Kresy

Historically situated in the eastern Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, following the 18th-century foreign partitions it was divided between the Empires of Russia and Austria-Hungary, and ceded to Poland in 1921 after the Treaty of Riga.

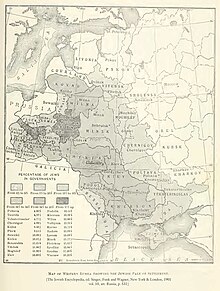

[4] Kresy is also largely co-terminous with the northern areas of the Pale of Settlement, a scheme devised by Catherine II of Russia to limit Jews from settling in the homogenously Christian Orthodox core of the Russian Empire, such as Moscow and Saint Petersburg.

[5] Administratively, the Eastern Borderlands territory was composed of Lwów, Nowogródek, Polesie, Stanisławów, Tarnopol, Wilno, Wołyń, and Białystok voivodeships (provinces).

According to Zbigniew Gołąb, it is "a medieval borrowing from the German word Kreis", which in the Middle Ages meant Kreislinie, Umkreis, Landeskreis ("borderline, delineation or circumscribed territory").

Moreover, the indigenous upper classes of Kresy accepted Polish religion, culture and language, resulting in their assimilation and Polonization.

It also comprised about 20% of the territory of European Russia and largely corresponded to historical lands of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Cossack Hetmanate, and the Ottoman Empire (with Crimean Khanate).

[11] The Russian Empire had abandoned Kresy to decline as a vast rural backwater after the original Polish–Lithuanian landowners had been disposed of in the wake of insurrections and the Abolition of serfdom in Poland in 1864.

By the time of a newly resurgent Polish state, the provinces had been additionally disadvantaged by having the lowest literacy levels in the country, since education had not been compulsory during Russian rule.

[12][13][14] The regions had suffered a legacy of decades of neglect and underinvestment so were generally less economically developed than the western parts of interwar Poland.

After the German invasion of the USSR, the southeastern part of Kresy was absorbed into Greater Germany's General Government, whereas the rest was integrated with the Reichskommissariats Ostland and Ukraine.

During the Tehran Conference in 1943, a new Soviet-Polish border was established, in effect sanctioning most of the Soviet territorial acquisitions of September 1939 (except for some areas around Białystok and Przemyśl), ignoring protests from the Polish government-in-exile in London.

Poles from the southern Kresy (now Ukraine) were forced to settle mainly in Silesia, while those from the north (Belarus and Lithuania) moved to Pomerania and Masuria.

[21] In 1948, people born in the Eastern Borderlands made up 47.5% of the population of Opole, 44.7% of Baborów, 47.5% of Wołczyn, 42.1% of Głubczyce, 40.1% of Lewin Brzeski, and 32.6% of Brzeg.

[22] The town of Jasień was settled by people from the area of Ternopil in late 1945 and early 1946,[23] while Poles from Borschiv moved to Trzcińsko-Zdrój and Chojna.

[25] Altogether, between 1944 and 1946, more than a million Poles from the Kresy were moved to the Recovered Territories, including 150,000 from the area of Wilno, 226,300 from Polesia, 133,900 from Volhynia, 5,000 from Northern Bukovina, and 618,200 from Eastern Galicia.

Eastern settlers did not feel at home in Lower Silesia, and as a result, they did not care about the machinery, households and farms abandoned by Germans.

Zdzisław Mach, a sociologist from the Jagiellonian University, explains that when Poles were forced to resettle in the West, which they resented, they had to leave the land they considered sacred and move to areas inhabited by the enemy.

In addition, Communist authorities did not initially invest in the Recovered Territories because, like the settlers, for a long time they were unsure about the future of these lands.

Other national minorities included Lithuanians and Karaites (in the north), Jews (scattered in cities and towns across the area), Czechs and Germans (in Volhynia and East Galicia), Armenians and Hungarians (in Lviv) and also Russians and Tatars.

Polish population east of the Curzon Line before World War II can be estimated by adding together figures for Former Eastern Poland and for pre-1939 Soviet Union:

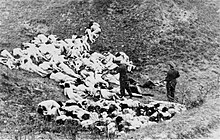

[50] The mother of Bogdan Zdrojewski, Minister of Culture and National Heritage is from Boryslav,[51] and the father of former First Lady Jolanta Kwaśniewska was born in Wołyń, where his sister was murdered in 1943 by the Ukrainian nationalists.

[53] One of the exceptions was the immensely popular comedy trilogy by Sylwester Chęciński (Sami swoi from 1967, Nie ma mocnych from 1974, and Kochaj albo rzuć from 1977).

The trilogy tells the story of two quarreling families, who after the end of the Second World War were resettled from current Western Ukraine to Lower Silesia, after Poland was shifted westwards.

Examples of such publications include: In the first half of 2011, Rzeczpospolita daily published a series called "The Book of Eastern Borderlands" (Księga kresów wschodnich).

[58] The July 2012 issue of the Uważam Rze Historia magazine was dedicated to the Eastern Borderlands and their importance in Polish history and culture.

[68] Even though Poland lost its Eastern Borderlands in the aftermath of World War II, Poles connected with the Kresy still have some affection for those lands.

There are numerous Kresy-oriented organizations, with the largest one, World Congress of Kresy Inhabitants (Światowy Kongres Kresowian), located in Bytom, and branches scattered across Poland, and abroad.

[78] Participants of annual Katyń Motorcycle Raid (Motocyklowy Rajd Katyński) always visit Polish centers in Kresy, giving presents to children, and meeting local Poles.

[83] Before World War II, the Kresy provinces were part of Poland, and both dialects were in common usage, spoken by millions of ethnic Poles.

After the war and Soviet annexation of Kresy, however, the majority of ethnic Poles were deported westward, resulting in a severe decline in the number of native speakers.