Kondo effect

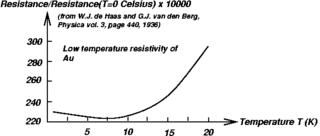

In physics, the Kondo effect describes the scattering of conduction electrons in a metal due to magnetic impurities, resulting in a characteristic change i.e. a minimum in electrical resistivity with temperature.

[1] The cause of the effect was first explained by Jun Kondo, who applied third-order perturbation theory to the problem to account for scattering of s-orbital conduction electrons off d-orbital electrons localized at impurities (Kondo model).

Kondo's calculation predicted that the scattering rate and the resulting part of the resistivity should increase logarithmically as the temperature approaches 0 K.[2] Extended to a lattice of magnetic impurities, the Kondo effect likely explains the formation of heavy fermions and Kondo insulators in intermetallic compounds, especially those involving rare earth elements such as cerium, praseodymium, and ytterbium, and actinide elements such as uranium.

[5] Kondo described the three puzzling aspects that frustrated previous researchers who tried to explain the effect:[6][7] Experiments in the 1960s by Myriam Sarachik at Bell Laboratories showed that phenomenon was caused by magnetic impurity in nominally pure metals.

The Anderson impurity model and accompanying Wilsonian renormalization theory were an important contribution to understanding the underlying physics of the problem.

In the Kondo problem, the coupling refers to the interaction between the localized magnetic impurities and the itinerant electrons.

Extended to a lattice of magnetic ions, the Kondo effect likely explains the formation of heavy fermions and Kondo insulators in intermetallic compounds, especially those involving rare earth elements such as cerium, praseodymium, and ytterbium, and actinide elements such as uranium.

It is believed that a manifestation of the Kondo effect is necessary for understanding the unusual metallic delta-phase of plutonium.

Band-structure hybridization and flat band topology in Kondo insulators have been imaged in angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy experiments.

[18] In 2017, teams from the Vienna University of Technology and Rice University conducted experiments into the development of new materials made from the metals cerium, bismuth and palladium in specific combinations and theoretical work experimenting with models of such structures, respectively.

The results of the experiments were published in December 2017[19] and, together with the theoretical work,[20] lead to the discovery of a new state,[21] a correlation-driven Weyl semimetal.