Kingdom of Scotland

In the early period, the kings of the Scots depended on the great lords—the mormaers and toísechs—but from the reign of David I, sheriffdoms were introduced, which allowed more direct control and gradually limited the power of the major lordships.

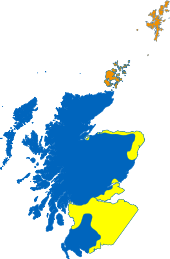

Of these, the four most important were those of the Picts in the north-east, the Scots of Dál Riata in the west, the Britons of Strathclyde in the south-west and the Anglian kingdom of Bernicia (which united with Deira to form Northumbria in 653) in the south-east, stretching into modern northern England.

[9] The long reign (900–942/3) of Donald's successor Causantín (Constantine II) is often regarded as the key to formation of the Kingdom of Alba/Scotland, and he was later credited with bringing Scottish Christianity into conformity with the Catholic Church.

[11] His successor, Indulf the Aggressor, was described as the King of Strathclyde before inheriting the throne of Alba; he is credited with later annexing parts of Lothian, including Edinburgh, from the Kingdom of Northumbria.

The reign of David I has been characterised as a "Davidian Revolution",[12][13] in which he introduced a system of feudal land tenure, established the first royal burghs in Scotland and the first recorded Scottish coinage, and continued a process of religious and legal reforms.

[21] In the 16th century, under James V of Scotland and Mary, Queen of Scots, the Crown and court took on many of the attributes of the Renaissance and New Monarchy, despite long royal minorities, civil wars and interventions by the English and French.

The council supervised the administration of the law, regulated trade and shipping, took emergency measures against the plague, granted licences to travel, administered oaths of allegiance, banished beggars and gypsies, dealt with witches, recusants, Covenanters and Jacobites and tackled the problem of lawlessness in the Highlands and the Borders.

[37] The Privy Council, which developed in the mid-16th century,[38] and the great offices of state, including the chancellor, secretary and treasurer, remained central to the administration of the government, even after the departure of the Stuart monarchs to rule in England from 1603.

[42] In the early modern era, Parliament was also vital to the running of the country, providing laws and taxation, but it had fluctuating fortunes and was never as central to the national life as its counterpart in England.

[43] In the early period, the kings of the Scots depended on the great lords of the mormaers (later earls) and toísechs (later thanes), but from the reign of David I, sheriffdoms were introduced, which allowed more direct control and gradually limited the power of the major lordships.

Knowledge of the nature of Scots law before the 11th century is largely speculative,[47] but it was probably a mixture of legal traditions representing the different cultures inhabiting the land at the time, including Celtic, Britonnic, Irish and Anglo-Saxon customs.

[75]At its borders in 1707, the Kingdom of Scotland was half the size of England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland lochs, it had roughly the same amount of coastline at 4,000 miles (6,400 kilometres).

[78] The Central Lowland belt averages about 50 miles (80 kilometres) in width[79] and, because it contains most of the good quality agricultural land and has easier communications, could support most of the urbanisation and elements of conventional government.

The early modern era also saw the impact of the Little Ice Age, with 1564 seeing thirty-three days of continual frost, where rivers and lochs froze, leading to a series of subsistence crises until the 1690s.

[84] Compared with the situation after the redistribution of population in the later Highland Clearances and the Industrial Revolution, these numbers would have been relatively evenly spread over the kingdom, with roughly half living north of the River Tay.

[107] In the late Middle Ages, the problems of schism in the Catholic Church allowed the Scottish Crown to gain greater influence over senior appointments and two archbishoprics had been established by the end of the 15th century.

[108] While some historians have discerned a decline of monasticism in the late Middle Ages, the mendicant orders of friars grew, particularly in the expanding burghs, to meet the spiritual needs of the population.

At this point the majority of the population was probably still Catholic in persuasion and the Kirk would find it difficult to penetrate the Highlands and Islands, but began a gradual process of conversion and consolidation that, compared with reformations elsewhere, was conducted with relatively little persecution.

In December of the same year, matters were taken even further, when at a meeting of the General Assembly in Glasgow the Scottish bishops were formally expelled from the Church, which was then established on a full Presbyterian basis.

[125] Among these the most important intellectual figure was John Duns Scotus, who studied at Oxford, Cambridge and Paris and probably died at Cologne in 1308, becoming a major influence on late medieval religious thought.

[125] These international contacts helped integrate Scotland into a wider European scholarly world and would be one of the most important ways in which the new ideas of humanism were brought into Scottish intellectual life.

[134] Under the Commonwealth, the universities saw an improvement in their funding, as they were given income from deaneries, defunct bishoprics and the excise, allowing the completion of buildings including the college in the High Street in Glasgow.

[138] The universities recovered from the upheavals of the mid-century with a lecture-based curriculum that was able to embrace economics and science, offering a high quality liberal education to the sons of the nobility and gentry.

[139] Defeat on land at the Battle of Largs and winter storms forced the Norwegian fleet to return home, leaving the Scottish Crown as the major power in the region and leading to the ceding of the Western Isles to Alexander in 1266.

[158] Scottish seamen received protection against arbitrary impressment by English men of war, but a fixed quota of conscripts for the Royal Navy was levied from the sea-coast burghs during the second half of the 17th century.

[164] By the High Middle Ages, the kings of Scotland could command forces of tens of thousands of men for short periods as part of the "common army", mainly of poorly armoured spear and bowmen.

In the Late Middle Ages, under the Stewart kings forces were further augmented by specialist troops, particularly men-at-arms and archers, hired by bonds of manrent, similar to English indentures of the same period.

[173] As armed conflict with Charles I in the Bishop's Wars became likely, hundreds of Scots mercenaries returned home from foreign service, including experienced leaders like Alexander and David Leslie and these veterans played an important role in training recruits.

[178] At the Restoration the Privy Council established a force of several infantry regiments and a few troops of horse and there were attempts to found a national militia on the English model.

[188] In the case of Scotland, use of a blue background for the Saint Andrew's Cross is said to date from at least the 15th century,[189] with the first certain illustration of a flag depicting such appearing in Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount's Register of Scottish Arms, c.