Kerala model

[1][2] Academic literature discusses the primary factors underlying the success of the Kerala model as its decentralization efforts, the political mobilization of the poor, and the active involvement of civil society organizations in the planning and implementation of development policies.

[3] More precisely, the Kerala model has been defined as: The Kerala model originally differed from conventional development thinking which focuses on achieving high GDP growth rates, however, in 1990, Pakistani economist Mahbub ul Haq changed the focus of development economics from national income accounting to people centered policies.

[9] Kerala's improved public health relative to other Indian states and countries with similar economic circumstances is founded on a long history of successful health-focused policies.

Thus, leaders in Kerala began increasing spending on health, education, and public transportation, establishing progressive social policies.

[12][16] The state's high minimum wages, road expansion, strong trade and labor unions, land reforms, and investment in clean water, sanitation, housing, access to food, public health infrastructure, and education all contributed to the relative success of Kerala's public health system.

[12][19] In addition, smaller private medical institutions complemented the government's efforts to increase access to health services and provided specialized healthcare.

Moreover, the campaign emphasized improving care and access, regardless of income level, caste, tribe, or gender, reflecting a goal of not just effective but also equitable coverage.

[27][10] There is an active, state-supported nutrition programme for pregnant and new mothers and about 99% of child births are institutional/hospital deliveries,[28] leading to infant mortality in 2018 being 7 per thousand,[29] compared to 28 in India, overall[30] and 18.9 for low- middle income countries generally.

In early 2000, more than a quarter of the population faced severe undernutrition in three states—Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh—though they had a higher average dietary intake than Kerala.

Kerala's improved nutrition is primarily due to better healthcare access as well as greater equality in food distribution across different income groups and within families.

In pre-colonial Kerala, women, especially those belonging to the matrilineal Nair caste, received an education in Sanskrit and other sciences, as well as Kalaripayattu, a martial art.

[30] Another indicator of gender equality and women's health is the maternal mortality rate, which is 53.59 per 100,000 live births in Kerala and 178.35 in the rest of India.

[35] Historically, women in Kerala are thought to have possessed more autonomy relative to other Indian states, which is often attributed to its matrilineal structure which ultimately changed into a patrilineal system in the 20th century.

[66][67][68][65][69] Matriliny, in which property was inherited collectively through the female line, was largely practiced by the Hindu Nair caste as well as some other upper-caste Hindus such as the Ezhavas and even some Muslims, who are exclusively patriarchal in other parts of India.

For instance, unmarried daughters could only claim between a quarter and a third of each son's share of paternal property, or 5,000 rupees, whichever was less, if the father died without making a will.

These laws were challenged when Mary Roy, a Syrian Christian woman who had not received a dowry sued her brother to gain equal access to their inheritance.

Beginning in the 1920s, the Hindu matriarchal system fragmented, especially once the Travancore Nayar Regulation Act of 1925 was passed, which was initiated by the British and began the transition to a strictly patriarchal structure.

[65] By the 1970s, the matrilineal system had virtually disappeared and the Kerala family organization became exclusively patrilineal and women's rights to property were significantly restricted.

[63][66] Societal and cultural norms are argued by scholars to continue to restrict women's freedoms and maintain their subservience to men both at home and in the labor market.

The land reform initiative abolished tenancy and landlord exploitation, effective public food distribution that provides subsidised rice to low-income households, protective laws for agricultural workers, pensions for retired agricultural laborers, and a high rate of government employment for members of formerly lower-caste communities.

Democratization of the state has surrounded significant increases in components of welfare and has led to a large social transformation since the early 20th century.

Comparisons of scheduled tribes, castes, and religions also show growing income disparities, reflected by increasing incidence of suicides, family violence, gang activity, and alcoholism, among others.

With regard to public expenditure on health and family welfare, there too has been an equally sharp fall in spending, from 11.67% of state domestic product (SDP) to 1983–84 to 9.94% in 1989-90 and down to 6.36% in 2005–06.

Under the current neoliberal regime there has been accelerated commercialization of the education and health sectors—which has altered the equity base of the Kerala model as a whole.

[77] Poverty is also prevalent in marine fishing communities that are often located on the geographical margins of the land who depend exclusive on the sea for their livelihood.

These weaknesses should not be overlooked, but they remain minor compared with Kerala's continuing overall ability to deliver a high material quality of life to its people as the indicators show.

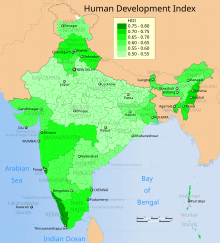

Oommen and Anandaraj district-level profile (1996) found 9 of Kerala's 14 districts among the top 12 in all of India on a composite of literacy, life expectancy, and several economic variables.

[81] The liberalization-cum-structural adjustment package of the Fund and the Bank presents a philosophy that asserts that the working masses need to make sacrifices today for the sake of providing incentives to capitalists for higher growth, from which those same workers would benefit later.

The ‘reforms’ observed, then, are more of a reflection of the structural changes made by the Indian economy which has increased supply side incentives for capitalists.

This has led to a rise in the degree of exploitation of the working people by cutting their so-called social wage and wrecking the internal balance of the production-structure, which should be taken into consideration when looking at the Kerala Model as a worthwhile example for other third world states.