Kražiai massacre

As part of wider Russification efforts, the Tsarist government decided to close the women's Benedictine monastery in Kražiai.

71 persons were put on trial for rioting and disobeying police orders, but the cruelty of the Cossacks caused a public outcry and the people received a pardon from the Tsar.

In response to the failed uprisings in 1831 and 1863–1864, Tsarist authorities enacted various Russification policies, including the Lithuanian press ban and various restrictions on the Roman Catholic Church.

[10] Governor-General Ivan Kakhanov [ru] investigated the issue and recommended to the Ministry of the Interior of the Russian Empire to transfer the churches.

However, on 1 January 1893, Kakhanov who was implicated in a corruption scandal (accused of misappropriating funds collected for a monument to Mikhail Muravyov-Vilensky) was replaced by Pyotr Orzhevsky [ru], former commander of the Special Corps of Gendarmes.

[9] Orzhevsky was a strong supporter of the various Russification policies and perhaps hoped that his strict stance would gain him favor in Saint Petersburg and restart his political career.

[11] The Benedictine nuns attempted to delay their move to Kaunas using various excuses, including lack of warm clothing and ill health.

Due to poor health, Aleksandra Sieliniewska, Benedykta Choromańska, Salomea Siemaszkówna, and Abbess Michalina Paniewska remained in Kražiai.

[11] The residents sent letters not only to the central Russian authorities but also to the governments of foreign countries: Austria-Hungary, Germany, Italy, France, the United Kingdom, USA, and Denmark.

Activists of the Lithuanian national revival, particularly those associated with the journal Žemaičių ir Lietuvos apžvalga, which had been published since 1890 in Tilsit, also became involved in the defense of the church.

Chief of the Raseiniai Uyezd was beaten and almost hanged, but freed by the Russian policemen, while Klingenberg barricaded himself in a church choir balcony.

The priests were forbidden from recording the names of the victims and performing funeral rites, including sprinkling the ground with holy water.

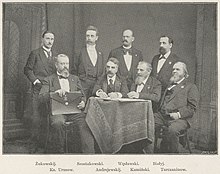

[16] In total, 330 people were interrogated and 71 (34 peasants, 27 nobles, and 10 city residents; 55 men and 16 women)[2] were arrested and put on trial in Vilnius.

[3] The press attacked the popular notion of "good Tsar, bad bureaucrats" and praised Kražiai defenders as martyrs and an inspirational example for others to follow.

The events caused a stir among Lithuanian Americans who collected donations, held lectures, and organized protest rallies.

[3] In March 1894, Pope Leo XIII issued encyclical Caritatis on the church in Poland sparking a fierce debate between Catholic and secular Lithuanian activists.

Vincas Kudirka in Varpas attacked the encyclical because the pope urged compliance and obedience to the Tsarist regime and thus "betrayed the blood spilled in Kražiai".

[20] Defenders of the encyclical, including Pranciškus Bučys, pointed out that it forced Tsarist authorities to make concessions and relax restrictions on the Catholic Church and that the pope urged obedience only as much as it did not go against religious beliefs and freedom.

[10] After the debate, most of the clergy withdrew their support to Varpas and instead focused on Catholic Žemaičių ir Lietuvos apžvalga and Tėvynės sargas.

At the time, the authoritarian regime of Antanas Smetona attempted to lessen the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and thus weaken its main opponent, the Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party.

The union encouraged people to follow the example of Kražiai defenders and continue to fight for the Vilnius Region disputed with the Second Polish Republic.

There were other plans for commemorating the events with special medals, monument, or enlarged museum all aimed at the anticipated grand ceremony in 1943, the 50th anniversary.