Contact angle

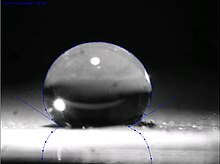

A given system of solid, liquid, and vapor at a given temperature and pressure has a unique equilibrium contact angle.

The equilibrium contact angle reflects the relative strength of the liquid, solid, and vapour molecular interaction.

[2] A century later Gibbs[3] proposed a modification to Young's equation to account for the volumetric dependence of the contact angle.

Gibbs postulated the existence of a line tension, which acts at the three-phase boundary and accounts for the excess energy at the confluence of the solid-liquid-gas phase interface, and is given as:

Although experimental data validates an affine relationship between the cosine of the contact angle and the inverse line radius, it does not account for the correct sign of κ and overestimates its value by several orders of magnitude.

Jasper[5][4] proposed that including a V dP term in the variation of the free energy may be the key to solving the contact angle problem at such small scales.

The advancing and receding contact angles are measured from dynamic experiments where droplets or liquid bridges are in movement.

[1] In contrast, the equilibrium contact angle described by the Young-Laplace equation is measured from a static state.

The overall effect can be seen as closely analogous to static friction, i.e., a minimal amount of work per unit distance is required to move the contact line.

Advancing and receding contact angle measurements can be carried out by adding and removing liquid from a drop deposited on a surface.

Real surfaces are not atomically smooth or chemically homogeneous so a drop will assume contact angle hysteresis.

The equilibrium contact angle (θC) can be calculated from θA and θR as was shown theoretically by Tadmor[7] and confirmed experimentally by Chibowski[8] as,

The discrepancies between static and dynamic contact angles are closely proportional to the capillary number, noted

This is due to the mean curvature term which includes products of first- and second-order derivatives of the drop shape function

Solving this elliptic partial differential equation that governs the shape of a three-dimensional drop, in conjunction with appropriate boundary conditions, is complicated, and an alternate energy minimization approach to this is generally adopted.

The shapes of three-dimensional sessile and pendant drops have been successfully predicted using this energy minimisation method.

[14] Contact angles are extremely sensitive to contamination; values reproducible to better than a few degrees are generally only obtained under laboratory conditions with purified liquids and very clean solid surfaces.

[15] Some materials with highly rough surfaces may have a water contact angle even greater than 150°, due to the presence of air pockets under the liquid drop.

Contact angles are equally applicable to the interface of two liquids, though they are more commonly measured in solid products such as non-stick pans and waterproof fabrics.

Control of the wetting contact angle can often be achieved through the deposition or incorporation of various organic and inorganic molecules onto the surface.

With the proper selection of the organic molecules with varying molecular structures and amounts of hydrocarbon and/or perfluorinated terminations, the contact angle of the surface can tune.

The deposition of these specialty silanes[17] can be achieved in the gas phase through the use of a specialized vacuum ovens or liquid-phase process.

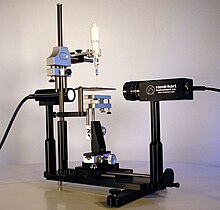

Current-generation systems employ high resolution cameras and software to capture and analyze the contact angle.

Experimental apparatus to measure pendant drop contact angles on inclined substrates has been developed recently.

[20] This method allows for the deposition of multiple microdrops on the underside of a textured substrate, which can be imaged using a high resolution CCD camera.

An automated system allows for tilting the substrate and analysing the images for the calculation of advancing and receding contact angles.

Also in that case it is possible to measure the equilibrium contact angle by applying a very controlled vibration.

[21] Dynamic Wilhelmy method applied to single fibers to measure advancing and receding contact angles.

Instead of measuring with a balance, the shape of the meniscus on the fiber is directly imaged using a high resolution camera.

Automated meniscus shape fitting can then directly measure the static, advancing or receding contact angle on the fiber.