Klaus Roth

Klaus Friedrich Roth FRS (29 October 1925 – 10 November 2015) was a German-born British mathematician who won the Fields Medal for proving Roth's theorem on the Diophantine approximation of algebraic numbers.

His parents settled with him in London to escape Nazi persecution in 1933, and he was raised and educated in the UK.

[1][2] His father, a solicitor, had been exposed to poison gas during World War I and died while Roth was still young.

He tried to join the Air Training Corps, but was blocked for some years for being German and then after that for lacking the coordination needed for a pilot.

His Cambridge tutor, John Charles Burkill, was not supportive of Roth continuing in mathematics, recommending instead that he take "some commercial job with a statistical bias".

[2] Instead, he briefly became a schoolteacher at Gordonstoun, between finishing at Cambridge and beginning his graduate studies.

[1][2] On the recommendation of Harold Davenport, he was accepted in 1946 to a master's program in mathematics at University College London, where he worked under the supervision of Theodor Estermann.

[5] His most significant contributions, on Diophantine approximation, progression-free sequences, and discrepancy, were all published in the mid-1950s, and by 1958 he was given the Fields Medal, mathematicians' highest honour.

[2] He took sabbaticals at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the mid-1950s and mid-1960s, and seriously considered migrating to the United States.

Walter Hayman and Patrick Linstead countered this possibility, which they saw as a threat to British mathematics, with an offer of a chair in pure mathematics at Imperial College London, and Roth accepted the chair in 1966.

[1][2][3] They had no children, and Roth dedicated the bulk of his estate, over one million pounds, to two health charities "to help elderly and infirm people living in the city of Inverness".

Harold Davenport writes that the "moral in Dr Roth's work" is that "the great unsolved problems of mathematics may still yield to direct attack, however difficult and forbidding they appear to be, and however much effort has already been spent on them".

More precisely, he proved that for irrational algebraic numbers, the approximation exponent is always exactly two.

These sequences had been studied in 1936 by Paul Erdős and Pál Turán, who conjectured that they must be sparse.

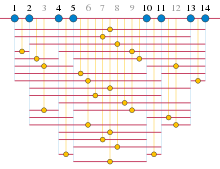

[11][a] However, in 1942, Raphaël Salem and Donald C. Spencer constructed progression-free subsets of the numbers from

[12] Roth vindicated Erdős and Turán by proving that it is not possible for the size of such a set to be proportional to

[14] A strengthening in a different direction, Szemerédi's theorem, shows that dense sets of integers contain arbitrarily long arithmetic progressions.

[15] Although Roth's work on Diophantine approximation led to the highest recognition for him, it is his research on irregularities of distribution that (according to an obituary by William Chen and Bob Vaughan) he was most proud of.

[2] Roth measured this approximation by the squared difference between the number of points and

times the area, and proved that for a randomly chosen rectangle the expected value of the squared difference is logarithmic in

This result is best possible, and significantly improved a previous bound on the same problem by Tatyana Pavlovna Ehrenfest.

[16] Despite the prior work of Ehrenfest and Johannes van der Corput on the same problem, Roth was known for boasting that this result "started a subject".

[2] Some of Roth's earliest works included a 1949 paper on sums of powers, showing that almost all positive integers could be represented as a sum of a square, a cube, and a fourth power, and a 1951 paper on the gaps between squarefree numbers, describes as "quite sensational" and "of considerable importance" respectively by Chen and Vaughan.

[2] His inaugural lecture at Imperial College concerned the large sieve: bounding the size of sets of integers from which many congruence classes of numbers modulo prime numbers have been forbidden.

His 1951 paper on the problem was the first to prove a nontrivial upper bound on the area that can be achieved.

After Paul Erdős and Ronald Graham proved that a more clever tilted packing could leave a significantly smaller area, only

,[19] Roth and Bob Vaughan responded with a 1978 paper proving the first nontrivial lower bound on the problem.

[22] Roth won the Fields Medal in 1958 for his work on Diophantine approximation.

[1] It was a source of amusement to him that his Fields Medal, election to the Royal Society, and professorial chair came to him in the reverse order of their prestige.

[2] The London Mathematical Society gave Roth the De Morgan Medal in 1983.