Jurin's law

Jurin's law, or capillary rise, is the simplest analysis of capillary action—the induced motion of liquids in small channels[1]—and states that the maximum height of a liquid in a capillary tube is inversely proportional to the tube's diameter.

Capillary action is one of the most common fluid mechanical effects explored in the field of microfluidics.

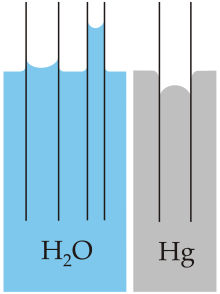

The difference in height between the surroundings of the tube and the inside, as well as the shape of the meniscus, are caused by capillary action.

The mathematical expression of this law can be derived directly from hydrostatic principles and the Young–Laplace equation.

Jurin's law allows the measurement of the surface tension of a liquid and can be used to derive the capillary length.

[3] The law is expressed as[citation needed] where It is only valid if the tube is cylindrical and has a radius (r0) smaller than the capillary length (

In terms of the capillary length, the law can be written as For a water-filled glass tube in air at standard conditions for temperature and pressure, γ = 0.0728 N/m at 20 °C, ρ = 1000 kg/m3, and g = 9.81 m/s2.

Because water spreads on clean glass, the effective equilibrium contact angle is approximately zero.

[4] For these values, the height of the water column is Thus for a 2 m (6.6 ft) radius glass tube in lab conditions given above, the water would rise an unnoticeable 0.007 mm (0.00028 in).

Capillary action is used by many plants to bring up water from the soil.

During the 15th century, Leonardo da Vinci was one of the first to propose that mountain streams could result from the rise of water through small capillary cracks.

[3][6] It is later, in the 17th century, that the theories about the origin of capillary action begin to appear.

Jacques Rohault erroneously supposed that the rise of the liquid in a capillary could be due to the suppression of air inside and the creation of a vacuum.

The astronomer Geminiano Montanari was one of the first to compare the capillary action to the circulation of sap in plants.

Additionally, the experiments of Giovanni Alfonso Borelli determined in 1670 that the height of the rise was inversely proportional to the radius of the tube.

Francis Hauksbee, in 1713, refuted the theory of Rohault through a series of experiments on capillary action, a phenomenon that was observable in air as well as in vacuum.

Hauksbee also demonstrated that the liquid rise appeared on different geometries (not only circular cross sections), and on different liquids and tube materials, and showed that there was no dependence on the thickness of the tube walls.

Isaac Newton reported the experiments of Hauskbee in his work Opticks but without attribution.

[3][6] It was the English physiologist James Jurin, who finally in 1718[2] confirmed the experiments of Borelli and the law was named in his honour.

of the liquid column in the tube is constrained by the hydrostatic pressure and by the surface tension.

The following derivation is for a liquid that rises in the tube; for the opposite case when the liquid is below the reference level, the derivation is analogous but pressure differences may change sign.

At the meniscus interface, due to the surface tension, there is a pressure difference of

, and the meniscus has a spherical shape, the radius of curvature is

Outside and far from the tube, the liquid reaches a ground level in contact with the atmosphere.

Liquids in communicating vessels have the same pressures at the same heights, so a point

, inside the tube, at the same liquid level as outside, would have the same pressure