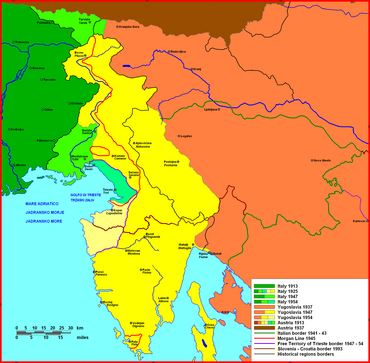

Italian irredentism in Istria

Following 1815, Istria became a part of the Austrian monarchy, and Croats, Slovenians and Italians engaged in a nationalistic feud with each other.

In response to these, the anti-Italian nationalist organisation TIGR (a Slovene acronym for Trieste (Trst), Istria (Istra), Gorizia (Gorica) and Rijeka (Reka).)

[9][10] After Napoleon the idea of "unification" of all the Italian people in a "united Italy" started to be developed by intellectuals like the Istrian Carlo Combi.

The main representatives of these ideas in historical writings are Pacifico Valussi and the Istrians Carlo Combi, Tommaso Luciani and Sigismondo Bonfiglio.

Opinion about the Slavs had entirely changed: they were seen as peasant folk unable to build a nation of their own and therefore condemned to be assimilated within an Italian identity.

[13] During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanisation or Slavicisation of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[14] His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard.

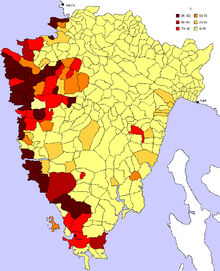

His Majesty calls the central offices to the strong duty to proceed in this way to what has been established.This created a huge wave of emigration of Italians from Istria before World War I, reducing their percentage inside the peninsula inhabitants (they were more than 50% of the total population for centuries,[17] but at the end of the 19th century they were reduced to only two fifth according to some estimates).

Indeed, in 1910, the ethnic and linguistic composition was completely mixed and the Italians were reduced to a minority in the Austrian province of Istria (even if huge).

In the second half of the 19th century, a clash of new ideological movements, Italian irredentism (which claimed Trieste and Istria) and Slovene and Croatian nationalism (developing individual identities in some quarters whilst seeking to unite in a South Slavic bid in others), resulted in growing ethnic conflict between Italians one side and Slovenes and Croats in opposition.

This was intertwined with the class and religious conflict, as inhabitants of towns and western agricultural lands were mostly Italian, whilst Croats or Slovenes largely lived out in the countryside and elsewhere.

In 1897 Matteo Bartoli, a linguist from Rovigno, pinpointed that 20,000 names were changed with this forgery, mainly in eastern Istria and even in some Dalmatian islands.

Tino Gavardo, Pio Riego Gambini and Nazario Sauro where the most renowned between those who promoted the Istrian unification to Italy.