Battle of Strasbourg

The Franks and Alamanni on the Rhine frontier now seized the opportunity presented by the absence of the best Roman forces in the civil war to overrun much of eastern Gaul and Raetia.

[19] The barbarians captured many of the Roman forts along the Rhine, demolished their fortifications, and established permanent camps on the West bank of the river, which they used as bases to pillage Gaul during the four years that the civil war lasted (350–3).

This was a difficult decision for a paranoid ruler who regarded all his relatives with intense suspicion and had already put to death 2 of his uncles and 7 cousins, including Julian's half-brother Constantius Gallus.

[25] The appointment, though greeted with enthusiasm by the troops at Milan, was more generally seen as unsuitable as Julian, who was just 23 years old, had no military experience and until that moment had spent his time studying philosophy at Athens.

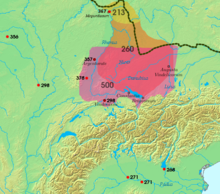

According to Ammianus, Mogontiacum (Mainz), Borbetomagus (Worms), Nemetae Vangionum (Speyer), Tabernae (Saverne), Saliso (Seltz), and Argentorate (Strasbourg) were all in German hands.

[30] Further, the Roman limitanei (border defence forces) along the Rhine had been decimated by the fall of most of their forts to the Germans, while those units that survived intact had mostly retreated from the frontier to garrison Gaul's cities.

[34] En route to Gaul from Milan, at Taurini (Turin), he received the calamitous news that Cologne, Rome's most important city and military fortress on the Rhine, had fallen to the Franks.

For the 356 campaigning season, Julian's first task was to link up with the main Gaul comitatus, which had wintered at Remi (Reims) under the command of the magister equitum, Ursicinus' recently appointed successor, Marcellus.

[36] At Reims, Julian showed his characteristic boldness by deciding, in conference with his senior commanders, to deal with the Alamanni problem at the source by marching straight to Alsace and restoring Roman control of the region.

[37] On the way, however, his army was ambushed and nearly destroyed at Decem Pagi (Dieuze) by a large German band who fell on two rearguard legions which had lost contact with the rest of the column in dense mist.

[43] But large bands of Alamanni, ignoring the threat posed by the Roman manoeuvre, invaded and ravaged the rich Rhone valley, even trying to take the major city of Lugdunum (Lyon) by assault.

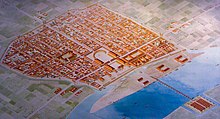

Saverne lay astride the Mediomatrici (Metz) – Strasbourg Roman highway, at the mouth of the main entry route through the Vosges mountains into northern Alsace, a location with commanding heights overlooking the Rhine valley.

The vanguard fled in disarray, and instead of engaging, Barbatio led the rest of his force in a hasty retreat, under close pursuit by the Germans, out of Alsace and a good way into Raetia, in the process losing most of his sutlers, pack animals, and baggage.

[53] This figure may be an exaggeration, but the exceptional size of the levy is shown by the presence of all the Alamanni kings and the report of a captured scout that the Germans took three entire days in crossing the Rhine by the bridge at Strasbourg.

[Note 1] Another possible indicator of Chnodomar's numbers is size of forces considered necessary by the Roman government to deal with the Alamanni threat in Gaul: 40,000 (Julian's 15,000 plus Barbatio's 25,000).

According to Ammianus, they had to rely on a concentrated frontal charge to try to break through by weight of numbers, and proved no match for the Romans in the final phase of the battle, a prolonged struggle of attrition at close-quarters.

For short-range missile (throwing) weapons, a Roman infantryman would probably had either a long throwing-spear or two or three short javelins (lanceae) and half a dozen plumbatae (weighted darts) with an effective range of about 30m.

[32] Ammianus talks of a variety of missiles being thrown by the Alamanni in the battle: spicula (a kind of long pilum-type javelin, also known as an angon), verruta missilia (short throwing-spears) and ferratae arundines (probably darts and franciscas: throwing-axes).

It appears that Julian's army set forth at dawn, and apparently arrived within sight of the barbarian entrenchments (vallum) outside Strasbourg at around midday, after a march of 21 Roman miles.

[71] Set back from the left flank of the front line, Julian posted a separate division under Severus to face the woods beyond the highway, apparently with orders to advance into them, presumably to launch a surprise attack on the German right wing.

Failing a cavalry breakthrough, Julian would have to rely on a struggle of attrition on foot, in which superior Roman armour, training, and formation discipline would almost inevitably prevail.

But the serried ranks of the Roman front, shields massed together “as in a testudo” held them off for a long time, inflicting severe casualties on the Germans who flung themselves recklessly at their bristling spears.

[69] Chnodomar himself and his retinue tried to escape on horseback, hoping to reach some boats prepared for just such an emergency near the ruined Roman fort of Concordia (Lauterbourg), some 40 km downstream from Strasbourg.

The immediate aftermath of the battle saw a vigorous "ethnic cleansing" campaign as all Alamanni families who had settled in Alsace on stolen land were rounded up and expelled from imperial territory.

Until then, Julian was obliged to campaign largely inside Gaul, with the barbarian bands holding the initiative, playing cat-and-mouse with his forces and causing enormous economic damage to a vital region of the empire.

[126] In 359, Julian restored seven forts and town walls in the middle Rhine, including Bonna (Bonn) and Bingium (Bingen), obliging his new tributary Alamanni to provide the supplies and labour needed.

[127] By 360, Gaul was sufficiently secure to permit Julian to despatch reinforcements of about 3,000 men under magister armorum Lupicinus to Britain, which had suffered a serious land and sea invasion by the Picts of Caledonia (Scotland) and the Scoti of Hibernia (Ireland).

[63] But at the same time, Julian received a demand from Constantius, who was unaware of the British expedition, that he send 4 auxilia palatina regiments plus select squadrons of cavalry (about 2,500 men) under Lupicinus to the East as reinforcements for the war against the Persians.

Alarmed, but also secretly pleased, Julian accepted the title and wrote an apologetic letter to Constantius explaining why he had felt it necessary to bow to his soldiers' wishes and requesting his ratification.

As sole emperor (361–3), Julian succumbed, as many Roman leaders before him (e.g. Crassus, Trajan, Septimius Severus) to "Alexander the Great syndrome": the desire to emulate the Macedonian general and conquer the Persian empire.