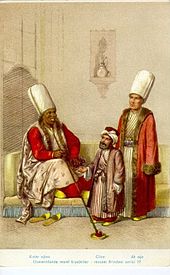

Kizlar agha

The 16th century, however, saw a rapid rise of the population of the Topkapi Palace, including among eunuchs, whose numbers rose from 40 under Selim I (r. 1512–1520) to over a thousand under Murad III.

The kizlar agha was also the de facto sole intermediary between the closed world of the harem and the outer, male quarters of the palace (the selamlik), controlling its provisioning as well as the messages to and from.

[6][8] In addition, he was the only individual allowed to carry the grand vizier's communications to the sultan and had a recognized role in public ceremonies.

[10] Jane Hathaway, a researcher specializing in Ottoman history, also posits that these displaced elite slaves were preferred over free subjects due to concerns about free subject's loyalty - the East African slave's dependence on their new rulers and lack of familial ties would ensure that no regional bias was present.

[13] In Ottoman legal theory, the sultan was supposed to conduct affairs of state exclusively via the grand vizier, but in reality this arrangement was often circumvented.

[14] Thus the kizlar agha's political power, although exercised behind the scenes, was very considerable, influencing imperial policy and at times controlling the appointments to the grand vizierate,[8] or even intervening in dynastic disputes and the succession to the throne.

Beshir Agha was a notable patron of the "Tulip Era" culture then flourishing in the empire, being was engaged in "intellectual and religious pursuits" that according to historian Jateen Lad "contributed to the Ottoman brand of Hanafi Islam and Sunni orthodoxy in general".

[16][17] The kizlar agha also held a special role as the nazir "administrator" of the waqfs designated for the upkeep of the two holy cities (al-Haramayn) of Islam, Mecca and Medina, being responsible for their supply as well as for the annual ritual sending of gifts (sürre) to them.

[1][8][20] Vakifs designated for the upkeep of the Muslim holy places had been established by members of the Ottoman court since early times, and their administration entrusted to special departments already since the late 15th century.

A special treasury, the haremeyn dolabi, contained the revenue from the vakifs, and the kizlar agha held a weekly divan or council to examine the accounts.

[7] In the Topkapi Palace, the kizlar agha had his own spacious apartment near the Aviary Gate, while the other eunuchs under his supervision lived together in cramped and rather squalid conditions in a three-storey barracks.

[9][25] When they were dismissed, the chief black eunuchs received a pension (asatlık, literally "document of liberty") and from 1644 on were exiled to Egypt or the Hejaz.

[16] As a result, serving kizlar aghas often took care to prepare for a comfortable retirement in Egypt by buying property and establishing vakifs of their own there.