Julian's Persian expedition

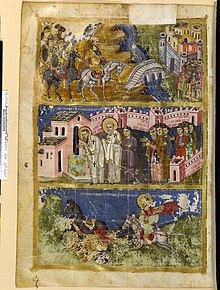

In order to mislead the opponent and to carry out a pincer attack, he sent a detachment to join with his ally Arshak II of Arsacid Armenia to take the Tigris route from the north.

Julian died of wounds from one of these skirmishes and his successor, Jovian, agreed to surrender under unfavorable terms in order to save the remnants of his demoralized and exhausted army from annihilation.

[9] According to Ammianus Marcellinus, Julian's aim was to enhance his fame as a general and to punish the Persians for their invasions of Rome's eastern provinces; for this reason, he refused Shapur's immediate offer of negotiations.

[14] He instructed Arshak II of Armenia to prepare a large army, but without revealing its purpose;[15] he sent Lucillianus to Samosata in the upper Euphrates valley to build a fleet of river ships.

[18] The whole army mustered there, crossed the middle Euphrates and proceeded to Carrhae (Harran), the site of the famous battle in which the Roman general Crassus was defeated and killed in 53 BC.

Many modern scholars have praised the choice of routes, rapid movements, and deception, while some consider the plan to be inadequate with regard to supply, communication, climate consideration, and the difficulty of crossing between Euphrates and Tigris near Naarmalcha.

[9] Julian himself, with the larger part of his army of 65,000, of which it is unclear whether that was before or after Procopius' departure, turned south along the Balikh River towards the lower Euphrates, reaching Callinicum (al-Raqqah) on 27 March and meeting the fleet of 1,100 supply vessels and 50 armed galleys under the command of Lucillianus.

[24] The army followed the Euphrates downstream to the border city of Circesium and crossed the river Aboras (Khabur) with the help of a pontoon bridge constructed for the purpose.

[9] Once over the border, Julian invigorated the soldiers' ardor with a fiery oration, representing his hopes and reasons for the war, and distributed a donative of 130 pieces of silver to each.

[9] After destroying the private residence, palaces, gardens and extensive menagerie of the Persian monarchy north of Ctesiphon, and securing his position by improvised fortifications, Julian turned his attention to the city itself.

In order to invest the place on both sides, Julian first dug a canal between the Euphrates and Tigris, allowing his fleet to enter the latter river, and by this means ferried his army to the further bank.

But in the contest victory lay ultimately with the Romans, and the Persians were driven back within the city walls after sustaining losses of twenty-five hundred men; Julian's casualties are given at no more than 70.

[33] Although ancient and modern historians have censured the rashness of the deed, Edward Gibbon palliates the folly by observing that Julian expected a plentiful supply from the harvests of the fertile territory by which he was to march, and, with regard to the fleet, that it was not navigable up the river, and must be taken by the Persians if abandoned intact.

Meanwhile, if he retreated northward with the entire army immediately, his already considerable achievements would be undone, and his prestige irreparably damaged, as one who had obtained success by stratagem and fled upon the resurgence of the foe.

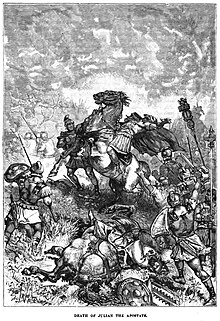

Before the attack could be repelled, a warning from the vanguard revealed that the army was surrounded in an ambush, the Persians having stolen a march to occupy the Roman route ahead.

While the army struggled to form up so as to meet the manifold threats from every side, a charge of elephants and cavalry rattled the Roman line on the left, and Julian, to prevent its imminent collapse, led his reserves in-person to shore up the defense.

The light infantry under his command overthrew the massive troops of Persian heavy cavalry and elephants, and Julian, by the admission of the most hostile authorities, proved his courage in the conduct of the attack.

[37] That midnight Julian died in his tent; "Having received from the Deity", in his own words to the assembled officers, "in the midst of an honorable career, a splendid and glorious departure from the world.

The Persians, revived by the intelligence of their conqueror's demise, fell twice on the rear of the retreat, and on the camp, one party penetrating to the imperial tent before being cut off and destroyed at Jovian's feet.

At Dura on the fourth day the army came to a halt, deluded with the vain hope of bridging the river with makeshift contraptions of timber and animal hide.

Meanwhile, Jovian's supplies and expedients were depleted, and in his overwhelming joy at the prospect of saving his army, his fortunes, and the empire which he later gained, he was willing to overlook the excessive harshness of the terms, and subscribe his signature to the Imperial disgrace along with the demands of Shapur II.

Notwithstanding the entreaties of the populace, and those of the remainder of the territories ceded to Shapur, as also the gossip and calumnies of the Roman people, Jovian conformed to his oath; the depopulated were resettled in Amida, funds for the restoration of which were granted lavishly by the emperor.

[45][better source needed] From Nisibis Jovian proceeded to Antioch, where the insults of the citizenry at his cowardice soon drove the disgusted emperor to seek a more hospitable place of abode.

[46] Notwithstanding widespread disaffection at the shameful accommodation which he had made, the Roman world accepted his sovereignty; the deputies of the western army met him at Tyana, on his way to Constantinople, where they rendered him homage.

From Antioch he issued decrees immediately repealing the hostile edicts of Julian, which forbade the Christians from the teaching of secular studies, and unofficially banned them from employment in the administration of the state.

At the same time, while Jovian expressed the hope that all his subjects would embrace the Christian religion, he granted the rights of conscience to all of mankind, leaving the pagans free to worship in their temples (barring only certain rites which previously had been suppressed), and freedom from persecution to the Jews.