Karma in Jainism

Karma not only encompasses the causality of transmigration, but is also conceived of as an extremely subtle matter, which infiltrates the soul—obscuring its natural, transparent and pure qualities.

The Jain karmic theory attaches great responsibility to individual actions, and eliminates any reliance on some supposed existence of divine grace or retribution.

[3] Over the centuries, Jain monks have developed a large and sophisticated corpus of literature describing the nature of the soul, various aspects of the working of karma, and the ways and means of attaining mokṣa.

[4] Jainism speaks of karmic "dirt", as karma is thought to be manifest as very subtle and sensually imperceptible particles pervading the entire universe.

[10] In the same manner, consequences occur naturally when one utters a lie, steals something, commits senseless violence or leads a life of debauchery.

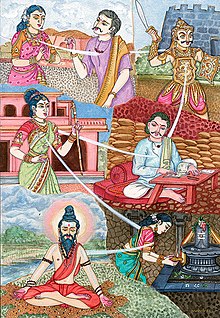

Paul Dundas notes that the ascetics often used cautionary tales to underline the full karmic implications of morally incorrect modes of life, or excessively intense emotional relationships.

[17] Jain texts narrate how even Māhavīra, one of the most popular propagators of Jainism and the 24th tīrthaṇkara (ford-maker),[note 4] had to bear the brunt of his previous karma before attaining kevala jñāna.

[18] The Ācāranga Sūtra speaks of how Māhavīra bore his karma with complete equanimity, as follows:[19] He was struck with a stick, the fist, a lance, hit with a fruit, a clod, a potsherd.

Throwing him up they let him fall, or disturbed him in his religious postures; abandoning the care of his body, the Venerable One humbled himself and bore pain, free from desires.

Bearing all hardships, the Venerable One, undisturbed, proceeded on the road to nirvāṇa.Karma forms a central and fundamental part of Jain faith, being intricately connected to other of its philosophical concepts like transmigration, reincarnation, liberation, non-violence (ahiṃsā) and non-attachment, among others.

Kindness, compassion and humble character result in human birth; while austerities and the making and keeping of vows leads to rebirth in heaven.

[25] There are five types of bodies in the Jain thought: earthly (e.g. most humans, animals and plants), metamorphic (e.g. gods, hell beings, fine matter, some animals and a few humans who can morph because of their perfections), transference type (e.g. good and pure substances realized by ascetics), fiery (e.g. heat that transforms or digests food), and karmic (the substrate where the karmic particles reside and which make the soul ever changing).

[33] According to the Jain theory of karma, the karmic matter imparts a colour (leśyā) to the soul, depending on the mental activities behind an action.

In the same way, the soul also reflects the qualities of taste, smell and touch of associated karmic matter, although it is usually the colour that is referred to when discussing the leśyās.

This is explained by Kundakunda (1st Century CE) in Samayasāra 262–263: "The intent to kill, to steal, to be unchaste and to acquire property, whether these offences are actually carried or not, leads to bondage of evil karmas.

[44] This is supported by the fact that both Svetambara and Digambara sects agree on the basic doctrine, giving indication that it reached in its present form before the schism took place.

Perhaps the entire concept that a person's situation and experiences are in fact the results of deeds committed in various lives may not be Aryan origin at all, but rather may have developed as a part of the indigenous Gangetic traditions from which the various Sramana movements arose.

In addition to śrāddha (the Hindu ritual of offering to the dead ancestors), we find among Hindus widespread adherence to the notion of divine intervention in one's fate, while (Mahayana) Buddhists eventually came to propound such theories like boon-granting Bodhisattvas, transfer of merit and like.

Duration and intensity of the karmic bond are determined by emotions or "kaṣāya" and type and quantity of the karmas bound is depended on yoga or activity.

[6] The passions like anger, pride, deceit and greed are called sticky (kaṣāyas) because they act like glue in making karmic particles stick to the soul resulting in bandha.

[61] Hence the ancient Jain texts talk of subduing these negative emotions:[62] When he wishes that which is good for him, he should get rid of the four faults—anger, pride, deceit and greed—which increase the evil.

When different permutations of the sub-elements of the four factors are calculated, the Jain teachers speak of 108 ways in which the karmic matter can be attracted to the soul.

A great part of attracted karma bears its consequences with minor fleeting effects, as generally most of our activities are influenced by mild negative emotions.

[85] Justice Tukol notes that the supreme importance of the doctrine of karma lies in providing a rational and satisfying explanation to the apparent unexplainable phenomenon of birth and death, of happiness and misery, of inequalities and of existence of different species of living beings.

The theory of karma is able to explain day-to-day observable phenomena such as inequality between the rich and the poor, luck, differences in lifespan, and the ability to enjoy life despite being immoral.

In particular, Vedanta Hindus considered the Jain position on the supremacy and potency of karma, specifically its insistence on non-intervention by any Supreme Being in regard to the fate of souls, as nāstika or atheistic.

[89] For example, in a commentary to the Brahma Sutras (III, 2, 38, and 41), Adi Sankara, argues that the original karmic actions themselves cannot bring about the proper results at some future time; neither can super sensuous, non-intelligent qualities like adrsta—an unseen force being the metaphysical link between work and its result—by themselves mediate the appropriate, justly deserved pleasure and pain.

"[91] In another Buddhist text Majjhima Nikāya, the Buddha criticizes Jain emphasis on the destruction of unobservable and unverifiable types of karma as a means to end suffering, rather than on eliminating evil mental states such as greed, hatred and delusion, which are observable and verifiable.

According to Jainism, nigodas are lowest form of extremely microscopic beings having momentary life spans, living in colonies and pervading the entire universe.

However, as Paul Dundas puts it, the Jain theory of karma does not imply lack of free will or operation of total deterministic control over destinies.