Kerr metric

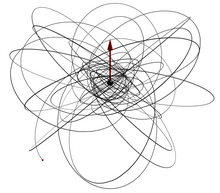

These four related solutions may be summarized by the following table, where Q represents the body's electric charge and J represents its spin angular momentum: According to the Kerr metric, a rotating body should exhibit frame-dragging (also known as Lense–Thirring precession), a distinctive prediction of general relativity.

The light from distant sources can travel around the event horizon several times (if close enough); creating multiple images of the same object.

The LIGO experiment that first detected gravitational waves, announced in 2016, also provided the first direct observation of a pair of Kerr black holes.

This implies that there is coupling between time and motion in the plane of rotation that disappears when the black hole's angular momentum goes to zero.

are related by[23][24] Since even a direct check on the Kerr metric involves cumbersome calculations, the contravariant components

An "ice skater", in orbit over the equator and rotationally at rest with respect to the stars, extends her arms.

A rotating black hole has the same static limit at its event horizon but there is an additional surface outside the event horizon named the "ergosurface" given by in Boyer–Lindquist coordinates, which can be intuitively characterized as the sphere where "the rotational velocity of the surrounding space" is dragged along with the velocity of light.

The region outside the event horizon but inside the surface where the rotational velocity is the speed of light, is called the ergosphere (from Greek ergon meaning work).

The net process is that the rotating black hole emits energetic particles at the cost of its own total energy.

Rotating black holes in astrophysics are a potential source of large amounts of energy and are used to explain energetic phenomena, such as gamma-ray bursts.

The Kerr geometry exhibits many noteworthy features: the maximal analytic extension includes a sequence of asymptotically flat exterior regions, each associated with an ergosphere, stationary limit surfaces, event horizons, Cauchy horizons, closed timelike curves, and a ring-shaped curvature singularity.

Topologically, the homotopy type of the Kerr spacetime can be simply characterized as a line with circles attached at each integer point.

This instability means that although the Kerr metric is axis-symmetric, a black hole created through gravitational collapse may not be so.

[13] This instability also implies that many of the features of the Kerr geometry described above may not be present inside such a black hole.

A beam of light traveling in the same direction as the black hole's spin will circularly orbit at the inner photon sphere.

In physics, symmetries are typically associated with conserved constants of motion, in accordance with Noether's theorem.

[34] The Kerr metric, which describes the spacetime geometry around a rotating black hole, can be extended beyond the inner event horizon.

A negative mass is a highly unusual concept in general relativity, and its physical interpretation is still debated.

The presence of CTCs raises fundamental questions about the predictability and consistency of the laws of physics in these extreme regions of spacetime.

[27][28] While the physical reality of the anti-universe remains uncertain, its study provides valuable insights into the nature of spacetime, gravity, and the limits of our current understanding of the universe While it is expected that the exterior region of the Kerr solution is stable, and that all rotating black holes will eventually approach a Kerr metric, the interior region of the solution appears to be unstable, much like a pencil balanced on its point.

The Kerr geometry is a particular example of a stationary axially symmetric vacuum solution to the Einstein field equation.

The interior of the Kerr geometry, or rather a portion of it, is locally isometric to the Chandrasekhar–Ferrari CPW vacuum, an example of a colliding plane wave model.

This is particularly interesting, because the global structure of this CPW solution is quite different from that of the Kerr geometry, and in principle, an experimenter could hope to study the geometry of (the outer portion of) the Kerr interior by arranging the collision of two suitable gravitational plane waves.

Each asymptotically flat Ernst vacuum can be characterized by giving the infinite sequence of relativistic multipole moments, the first two of which can be interpreted as the mass and angular momentum of the source of the field.

There are alternative formulations of relativistic multipole moments due to Hansen, Thorne, and Geroch, which turn out to agree with each other.

The relativistic multipole moments of the Kerr geometry were computed by Hansen; they turn out to be Thus, the special case of the Schwarzschild vacuum (

[a] Weyl multipole moments arise from treating a certain metric function (formally corresponding to Newtonian gravitational potential) which appears the Weyl–Papapetrou chart for the Ernst family of all stationary axisymmetric vacuum solutions using the standard euclidean scalar multipole moments.

In the case of solutions symmetric across the equatorial plane the odd order Weyl moments vanish.

Perez and Moreschi have given an alternative notion of "monopole solutions" by expanding the standard NP tetrad of the Ernst vacuums in powers of

The Kerr geometry is often used as a model of a rotating black hole but if the solution is held to be valid only outside some compact region (subject to certain restrictions), in principle, it should be able to be used as an exterior solution to model the gravitational field around a rotating massive object other than a black hole such as a neutron star, or the Earth.