Kansai dialect

For example, chigau (to be different or wrong) becomes chau, yoku (well) becomes yō, and omoshiroi (interesting or funny) becomes omoroi.

This particular verb is a dead giveaway of a native Kansai speaker, as most will unconsciously say 言うて /juːte/ instead of 言って /iQte/ or /juQte/ even if well-practiced at speaking in standard Japanese.

Other examples of geminate replacement are 笑った /waraQta/ ("laughed") becoming 笑うた /waroːta/ or わろた /warota/ and 貰った /moraQta/ ("received") becoming 貰うた /moroːta/, もろた /morota/ or even もうた /moːta/.

The potential verb endings /-eru/ for 五段 godan and -られる /-rareru/ for 一段 ichidan, recently often shortened -れる /-reru/ (ra-nuki kotoba), are common between the standard Japanese and Kansai dialect.

However, mainly in Osaka, potential negative form of 五段 godan verbs /-enai/ is often replaced with /-areheN/ such as 行かれへん /ikareheN/ instead of 行けない /ikenai/ and 行けへん /ikeheN/ "can't go".

In Osaka, Kyoto, Shiga, northern Nara and parts of Mie, mainly in masculine speech, -よる /-joru/ shows annoying or contempt feelings for a third party, usually milder than -やがる /-jaɡaru/.

The stem of adjective forms in Kansai dialect is generally the same as in standard Japanese, except for regional vocabulary differences.

Dropping the consonant from the final mora in all forms of adjective endings has been a frequent occurrence in Japanese over the centuries (and is the origin of such forms as ありがとう /ariɡatoː/ and おめでとう /omedetoː/), but the Kantō speech preserved く /-ku/ while reducing し /-si/ and き /-ki/ to /-i/, thus accounting for the discrepancy in the standard language (see also Onbin) The /-i/ ending can be dropped and the last vowel of the adjective's stem can be stretched out for a second mora, sometimes with a tonal change for emphasis.

Polite suffixes です/だす/どす /desu, dasu, dosu/ and ます /-masu/ are also added やろ /jaro/ for presumptive form instead of でしょう /desjoː/ in standard Japanese.

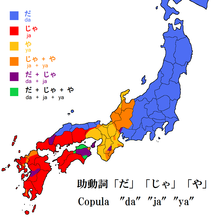

Ya originated from ja (a variation of dearu) in late Edo period and is still commonly used in other parts of western Japan like Hiroshima, and is also used stereotypically by old men in fiction.

When some sentence-final particles and a presumptive inflection yaro follow -su ending polite forms, su is often combined especially in Osaka.

Even today, keigo is used more often in Kansai than in the other dialects except for the standard Japanese, to which people switch in formal situations.

The interjectory particle (間投助詞, kantō-joshi) na or naa is used very often in Kansai dialect instead of ne or nee in standard Japanese.

It is not only used as interjectory particle (as emphasis for the imperative form, expression an admiration, and address to listeners, for example), and the meaning varies depending on context and voice intonation, so much so that naa is called the world's third most difficult word to translate.

In western Japanese including Kansai dialect, however, it is used equally by both men and women in many different levels of conversation.

In some areas such as Kawachi and Banshu, ke is used instead of ka, but it is considered a harsh masculine particle in common Kansai dialect.

These variations are now archaic, but are still widely used in fictitious creations to represent stereotypical Kansai speakers especially wate and wai.

Jibun (自分) is a Japanese word meaning "oneself" and sometimes "I", but it has an additional usage in Kansai as a casual second-person pronoun.

In traditional Kansai dialect, the honorific suffix -san is sometimes pronounced -han when -san follows a, e and o; for example, okaasan ("mother") becomes okaahan, and Satō-san ("Mr. Satō") becomes Satō-han.

The suffix -san is also added to some familiar greeting phrases; for example, ohayō-san ("good morning") and omedetō-san ("congratulations").

[10] In the Edo period, Senba-kotoba (船場言葉), a social dialect of the wealthy merchants in the central business district of Osaka, was considered the standard Osaka-ben.

It was characterized by the polite speech based on Kyoto-ben and the subtle differences depending on the business type, class, post etc.

It was handed down in Meiji, Taishō and Shōwa periods with some changes, but after the Pacific War, Senba-kotoba became nearly an obsolete dialect due to the modernization of business practices.

Southern branches of Osaka-ben, such as Senshū-ben (泉州弁) and Kawachi-ben (河内弁), are famous for their harsh locution, characterized by trilled "r", the question particle ke, and the second person ware.

The farther south in Osaka one goes, the cruder the language is considered to be, with the local Senshū-ben of Kishiwada said to represent the peak of harshness.

The latter has subtle difference at each social class such as old merchant families at Nakagyo, craftsmen at Nishijin and geiko at Hanamachi (Gion, Miyagawa-chō etc.)

For example, the copula da, the Tokyo-type accent, the honorific verb ending -naru instead of -haru and the peculiarly diphthong [æː] such as [akæː] for akai "red".

As mentioned above, Tajima-ben (但馬弁) spoken in northern Hyōgo, former Tajima Province, is included in Chūgoku dialect as well as Tango-ben.

Shiga Prefecture is the eastern neighbor of Kyoto, so its dialect, sometimes called Shiga-ben (滋賀弁) or Ōmi-ben (近江弁) or Gōshū-ben (江州弁), is similar in many ways to Kyoto-ben.

The southern dialect uses Tokyo type accent, has the discrimination of grammatical aspect, and does not show a tendency to lengthen vowels at the end of monomoraic nouns.