Kirātārjunīya

[1] Believed to have been composed in the 6th century or earlier, it consists of eighteen cantos describing the combat between Shiva (in the guise of a kirata, or "mountain-dwelling hunter"), and Arjuna.

[7] Bharavi's work begins with the word śrī (fortune), and the last verse of every canto contains the synonym Lakshmi.

Bhima supports Draupadi, pointing out that it would be shameful to receive their kingdom back as a gift instead of winning it in war, but Yudhiṣṭhira refuses, with a longer speech.

Vyasa points out that the enemy is stronger, and they must use their time taking actions that would help them win a war, if one were to occur at the end of their exile.

He instructs Arjuna to practise ascetism (tapasya) and propitiate Indra to acquire divine weapons for the eventual war.

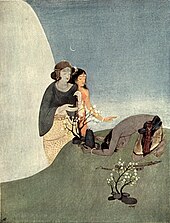

Meanwhile, a celestial army of nymphs (apsaras) sets out from heaven, in order to eventually distract Arjuna.

The nymphs attempt to distract Arjuna, accompanied by musicians and making the best features of all six seasons appear simultaneously.

Finally, Indra arrives as a sage, praises Arjuna's asceticism, but criticises him for seeking victory and wealth instead of liberation — the goddess of Fortune is fickle and indiscriminate.

Arjuna stands his ground, explaining his situation and pointing out that conciliation with evil people would lead one into doing wrong actions oneself.

He gives a further long speech that forms the heart of the epic, on right conduct, self-respect, resoluteness, dignity, and wisdom.

The most popular verse is the 37th from the eighth canto, which describes nymphs bathing in a river, and is noted for its beauty.

[12] A. K. Warder considers it the "most perfect epic available to us", over Aśvaghoṣa's Buddhacarita, noting its greater force of expression, with more concentration and polish in every detail.

Despite using extremely difficult language and rejoicing in the finer points of Sanskrit grammar, Bharavi achieves conciseness and directness.

At times, the narrative is secondary to the interlaced descriptions, elaborate metaphors and similes, and display of mastery in the Sanskrit language.

The seekers (mārgaṇāḥ) of Śiva (jagatīśa) [i.e. the deities and sages], reached (īyuḥ) the sky (vikāśam) [to watch the battle].

"[18] The earliest commentary of Kiratarjuniya was likely on Canto 15, by Western ganga king Durvinita in Kannada, however, this work isn't extant.

[19][20] Bharavi's "power of description and dignity of style" were an inspiration for Māgha's Shishupala Vadha, which is modelled after the Kirātārjunīya and seeks to surpass it.

[10] A vyayoga (a kind of play), also named Kirātārjunīya and based on Bharavi's work, was produced by the Sanskrit dramatist Vatsaraja in the 12th or 13th century.

His commentary on the Kirātārjunīya is known as the Ghaṇṭāpatha (the Bell-Road) and explains the multiple layers of compounds and figures of speech present in the verses.