Comanche

[6] In the 18th and 19th centuries, Comanche lived in most of present-day northwestern Texas and adjacent areas in eastern New Mexico, southeastern Colorado, southwestern Kansas, and western Oklahoma.

Their tribal jurisdictional area is located in Caddo, Comanche, Cotton, Greer, Jackson, Kiowa, Tillman and Harmon counties.

[22] The Proto-Comanche movement to the Plains was part of the larger phenomenon known as the "Shoshonean Expansion" in which that language family spread across the Great Basin and across the mountains into Wyoming.

By the end of the 18th century the struggle between Comanches and Apaches had assumed legendary proportions: in 1784, in recounting the history of the southern Plains, Texas governor Domingo Cabello y Robles recorded that some 60 years earlier (i.e., c. 1724) the Apaches had been routed from the southern Plains in a nine-day battle at La Gran Sierra del Fierro ‘The Great Mountain of Iron’, somewhere northwest of Texas.

The Kʉhtsʉtʉhka (Kotsoteka) ('Buffalo Eaters'), which had moved southeast in the 1750s and 1760s to the Southern Plains in Texas, were called Cuchanec Orientales ("Eastern Cuchanec/Kotsoteka") or Eastern Comanche, while those Kʉhtsʉtʉhka (Kotsoteka) that remained in the northwest and west, together with Hʉpenʉʉ (Jupe, Hoipi – 'Timber/Forest People') (and sometimes Yaparʉhka (Yamparika)), which had moved southward to the North Canadian River, were called Cuchanec Occidentales ("Western Cuchanec/Kotsoteka") or Western Comanche.

The "Eastern Comanche" lived on the Edwards Plateau and the Texas plains of the upper Brazos and Colorado Rivers, and east to the Cross Timbers.

The latter originally some local groups of the Kʉhtsʉtʉhka (Kotsoteka) from the Cimarron River Valley as well as descendants of some Hʉpenʉʉ (Jupe, Hoipi), which had pulled both southwards.

With them shared two smaller bands the same tribal areas: the Tahnahwah (Tenawa, Tenahwit) ("Those Living Downstream") and Tanimʉʉ (Tanima, Dahaʉi, Tevawish) ("Liver Eaters").

The "Western Comanche" label encompassed the Kwaarʉ Nʉʉ (Kwahadi, Quohada) ('Antelope Eaters'), which is the last to develop as an independent band in the 19th century.

However, the massive population of the settlers from the east and the diseases they brought led to pressure and decline of Comanche power and the cessation of their major presence in the southern Great Plains.

[32][33][34][35] Similarly, they were, at one time or another, at war with virtually every other Native American group living on the South Plains,[36][37] leaving opportunities for political maneuvering by European colonial powers and the United States.

While the Comanche managed to maintain their independence and increase their territory, by the mid-19th century, they faced annihilation because of a wave of epidemics due to Eurasian diseases to which they had no immunity, such as smallpox and measles.

The US began efforts in the late 1860s to move the Comanche into reservations, with the Treaty of Medicine Lodge (1867), which offered churches, schools, and annuities in return for a vast tract of land totaling over 60,000 square miles (160,000 km2).

The government promised to stop the buffalo hunters, who were decimating the great herds of the Plains, provided that the Comanche, along with the Apaches, Kiowas, Cheyenne, and Arapahos, move to a reservation totaling less than 5,000 square miles (13,000 km2) of land.

The Comanche under Quenatosavit White Eagle (later called Isa-tai "Coyote's Vagina") retaliated by attacking a group of hunters in the Texas Panhandle in the Second Battle of Adobe Walls (1874).

In May 1875, the last free band of Comanches, led by the Quahada warrior Quanah Parker, surrendered and moved to the Fort Sill reservation in Oklahoma.

Petri's sketches and watercolors gave witness to the friendly relationships between the Germans and various local Native American tribes.

[48]During World War II, many Comanche left the traditional tribal lands in Oklahoma to seek jobs and more opportunities in the cities of California and the Southwest.

They carried water and collected wood, and at about 12 years old learned to cook meals, make tipis, sew clothing, prepare hides, and perform other tasks essential to becoming a wife and mother.

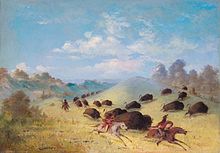

Often horse herds numbering in the hundreds were stolen by Comanche during raids against other Indian nations, Spanish, Mexicans, and later from the ranches of Texans.

To prepare the hides, women spread them on the ground, scraped off the fat and flesh with blades of bone or antler, and dried them in the sun.

Two wing-shaped flaps at the top of the tipi were turned back to make an opening, which could be adjusted to keep out moisture and held pockets of insulating air.

When they lived in the Rocky Mountains, during their migration to the Great Plains, both men and women shared responsibility for gathering and providing food.

To boil fresh or dried meat and vegetables, women dug a pit in the ground, which they lined with animal skins or bison stomach and filled with water to make a kind of cooking pot.

They prepared meals whenever a visitor arrived in camp, which led to outsiders' belief that the Comanches ate at all hours of the day or night.

[64] Comanche men usually had pierced ears with hanging earrings made of pieces of shell or loops of brass or silver wire.

With wood scarce on the plains, women relied on buffalo chips (dried dung) as fuel for cooking and heat.

Scraped to resemble white parchment, rawhide skins were folded to make parfleches in which food, clothing, and other personal belongings were kept.

Women also tanned hides to make soft and supple buckskin, which was used for tipi covers, warm robes, blankets, cloths, and moccasins.

[71] During World War II, a group of 17 young men, referred to as "the Comanche code talkers", were trained and used by the U.S. Army to send messages conveying sensitive information that could not be deciphered by the Germans.