rule over the region under the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy.

[8][9] After an economic and political crisis and the rise of nationalism and ethnic conflicts following Tito's death, Yugoslavia broke up along its republics' borders during the Revolutions of 1989, at first into five countries, leading to the Yugoslav Wars.

[16] On 6 January 1929, King Alexander I got rid of the constitution, banned national political parties, assumed executive power, and renamed the country Yugoslavia.

[27] The international political scene in the late 1930s was marked by growing intolerance between the principal figures, by the aggressive attitude of the totalitarian regimes, and by the certainty that the order set up after World War I was losing its strongholds and its sponsors their strength.

Supported and pressured by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, Croatian leader Vladko Maček and his party managed the creation of the Banovina of Croatia (Autonomous Region with significant internal self-government) in 1939.

[citation needed] Prince Paul submitted to fascist pressure and signed the Tripartite Pact in Vienna on 25 March 1941, hoping to continue keeping Yugoslavia out of the war.

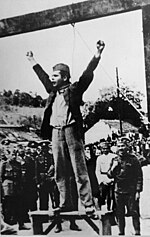

On 17 April, representatives of Yugoslavia's various regions signed an armistice with Germany in Belgrade, ending eleven days of resistance against the invading German forces.

The Chetniks were initially supported by the exiled royal government and the Allies, but they soon focused increasingly on combating the Partisans rather than the occupying Axis forces.

In May 1945, the Partisans met with Allied forces outside former Yugoslav borders, after also taking over Trieste and parts of the southern Austrian provinces of Styria and Carinthia.

[39] Western attempts to reunite the Partisans, who denied the supremacy of the old government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and the émigrés loyal to the king led to the Tito-Šubašić Agreement in June 1944; however, Marshal Josip Broz Tito was in control and was determined to lead an independent communist state, starting as a prime minister.

[42] On 11 November 1945, parliamentary elections were held with only the Communist-led People's Front appearing on the ballot, securing all 354 seats in the newly formed Constituent Assembly.

[citation needed] First cracks in the tightly governed system surfaced when students in Belgrade and several other cities joined the worldwide protests of 1968.

[59] Tito, whose home republic was Croatia, was concerned over the stability of the country and responded in a manner to appease both Croats and Serbs: he ordered the arrest of the Croatian Spring protestors while at the same time conceding to some of their demands.

Albanian and Hungarian became nationally recognised minority languages, and the Serbo-Croat of Bosnia and Montenegro altered to a form based on the speech of the local people and not on the standards of Zagreb and Belgrade.

In other words, in less than two years "the trigger mechanism" (under the Financial Operations Act) had led to the layoff of more than 600,000 workers out of a total industrial workforce of the order of 2.7 million.

[68] In 1986, the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts drafted a memorandum addressing some burning issues concerning the position of Serbs as the most numerous people in Yugoslavia.

Through a series of moves known as the "anti-bureaucratic revolution", Milošević succeeded in reducing the autonomy of Vojvodina and of Kosovo and Metohija,[70] but both entities retained a vote in the Yugoslav Presidency Council.

[75][76] The constitutional crisis that inevitably followed resulted in a rise of nationalism in all republics: Slovenia and Croatia voiced demands for looser ties within the federation.

[citation needed] Slovenia and Croatia elected governments oriented towards greater autonomy of the republics (under Milan Kučan and Franjo Tuđman, respectively).

The results of all these conflicts were the almost total emigration of the Serbs from all three regions, the massive displacement of the populations in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the establishment of the three new independent states.

[citation needed] Serbian uprisings in Croatia began in August 1990 by blocking roads leading from the Dalmatian coast towards the interior almost a year before Croatian leadership made any move towards independence.

These activities were under constant surveillance and produced a video of a secret meeting between the Croatian Defence minister Martin Špegelj and two unidentified men.

[citation needed] On 9 March 1991, demonstrations were held against Slobodan Milošević in Belgrade, but the police and the military were deployed in the streets to restore order, killing two people.

The Yugoslav People's Army (JNA), whose superior officers were mainly of Serbian ethnicity, maintained an impression of being neutral, but as time went on, they became increasingly more involved in state politics.

The following day (26 June), the Federal Executive Council specifically ordered the army to take control of the "internationally recognized borders", leading to the Ten-Day War.

The Austrian ORF TV network showed footage of three Yugoslav Army soldiers surrendering to the territorial defence force when gunfire was heard and the troops were seen falling down.

According to the Brioni Agreement, recognised by representatives of all republics, the international community pressured Slovenia and Croatia to place a three-month moratorium on their independence.

[69] Eventually, after the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević from power as president of the federation in 2000, the country dropped those aspirations, accepted the opinion of the Badinter Arbitration Committee about shared succession, and reapplied for and gained UN membership on 2 November 2000.

[97] Likewise, the Serbian Orthodox Church received favorable treatment, and Yugoslavia did not engage in anti-religious campaigns to the extent of other countries in the Eastern Bloc.

[99] Religious differences between Orthodox Serbs and Macedonians, Catholic Croats and Slovenes, and Muslim Bosniaks and Albanians alongside the rise of nationalism contributed to the collapse of Yugoslavia in 1991.