Know Nothing

[3] Supporters of the Know Nothing movement believed that an alleged "Romanist" conspiracy to subvert civil and religious liberty in the United States was being hatched by Catholics.

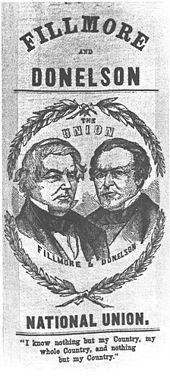

The American Party nominated former President Millard Fillmore in the 1856 presidential election, but he kept quiet about his membership in it, and he personally refrained from supporting the Know Nothing movement's activities and ideology.

In 1857 the Dred Scott v. Sandford pro-slavery decision of the Supreme Court of the United States further galvanized opposition to slavery in the North, causing many former Know Nothings to join the Republicans.

Anti-Catholicism was widespread in colonial America, but it played a minor role in American politics until the arrival of large numbers of Irish and German Catholics started in the 1840s.

They emerged in New York in the early 1850s as a secret order that quickly spread across the North, reaching non-Catholics, particularly those who were lower middle class or skilled workers.

One Boston minister described Catholicism as "the ally of tyranny, the opponent of material prosperity, the foe of thrift, the enemy of the railroad, the caucus, and the school".

[17][18] These fears encouraged conspiracy theories regarding papal intentions of subjugating the United States through a continuing influx of Catholics controlled by Irish bishops obedient to and personally selected by the Pope.

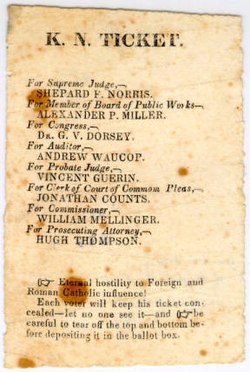

Activists formed secret groups, coordinating their votes and throwing their weight behind candidates who were sympathetic to their cause: Immigration during the first five years of the 1850s reached a level five times greater than a decade earlier.

The Whig candidate for mayor of Philadelphia, editor Robert T. Conrad, was soon revealed as a Know Nothing as he promised to crack down on crime, close saloons on Sundays and only appoint native-born Americans to office—he won the election by a landslide.

Abraham Lincoln was strongly opposed to the principles of the Know Nothing movement, but did not denounce it publicly because he needed the votes of its membership to form a successful anti-slavery coalition in Illinois.

Although most of the new immigrants lived in the North, resentment and anger against them was national and the American Party initially polled well in the South, attracting the votes of many former southern Whigs.

The new party's voters were concentrated in the rapidly growing industrial towns, where Yankee workers faced direct competition with new Irish immigrants.

The legislature set up the state's first reform school for juvenile delinquents while trying to block the importation of supposedly subversive government documents and academic books from Europe.

After this, state courts lost the power to process applications for citizenship and public schools had to require compulsory daily reading of the Protestant Bible (which the nativists were sure would transform the Catholic children).

However, Know Nothing lawmakers failed to reach the two-thirds majority needed to pass a state constitutional amendment to restrict voting and office holding to men who had resided in Massachusetts for at least 21 years.

[45] The most dramatic move by the Know Nothing legislature was to appoint an investigating committee designed to prove widespread sexual immorality underway in Catholic convents.

Whigs supported the American Party because of their desire to defeat the Democrats, their unionist sentiment, their anti-immigrant attitudes and the Know Nothing neutrality on the slavery issue.

Every migrant, no matter how settled or prosperous, also worried that this virulent strain of nativism threatened his or her hard-earned gains in the South and integration into its society.

Immigrants fears were unjustified, however, because the national debate over slavery and its expansion, not nativism or anti-Catholicism, was the major reason for Know-Nothing success in the South.

On August 18, 1853, the party held its first rally in Baltimore with about 5,000 in attendance, calling for secularization of public schools, complete separation of church and state, freedom of speech, and regulating immigration.

[61] Historian Michael F. Holt argues that "Know Nothingism originally grew in the South for the same reasons it spread in the North—nativism, anti-Catholicism, and animosity toward unresponsive politicos—not because of conservative Unionism".

Holt cites William B. Campbell, former governor of Tennessee, who wrote in January 1855: "I have been astonished at the widespread feeling in favor of their principles—to wit, Native Americanism and anti-Catholicism—it takes everywhere".

"[66] Similarly, the broader Know Nothing movement viewed Louisiana Catholics, and in particular the Creole elite who supported the American Party, as adhering to a Gallican Catholicism and therefore opposed to papal authority over matters of state.

While Abraham Lincoln never publicly attacked the Know Nothings, whose votes he needed, he expressed his own disgust with the political party in a private letter to Joshua Speed, written August 24, 1855: I am not a Know-Nothing– That is certain– How could I be?

[74] In the late 19th century, Democrats called the Republicans "Know Nothings" in order to secure the votes of Germans in the Bennett Law campaign in Wisconsin in 1890.

[77] Some historians and journalists "have found parallels with the Birther and Tea Party movements, seeing the prejudices against Latino immigrants and hostility towards Islam as a similarity".

Almost entirely white, and disproportionately male and older, Tea Party advocates express a visceral anger at the cultural and, to some extent, political eclipse of an America in which people who looked and thought like them were dominant (an echo, in its own way, of the anguish of the Know-Nothings).

Though the anti-immigration and Tea Party movements so far have remained largely distinct (even with growing ties), they share an emotional grammar: the fear of displacement.

[74] In 2006, an editorial in The Weekly Standard by neoconservative William Kristol accused populist Republicans of "turning the GOP into an anti-immigration, Know-Nothing party".

[81] In the 2016 United States presidential election, a number of commentators and politicians compared candidate Donald Trump to the Know Nothings due to his anti-immigration policies.