History of Cornwall

Cornwall, along with the neighbouring county of Devon, maintained Stannary institutions that granted some local control over its most important product, tin, but by the time of Henry VIII most vestiges of Cornish autonomy had been removed as England became an increasingly centralised state under the Tudor dynasty.

By the end of the 18th century, Cornwall was administered as an integral part of the Kingdom of Great Britain along with the rest of England and the Cornish language had gone into steep decline.

The Industrial Revolution brought huge change to Cornwall, as well as the adoption of Methodism among the general populace, turning the area nonconformist.

[2][3] Cornwall and neighbouring Devon had large reserves of tin, which was mined extensively during the Bronze Age by people associated with the Beaker culture.

Ingots of tin, some recovered from shipwrecks dated to the 12th century BCE off the coast of modern Israel, were analysed isotopically and found to have originated in Cornwall.

[4] There is evidence of a relatively large-scale disruption of cultural practices around the 12th century BCE that some scholars think may indicate an invasion or migration into southern Britain.

Here then the merchants buy the tin from the natives and carry it over to Gaul, and after travelling overland for about thirty days, they finally bring their loads on horses to the mouth of the Rhône.

The ancient Greeks and Romans used the name Belerion or Bolerium for the south-west tip of the island of Britain, but the late-Roman source for the Ravenna Cosmography (compiled about 700 CE) introduces a place-name Puro coronavis, the first part of which seems to be a misspelling of Duro (meaning Fort).

This appears to indicate that the tribe of the Cornovii, known from earlier Roman sources as inhabitants of an area centred on modern Shropshire, had by about the 5th century established a power-base in the south-west (perhaps at Tintagel).

John Morris suggested that a contingent of the Shropshire Cornovii was sent to South West Britain at the end of the Roman era, to rule the land there and keep out the invading Irish, but this theory was dismissed by Professor Philip Payton in his book Cornwall: A History.

Experts say the discovery challenges the belief that Romans did not settle in the county and stopped in east Devon where Isca Dumnoniorum became a flourishing provincial capital of the Dumnonii.

Fleuriot suggests that an overland route connecting Padstow with Fowey and Lostwithiel served, in Roman times, as a convenient conduit for trade between Gaul (especially Armorica) and the western parts of the British Isles.

[22] Archaeological sites at Chysauster Ancient Village and Carn Euny in West Penwith and the Isles of Scilly demonstrate a uniquely Cornish 'courtyard house' architecture built in stone of the Roman period, entirely distinct from that of southern Britain, yet with parallels in Atlantic Ireland, North Britain and the Continent, and influential on the later development of stone-built fortified homesteads known in Cornwall as "Rounds".

[28] However, according to John Reuben Davies, Dumnonia ceased to exist around the beginning of the ninth century, but: In 814, King Egbert of Wessex ravaged Cornwall "from the east to the west", and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that in 825 the Cornish fought the men of Devon.

[34] William of Malmesbury, writing around 1120, says that in about 927, King Æthelstan of England expelled the Cornish from Exeter and fixed Cornwall's eastern boundary at the River Tamar.

[35] John Reuben Davies sees the expedition as the suppression of a British uprising, which was followed by the confinement of the Cornish beyond the Tamar and the creation of a separate bishopric for Cornwall.

Cornish saints such as Piran, Meriasek, or Geraint exercised a religious and arguably political influence; they were often closely connected to the local civil rulers and in some cases were kings themselves.

[citation needed] The early organisation and affiliations of the Church in Cornwall are unclear, but in the mid-9th century it was led by a Bishop Kenstec with his see at Dinurrin, a location which has sometimes been identified as Bodmin and sometimes as Gerrans.

[41] The chronology of English expansion into Cornwall is unclear, but it had been absorbed into England by the reign of Edward the Confessor (1042–1066), when it apparently formed part of Godwin's and later Harold's earldom of Wessex.

[44] Mills argues that the Breton rulers of Cornwall, as allies of the Normans, brought about an 'Armorican Return'[44] with Cornu-Breton retaining its status as a prestige language.

[46] and further proposed this period for the early composition of the Tristan and Iseult cycle by poets such as Béroul from a pre-existing shared Brittonic oral tradition.

Some land was held by King William and by existing monasteries – the remainder by the Bishop of Exeter, and a single manor each by Judhael of Totnes and Gotshelm[49] (brother of Walter de Claville).

They therefore wished church services to continue to be conducted in Latin; although they did not understand this language either, it had the benefit of long-established tradition and lacked the political and cultural connotations of the use of English.

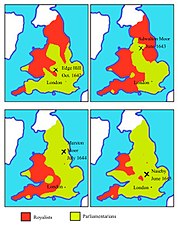

Grenville tried to use "Cornish particularist sentiment" to muster support for the Royalist cause and put a plan to the Prince which would, if implemented, have created a semi-independent Cornwall.

As Cornwall's reserves of tin began to be exhausted, many Cornishmen emigrated to places such as the Americas, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa where their skills were in demand.

Since the decline of tin mining, agriculture and fishing, the area's economy has become increasingly dependent on tourism—some of Britain's most spectacular coastal scenery can be found here.

[63] Resisting the established church, many ordinary Cornish people were Roman Catholic or non-religious until the late 18th century, when Methodism was introduced to Cornwall during a series of visits by John and Charles Wesley.

In 1841 there were ten hundreds of Cornwall: Stratton, Lesnewth and Trigg; East and West Wivelshire; Powder; Pydar; Kerrier; Penwith; and Scilly.

By the 19th century, a large proportion of the population of Cornwall – an estimated 10,000 people, including women and children – were thought to take part in the smuggling business.

[65] A revival of interest in Cornish studies began in the early 20th century with the work of Henry Jenner and the building of links with the other five Celtic nations.