Johannes Kepler

[21] Kepler was born on 27 December 1571, in the Free Imperial City of Weil der Stadt (now part of the Stuttgart Region in the German state of Baden-Württemberg).

[29] Before concluding his studies at Tübingen, Kepler accepted an offer to teach mathematics as a replacement to Georg Stadius at the Protestant school in Graz (now in Styria, Austria).

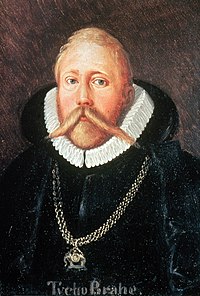

[34] He also sought the opinions of many of the astronomers to whom he had sent Mysterium, among them Reimarus Ursus (Nicolaus Reimers Bär)—the imperial mathematician to Rudolf II and a bitter rival of Tycho Brahe.

Through their letters, Tycho and Kepler discussed a broad range of astronomical problems, dwelling on lunar phenomena and Copernican theory (particularly its theological viability).

To that end, Kepler composed an essay—dedicated to Ferdinand—in which he proposed a force-based theory of lunar motion: "In Terra inest virtus, quae Lunam ciet" ("There is a force in the earth which causes the moon to move").

Though Kepler took a dim view of the attempts of contemporary astrologers to precisely predict the future or divine specific events, he had been casting well-received detailed horoscopes for friends, family, and patrons since his time as a student in Tübingen.

[41] Officially, the only acceptable religious doctrines in Prague were Catholic and Utraquist, but Kepler's position in the imperial court allowed him to practice his Lutheran faith unhindered.

The emperor nominally provided an ample income for his family, but the difficulties of the over-extended imperial treasury meant that actually getting hold of enough money to meet financial obligations was a continual struggle.

[45] Over the following years, Kepler attempted (unsuccessfully) to begin a collaboration with Italian astronomer Giovanni Antonio Magini, and dealt with chronology, especially the dating of events in the life of Jesus.

Following her eventual acquittal, Kepler composed 223 footnotes to the story—several times longer than the actual text—which explained the allegorical aspects as well as the considerable scientific content (particularly regarding lunar geography) hidden within the text.

At the University of Tübingen in Württemberg, concerns over Kepler's perceived Calvinist heresies in violation of the Augsburg Confession and the Formula of Concord prevented his return.

[54] Kepler's belief that God created the cosmos in an orderly fashion caused him to attempt to determine and comprehend the laws that govern the natural world, most profoundly in astronomy.

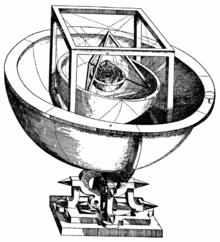

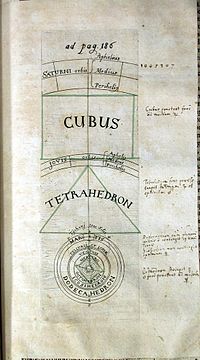

Kepler claimed to have had an epiphany on 19 July 1595, while teaching in Graz, demonstrating the periodic conjunction of Saturn and Jupiter in the zodiac: he realized that regular polygons bound one inscribed and one circumscribed circle at definite ratios, which, he reasoned, might be the geometrical basis of the universe.

After failing to find a unique arrangement of polygons that fit known astronomical observations (even with extra planets added to the system), Kepler began experimenting with 3-dimensional polyhedra.

Much of Kepler's enthusiasm for the Copernican system stemmed from his theological convictions about the connection between the physical and the spiritual; the universe itself was an image of God, with the Sun corresponding to the Father, the stellar sphere to the Son, and the intervening space between them to the Holy Spirit.

Modern astronomy owes much to Mysterium Cosmographicum, despite flaws in its main thesis, "since it represents the first step in cleansing the Copernican system of the remnants of the Ptolemaic theory still clinging to it.

[64] Kepler calculated and recalculated various approximations of Mars's orbit using an equant (the mathematical tool that Copernicus had eliminated with his system), eventually creating a model that generally agreed with Tycho's observations to within two arcminutes (the average measurement error).

[71] Finding that an elliptical orbit fit the Mars data (the Vicarious Hypothesis), Kepler immediately concluded that all planets move in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus—his first law of planetary motion.

[74] Although it explicitly extended the first two laws of planetary motion (applied to Mars in Astronomia nova) to all the planets as well as the Moon and the Medicean satellites of Jupiter,[note 2] it did not explain how elliptical orbits could be derived from observational data.

[77] Originally intended as an introduction for the uninitiated, Kepler sought to model his Epitome after that of his master Michael Maestlin, who published a well-regarded book explaining the basics of geocentric astronomy to non-experts.

In the interim, and to avoid being subject to the ban, Kepler switched the audience of the Epitome from beginners to that of expert astronomers and mathematicians, as the arguments became more and more sophisticated and required advanced mathematics to be understood.

[84] In his bid to become imperial astronomer, Kepler wrote De Fundamentis (1601), whose full title can be translated as “On Giving Astrology Sounder Foundations”, as a short foreword to one of his yearly almanacs.

As a shepherd is pleased by the piping of a flute without understanding the theory of musical harmony, so likewise Earth responds to the angles and aspects made by the heavens but not in a conscious manner.

Nominally this work—presented to the common patron of Roeslin and Feselius—was a neutral mediation between the feuding scholars (the titled meaning "Third-party interventions"), but it also set out Kepler's general views on the value of astrology, including some hypothesized mechanisms of interaction between planets and individual souls.

When conjoined with Christiaan Huygens' newly discovered law of centrifugal force, it enabled Isaac Newton, Edmund Halley, and perhaps Christopher Wren and Robert Hooke to demonstrate independently that the presumed gravitational attraction between the Sun and its planets decreased with the square of the distance between them.

In it, Kepler described the inverse-square law governing the intensity of light, reflection by flat and curved mirrors, and principles of pinhole cameras, as well as the astronomical implications of optics such as parallax and the apparent sizes of heavenly bodies.

[103] Kepler wrote the influential mathematical treatise Nova stereometria doliorum vinariorum in 1613, on measuring the volume of containers such as wine barrels, which was published in 1615.

These and other histories written from an Enlightenment perspective treated Kepler's metaphysical and religious arguments with skepticism and disapproval, but later Romantic-era natural philosophers viewed these elements as central to his success.

Physicist Wolfgang Pauli even used Kepler's priority dispute with Robert Fludd to explore the implications of analytical psychology on scientific investigation.

[131] Hindemith's opera inspired John Rodgers and Willie Ruff of Yale University to create a synthesizer composition based on Kepler's scheme for representing planetary motion with music.