King James Version

Noted for its "majesty of style", the King James Version has been described as one of the most important books in English culture and a driving force in the shaping of the English-speaking world.

[5] In Switzerland the first generation of Protestant Reformers had produced the Geneva Bible[6] which was published in 1560[7] having referred to the original Hebrew and Greek scriptures, which was influential in the writing of the Authorized King James Version.

James convened the Hampton Court Conference in January 1604, where a new English version was conceived in response to the problems of the earlier translations perceived by the Puritans,[8] a faction of the Church of England.

[9] James gave translators instructions intended to ensure the new version would conform to the ecclesiology, and reflect the episcopal structure, of the Church of England and its belief in an ordained clergy.

[5] When Mary I succeeded to the throne in 1553, she returned the Church of England to the communion of the Catholic faith and many English religious reformers fled the country,[37] some establishing an English-speaking community in the Protestant city of Geneva.

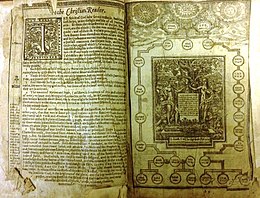

As the work proceeded, more detailed rules were adopted as to how variant and uncertain readings in the Hebrew and Greek source texts should be indicated, including the requirement that words supplied in English to 'complete the meaning' of the originals should be printed in a different type face.

[erbury] signifying unto them, that we do well and straitly charge everyone of them ... that (all excuses set apart) when a prebend or parsonage ... shall next upon any occasion happen to be void ... we may commend for the same some such of the learned men, as we shall think fit to be preferred unto it ...

[f] Robert Barker invested very large sums in printing the new edition, and consequently ran into serious debt,[65] such that he was compelled to sub-lease the privilege to two rival London printers, Bonham Norton and John Bill.

[67] There followed decades of continual litigation, and consequent imprisonment for debt for members of the Barker and Norton printing dynasties,[67] while each issued rival editions of the whole Bible.

[citation needed] In the Great Bible, readings derived from the Vulgate but not found in published Hebrew and Greek texts had been distinguished by being printed in smaller roman type.

[77] In the Geneva Bible, a distinct typeface had instead been applied to distinguish text supplied by translators, or thought needful for English grammar but not present in the Greek or Hebrew; and the original printing of the Authorized Version used roman type for this purpose, albeit sparsely and inconsistently.

When, from the later 17th century onwards, the Authorized Version began to be printed in roman type, the typeface for supplied words was changed to italics, this application being regularized and greatly expanded.

During the Commonwealth a commission was established by Parliament to recommend a revision of the Authorized Version with acceptably Protestant explanatory notes,[85] but the project was abandoned when it became clear that these would nearly double the bulk of the Bible text.

[citation needed] Furthermore, disputes over the lucrative rights to print the Authorized Version dragged on through the 17th century, so none of the printers involved saw any commercial advantage in marketing a rival translation.

Hugh Broughton, who was the most highly regarded English Hebraist of his time but had been excluded from the panel of translators because of his utterly uncongenial temperament,[89] issued in 1611 a total condemnation of the new version.

For most of the 17th century the assumption remained that, while it had been of vital importance to provide the scriptures in the vernacular for ordinary people, nevertheless for those with sufficient education to do so, Biblical study was best undertaken within the international common medium of Latin.

In addition, Blayney and Parris thoroughly revised and greatly extended the italicization of "supplied" words not found in the original languages by cross-checking against the presumed source texts.

For a period, Cambridge continued to issue Bibles using the Parris text, but the market demand for absolute standardization was now such that they eventually adapted Blayney's work but omitted some of the idiosyncratic Oxford spellings.

[h] Another important exception was the 1873 Cambridge Paragraph Bible, thoroughly revised, modernized and re-edited by F. H. A. Scrivener, who for the first time consistently identified the source texts underlying the 1611 translation and its marginal notes.

[129] Cambridge University Press introduced a change at 1 John 5:8[130] in 1985, reversing its longstanding tradition of printing the word "spirit" in lower case by using a capital letter "S".

Hardin of Bedford, Pennsylvania, wrote a letter to Cambridge inquiring about this verse, and received a reply on 3 June 1985 from the Bible Director, Jerry L. Hooper, claiming that it was a "matter of some embarrassment regarding the lower case 's' in Spirit".

For the Old Testament, the translators used a text originating in the editions of the Hebrew Rabbinic Bible by Daniel Bomberg (1524/5),[143][failed verification] but adjusted this to conform to the Greek LXX or Latin Vulgate in passages to which Christian tradition had attached a Christological interpretation.

In the early seventeenth century, the source Greek texts of the New Testament which were used to produce Protestant Bible versions were mainly dependent on manuscripts of the late Byzantine text-type, and they also contained minor variations which became known as the Textus Receptus.

[3][needs context] In a period of rapid linguistic change the translators avoided contemporary idioms, tending instead towards forms that were already slightly archaic, like verily and it came to pass.

[l] Another sign of linguistic conservatism is the invariable use of -eth for the third person singular present form of the verb, as at Matthew 2:13: "the Angel of the Lord appeareth to Joseph in a dreame".

[171] Hence, where the Geneva Bible might use a common English word, and gloss its particular application in a marginal note, the Authorized Version tends rather to prefer a technical term, frequently in Anglicized Latin.

While the Authorized Version remains among the most widely sold, modern critical New Testament translations differ substantially from it in a number of passages, primarily because they rely on source manuscripts not then accessible to (or not then highly regarded by) early-17th-century Biblical scholarship.

The protection that the Authorized Version, and also the Book of Common Prayer, enjoy is the last remnant of the time when the Crown held a monopoly over all printing and publishing in the United Kingdom.

[200] The standardization of the text of the Authorized Version after 1769 together with the technological development of stereotype printing made it possible to produce Bibles in large print-runs at very low unit prices.

For commercial and charitable publishers, editions of the Authorized Version without the apocrypha reduced the cost, while having increased market appeal to non-Anglican Protestant readers.