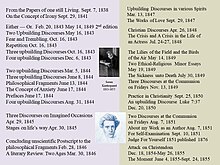

Søren Kierkegaard

Much of his philosophical work deals with the issues of how one lives as a "single individual", giving priority to concrete human reality over abstract thinking and highlighting the importance of personal choice and commitment.

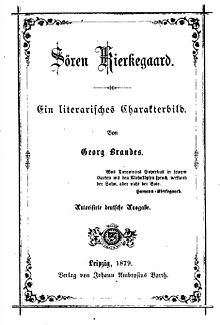

Kierkegaard wrote in Danish and the reception of his work was initially limited to Scandinavia, but by the turn of the 20th century his writings were translated into French, German, and other major European languages.

The figure of Socrates, whom Kierkegaard encountered in Plato's dialogues, would prove to be a phenomenal influence on the philosopher's later interest in irony, as well as his frequent deployment of indirect communication.

Upon submitting it in June 1841, a panel of faculty judged that his work demonstrated considerable intellect while criticizing its informal tone; however, Kierkegaard was granted permission to proceed with its defense.

[62][63] As the title suggests, the thesis dealt with irony and Socrates; the influence of Kierkegaard's friend Poul Martin Møller, who had died in 1838, is evident in the subject matter.

And up there in the higher regions of comparison, smiling vanity plays its false game and deceives the happy ones so that they receive no impression from those lofty, simple thoughts, those first thoughts.Kierkegaard believed God comes to each individual mysteriously.

[105] He put it this way in 1847: "You are indistinguishable from anyone else among those whom you might wish to resemble, those who in the decision are with the good—they are all clothed alike, girdled about the loins with truth, clad in the armor of righteousness, wearing the helmet of salvation!

In Fear and Trembling, I am just as little, precisely just as little, Johannes de Silentio as the knight of faith he depicts, and in turn just as little the author of the preface to the book, which is the individuality—lines of a poetically actual subjective thinker.

[126] On 22 December 1845, Peder Ludvig Møller, who studied at the University of Copenhagen at the same time as Kierkegaard, published an article indirectly criticizing Stages on Life's Way.

A critique of the novel Two Ages (in some translations Two Generations) written by Thomasine Christine Gyllembourg-Ehrensvärd, Kierkegaard made several insightful observations on what he considered the nature of modernity and its passionless attitude towards life.

For this reason we rightfully regard it as a sign of false spirituality to parade a noticeable difference—which is merely sensate, whereas the spirit's manner is the metaphor's quiet, whispering secret—for the person who has ears to hear.

187–188 (From Christian Discourses Translated by Walter Lowrie 1940, 1961)Kierkegaard tried to explain his prolific use of pseudonyms again in The Point of View of My Work as an Author, his autobiographical explanation for his writing style.

In the month of December 1845 the manuscript of the Concluding Postscript was completely finished, and, as my custom was, I had delivered the whole of it at once to Lune [the printer]—which the suspicious do not have to believe on my word, since Luno's account-book is there to prove it.

Suppose, then, that one of them did nothing but moan, while the other forgot and surmounted his own suffering to speak comfortingly, friendly words or, what involved great pain, dragged himself to some water to fetch the other a refreshing drink.

[160][161] Kierkegaard's final years were taken up with a sustained, outright attack on the Church of Denmark by means of newspaper articles published in The Fatherland (Fædrelandet) and a series of self-published pamphlets called The Moment (Øjeblikket), also translated as The Instant.

[188][189] Edwin Björkman credited Kierkegaard, as well as Henry Thomas Buckle and Eduard von Hartmann, with shaping Strindberg's artistic form "until he was strong enough to stand wholly on his own feet.

[194] The final stage is marked in terms of discontinuity and radical change, and thus requires a leap to faith similar to that of Kierkegaard, what Johnson styles an irrefutable claim (uafviselig Fordring) of higher existence correlate to True Being (sande Væsen).

The intensity of his inner life, again—which finds expression in his published works, and even more directly in his notebooks and diaries (also published)—cannot be properly understood without some reference to his father.Friedrich von Hügel wrote about Kierkegaard in his 1913 book, Eternal life: a study of its implications and applications, where he said: "Kierkegaard, the deep, melancholy, strenuous, utterly uncompromising Danish religionist, is a spiritual brother of the great Frenchman, Blaise Pascal, and of the striking English Tractarian, Hurrell Froude, who died young and still full of crudity, yet left an abiding mark upon all who knew him well.

But Kierkegaard, the writer who holds the indispensable key to the intellectual life of Scandinavia, to whom Denmark in particular looks up as her most original man of genius in the nineteenth century, we have wholly overlooked.

[224][225] Swenson stated: "It would be interesting to speculate upon the reputation that Kierkegaard might have attained, and the extent of the influence he might have exerted, if he had written in one of the major European languages, instead of in the tongue of one of the smallest countries in the world.

[234][235] In the 1930s, the first academic English translations,[236] by Alexander Dru, David F. Swenson, Douglas V. Steere, and Walter Lowrie appeared, under the editorial efforts of Oxford University Press editor Charles Williams,[237] one of the members of the Inklings.

Besides affecting Barth deeply, the philosophy of Kierkegaard has found voice in the works of Ibsen, Unamuno, and Heidegger, and its sphere of influence seems to be growing in ever widening circles.

The article goes on to say, But the orthodox, textbook precursor of modern existentialism was the Danish theologian Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855), a lonely, hunchbacked writer who denounced the established church and rejected much of the then-popular German idealism—in which thought and ideas, rather than things perceived through the senses, were held to constitute reality.

[252][253] Important for the first phase of his reception in Germany was the establishment of the journal Zwischen den Zeiten (Between the Ages) in 1922 by a heterogeneous circle of Protestant theologians: Karl Barth, Emil Brunner, Rudolf Bultmann and Friedrich Gogarten.

[254] At roughly the same time, Kierkegaard was discovered by several proponents of the Jewish-Christian philosophy of dialogue in Germany, namely by Martin Buber, Ferdinand Ebner, and Franz Rosenzweig.

[262] Kierkegaard has been called a philosopher, a theologian,[263] the Father of Existentialism,[264][265][266] both atheistic and theistic variations,[267] a literary critic,[137][page needed] a social theorist,[268] a humorist,[269] a psychologist,[9] and a poet.

[276] This is how Kierkegaard put it: "What a priceless invention statistics are, what a glorious fruit of culture, what a characteristic counterpart to the de te narratur fabula [the tale is told about you] of antiquity.

[306][c] Kierkegaard's political philosophy has been likened to neoconservatism, despite its major influence on radical and anti-traditional thinkers, religious and secular, such as Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Jean Paul Sartre.

His fame as a philosopher grew tremendously in the 1930s, in large part because the ascendant existentialist movement pointed to him as a precursor, although later writers celebrated him as a highly significant and influential thinker in his own right.

Figures deeply influenced by his work include W. H. Auden, Jorge Luis Borges, Don DeLillo, Hermann Hesse, Franz Kafka,[321] David Lodge, Flannery O'Connor, Walker Percy, Rainer Maria Rilke, J.D.