Shishupala Vadha

In the original story, Shishupala, king of the Chedis in central India, after insulting Krishna several times in an assembly, finally enrages him and has his head struck off.

The 10th-century literary critic Kuntaka observes that Magha arranges the story such that the sole purpose of Vishnu's avatarhood as Krishna is the slaying of the evil Shishupala.

When the story begins, Sage Narada reminds Krishna that while he had previously (in the form of Narasimha) killed Hiranyakashipu, the demon has been reborn as Shishupala and desires to conquer the world, and must be destroyed again.

[2] Meanwhile, Yudhiṣṭhira and his brothers, having conquered the four directions and killed Jarasandha, wish to perform the rajasuya yajña (ceremony) and Krishna has been invited.

While Balarama suggests attacking declaring war on Shishupala immediately, Uddhava points out that this would involve many kings and disrupt Yudhishthira's ceremony (where their presence is required).

The ceremony takes place, and at the end, at Bhishma's advice, the highest honour (arghya) is bestowed on Krishna (Canto XIV).

Finally, Krishna enters the fight (Canto XX), and after a long battle, strikes off Shishupala's head with Sudarshana Chakra, his discus.

Like the Kirātārjunīya, the poem displays rhetorical and metrical skill more than the growth of the plot[4] and is noted for its intricate wordplay, textual complexity and verbal ingenuity.

[7] Because of these descriptions, the Śiśupālavadha is an important source on the history of Indian ornaments and costumes, including its different terms for dress as paridhāna, aṃśuka, vasana, vastra and ambara; upper garments as uttarīya; female lower garments as nīvī, vasana, aṃśuka, kauśeya, adhivāsa and nitambaravastra; and kabandha, a waist-band.

[8] Magha is also noted for technique of developing the theme, "stirring intense and conflicting emotions relieved by lighter situations".

[2] His work is also considered to be difficult, and reading it and Meghadūta can easily consume one's lifetime, according to the saying (sometimes attributed to Mallinātha) māghe meghe gataṃ vayaḥ.

("In reading Māgha and Megha my life was spent", or also the unrelated meaning "In the month of Magha, a bird flew among the clouds".)

The second canto contains a famous verse with a string of adjectives that can be interpreted differently depending on whether they are referring to politics (rāja-nīti, king's policy) or grammar.

[16] The entire 16th canto, a message from Shishupala to Krishna, is intentionally ambiguous, and can be interpreted in two ways: one favourable and pleasing (a humble apology in courteous words), the other offensive and harsh (a declaration of war).

kṛta-gopa-vadhū-rater ghnato vṛṣam ugre narake 'pi saṃprati pratipattir adhaḥkṛtainaso janatābhis tava sādhu varṇyate

"Sri Krishna, the giver of every boon, the scourge of the evil-minded, the purifier, the one whose arms can annihilate the wicked who cause suffering to others, shot his pain-causing arrow at the enemy.

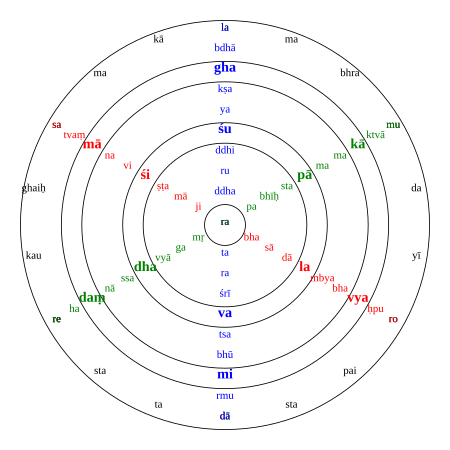

This is known as pratiloma (or gatapratyāgata) and is not found in Bharavi:[19] तं श्रिया घनयानस्तरुचा सारतया तया । यातया तरसा चारुस्तनयानघया श्रितं ॥ taṃ śriyā ghanayānastarucā sāratayā tayā yātayā tarasā cārustanayānaghayā śritaṃ

"[That army], which relished battle (rasāhavā) contained allies who brought low the bodes and gaits of their various striving enemies (sakāranānārakāsakāyasādadasāyakā), and in it the cries of the best of mounts contended with musical instruments (vāhasāranādavādadavādanā).

This is known as samudga:[19] सदैव संपन्नवपू रणेषु स दैवसंपन्नवपूरणेषु । महो दधे 'स्तारि महानितान्तं महोदधेस्तारिमहा नितान्तम् ॥ sadaiva saṃpannavapū raṇeṣu sa daivasaṃpannavapūraṇeṣu maho dadhe 'stāri mahānitāntaṃ mahodadhestārimahā nitāntam